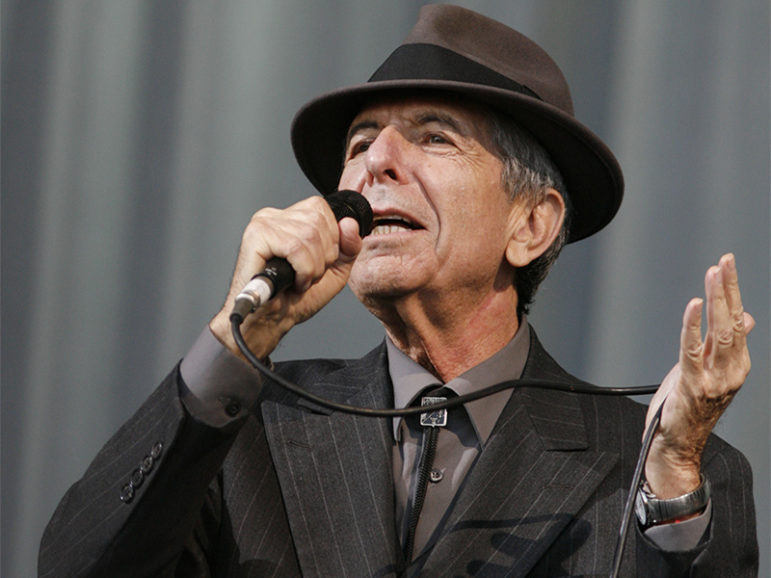

(RNS) Leonard Cohen — novelist, poet, singer, songwriter — has died at the age of 82.

Cohen, whose death earlier this week was made public on Thursday (Nov. 10), was the quintessential Jewish composer of our time — yes, perhaps, even more than Bob Dylan.

Cohen was not only an entertainer (the word seems so inadequate).

He was a rabbi, a teacher — with his own unique Torah.

First, Cohen taught us how to be simultaneously worldly and Jewish.

For that was what Cohen was: deeply Jewish — even when he included Christian images in his songs; even when he lived as a Buddhist monk.

He was a product of Jewish Montreal — Cohen’s family members were leaders in the Montreal Jewish community. His grandfather was a noted rabbi and scholar.

The names of his books — “Book of Mercy,” “Book of Longing” — sound Jewish, as if they were sacred works, in the tradition of the Psalms. He wrote liturgical poetry that became songs — some of which, like “Who By Fire,” and the ubiquitous “Hallelujah,” have become staples of contemporary synagogue music.

Cohen was that rarity among Jewish pop stars — an unapologetic Zionist. During the Yom Kippur War, he traveled to Israel to entertain the Israel Defense Forces.

In 2009, he gave a concert in Ramat Gan.

He spoke to the audience in Hebrew.

He opened the show with the first sentence of the Jewish prayer Ma Tovu — “How goodly are your tents, O Jacob …”

He ended the concert with the priestly blessing — obviously aware that as a Cohen, a descendant of the priestly class, it was, in fact, his prerogative.

Second, Cohen embodied the prophetic impulse of Judaism.

In December 1963, in a symposium on the future of Judaism in Canada, Cohen gave an address, “Loneliness and History.”

In that speech, he castigated the Montreal Jewish community for abandoning the spiritual for the material. He delivered a full-throated assault on the religious emptiness of the community, and the smugness of those who sat in the pews.

They did not realize their blood was consecrated…They did not seem to realize how fragile the ceremony was. They participated in it blindly, as if it would last forever…Their nobility was insecure because it rested on inheritance and not moment-to-moment creation in the face of annihilation…

The beautiful melody soared, which proclaimed that the Law was a tree of life and a path of peace. Couldn’t they see how it had to be nourished?

And, he concluded:

“Jews were afraid to be lonely. Jews must survive in their loneliness as witnesses. Jews are the witnesses to monotheism and that is what they must continue to declare.”

It was as if he was channeling Amos or Isaiah.

And finally, Cohen taught us how to confront death.

I knew that this day was coming.

We all did, even if we were in denial — thinking that an 82-year-old rock star could go on forever, ignoring the fact that he was already three times as old as Jim Morrison, Jimi Hendrix, Janis Joplin, Brian Jones, Kurt Cobain, and Amy Winehouse were when the Angel of Death invited each one of them to jam.

Cohen had no illusions. Not since the late Warren Zevon sang about his own impending death from cancer (“Please Stay“) has a popular musician so powerfully confronted his or her own mortality.

I am referring, of course, to his final album, “You Want It Darker,” which was released just weeks ago. In the title track, he recited his own interpretation of Kaddish, the traditional prayer for the dead — with the refrain: “Hineini (here I am) — I’m ready, my Lord.”

Not long before that, Cohen’s old lover-muse, Marianne Ihlen, died — the subject of his classic song, “So Long, Marianne.”

In a letter to her, written shortly before her death, Cohen wrote:

Well Marianne it’s come to this time when we are really so old and our bodies are falling apart and I think I will follow you very soon. Know that I am so close behind you that if you stretch out your hand, I think you can reach mine.

And you know that I’ve always loved you for your beauty and your wisdom, but I don’t need to say anything more about that because you know all about that. But now, I just want to wish you a very good journey. Goodbye old friend. Endless love, see you down the road.

Wow. One holy wow.

Imagine what it would be like to confront death that way.

I would like to think that right about now, Cohen is singing to God (from “If It Be Your Will”):

If it be your will

That I speak no more

And my voice be still

As it was before

I will speak no more

I shall abide until

I am spoken for

If it be your will.

May Leonard Cohen’s memory be an eternal blessing.