“Jeanne d’Arc écoutant les voix” by Eugene Thirion in 1876 depicts Joan of Arc’s awe upon receiving a vision from the Archangel Michael. Image courtesy of Creative Commons

CHICAGO (RNS) She was young, illiterate and had power for less than two years. History — seldom interested in women and usually written by the triumphant — should have forgotten her.

But when she died on a pyre in 1431, she achieved an immortality in art and literature that surpasses all of her contemporaries — kings, popes, knights, priests and courtiers.

She, of course, is Joan of Arc, the French teenage country girl who, through her extreme faith, mystic visions and what must have been an astonishing amount of personal charisma, led French troops to a string of glorious victories against the invading English. She was eventually captured and tried for heresy. Her remains were tossed in a river, like so much trash.

[ad number=“1”]

While Joan has never entirely dropped out of the public imagination — the first poem about her appeared in 1429 — she is experiencing a revival. The past year saw a major production of George Bernard Shaw’s “Saint Joan” in London, a new musical based on her life in New York and a film about her childhood that premiered at the Cannes Film Festival. A new, critically-acclaimed novel, “The Book of Joan,” takes her story into a sci-fi future.

“I shall last a year and but a little longer,” by Susan Aurinko. Image courtesy of Susan Aurinko

Now, a new photography show at the Loyola University Museum of Art tries to recapture something of the real Joan — or “Jehanne,” as she signed her name. Called “Searching for Jehanne — The Joan of Arc Project,” it features 37 elaborately framed photographs by Chicago-based artist Susan Aurinko.

And while scores of creative types have crafted all sorts of ideas of Joan (for Shakespeare she was a witch, for Bertolt Brecht she was a labor leader, and CBS made her a contemporary teen in “Joan of Arcadia”), Aurinko has her own version, drawn from Joan’s actual words and the places she lived, fought and died.

“I was not trying to solve the mystery of Joan; I was trying to give it dimension,” Aurinko said from her spacious work-live loft west of downtown Chicago, her photographs arranged around her, awaiting their trip to the museum. “I wanted to allow her to speak now in a way that makes her a little more real to people.”

Aurinko hopes her photographs will connect the viewer to what she considers essential about Joan — her faith, her strength and her sense of her own destiny.

Joan of Arc

Joan was born in the small French village of Domrémy-la-Pucelle in 1412 in the middle of the Hundred Years’ War, a clash between France and England over the French throne. Her parents were farmers and loyal to Charles of Valois, the French dauphin, or prince.

Joan had her first vision when she was 12, claiming Saints Michael, Catherine and Margaret told her she should drive out the English and see Charles enthroned.

[ad number=“2”]

“‘Daughter of God, go on, go on, go on! I will be your help. Go on!,'” she is supposed to have said of her visions. “When I hear this voice, I feel such great joy that I wish I could always hear it!”

At 16, she made her way to Charles’ supporters and convinced them to give her a pair of men’s armor. She cut her hair and led a band of followers to Charles.

“I was born for this,” she was reported to say. “I must be with the dauphin, even if I have to wear my legs down to my knees.”

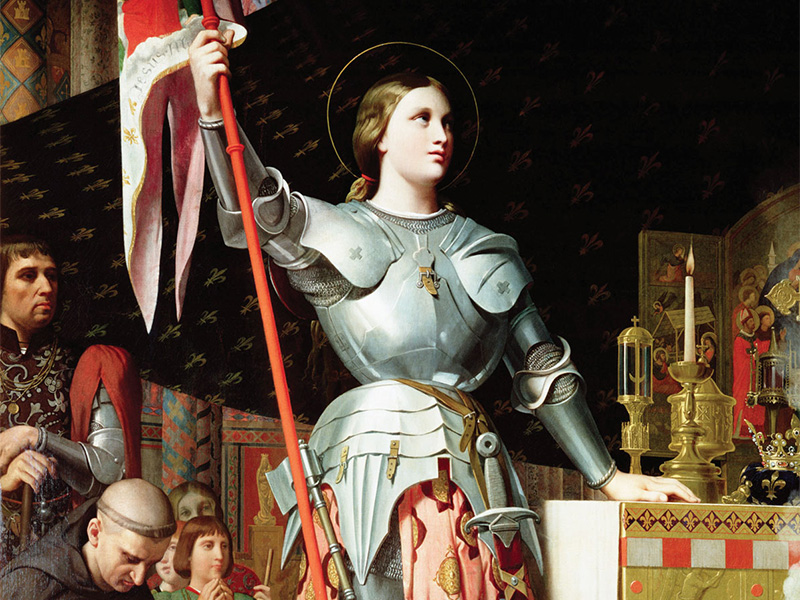

“Joan at the coronation of Charles VII,” by Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres in 1854, a famous painting often reproduced in works on Joan of Arc. Image courtesy of Creative Commons

Joan whispered something in Charles’ ear — perhaps a prophesy, perhaps a promise, that he would be king. Whatever she said, it worked. He gave her an army, which she led to Orleans and lifted the English siege.

The victory made Joan as famous as Charles himself. She saw him crowned Charles VII in 1429.

But in 1430, Joan’s fortunes fell. While defending a town outside Paris, she was wounded, thrown from her horse and captured by English allies. She was imprisoned in a tower in Rouen and tried for witchcraft and heresy.

She proved such a match for her prosecutors that Shaw used some of her testimony verbatim in his play. Asked if she knew she was in God’s grace — a trap, since to be certain of grace was heresy — she replied, “If I am not, may God put me there; and if I am, may God so keep me.”

They burned her anyway. She was 19 years old.

In the late 1800s, transcripts of Joan’s lengthy trial resurfaced and a push for sainthood undertaken. She was beatified in 1905 and canonized in 1920 — and the intervening years saw Joan reborn on the stage, on the page and beyond.

Joan of art

Joan of Arc WWI Poster from the United States by Haskell Coffin, c. 1914-1918.

Joan was painted by Rubens, Ingres and Gaugin, written into music by Tchaikovsky, Leonard Bernstein, Madonna and Cradle of Filth. Martha Graham danced her, Hedy Lamarr played her on the screen, and Mark Twain, Terry Pratchett, Thomas Keneally and Mary Gordon wrote books about her.

Joan entered the political realm, too. During World War I, her image adorned posters, stamps and war bonds to rally support for the Allies, even beyond France.

“Joan of Arc saved France,” a 1918 U.S. Department of the Treasury poster reads. “Women of America, save your country: Buy war savings stamps.”

Every French presidential candidate, from Charles de Gaulle to Marine LePen, has evoked the name of Joan of Arc on the campaign trail.

Her image has sold magazines, cans of beans, blocks of cheese, and tickets to the circus. An old postcard shows a Joan saying, “Remember kids, Joan of Arc says: ‘Please don’t smoke!'”

An advertisement for Joan of Arc beans in the United States in 1964.

What about this once obscure teenage girl speaks across centuries, crosses boundaries of art and consumerism as well as those of faith, culture and language?

David Clayton, who oversees a new masters in sacred art at Pontifex University, said that as a Catholic, he cannot separate Joan from her faith. He sees it as crucial to her enduring appeal among artists like himself.

“Joan’s story shows the power of the grace of God,” he said. “There is something immensely hopeful about this figure who is young, female and fighting in a man’s world. It is a story that speaks to all of us of our own salvation story.”

“Joan of Arc: Into the Fire” play poster. Image courtesy of the Public Theater

Kathryn Harrison explored Joan’s allure in “Joan of Arc: A Life Transfigured.” Asked what drew her — an acclaimed novelist and memoirist to produce a Joan biography — she said in an email, “once I’d heard that voice, centuries old, translated through time and culture and language, and ‘watched’ as she nimbly outwitted scores of church doctors bent on executing her, I was in love forever.”

Joan’s story she concluded, defies explanation. Was she a mystic or a fraud? Was she divinely inspired or delusional?

“We don’t need narratives that rationalize human experience so much as those that enlarge it with the breath of mystery,” Harrison wrote in The New York Times. “For as long as we look to heroes for inspiration, to leaders whose vision lifts them above our limited perspective, who cherish their values above their earthly lives, the story of Joan of Arc will remain one we remember, and celebrate.”

Ann Astell, a professor of Christian history at the University of Notre Dame and the author of “Joan of Arc and Sacrificial Authorship,” has studied Joan’s pull on artists.

[ad number=“3”]

“They see her as someone beautiful and inspired, a person of of genius, but also vulnerable, because of that very giftedness, to misunderstanding, vilification, trial, and rejection by the public,” Astell said in an email. “In her final triumph over death, her recognition as a saint and martyr, they find hope that others will someday recognize the beauty of their own art and the truth of their calling.”

Joan of Chicago

“When I was thirteen, I heard a voice from God to help me govern myself,” by Susan Aurinko. Image courtesy of Susan Aurinko

Aurinko was blindsided by Joan while on a 2013 European vacation with a friend. Alone with her camera in a tower in France’s Chateau de Chinon, where Joan petitioned Charles for an army, she was stirred by the sunlight drifting through arrow slits in the wall and the sudden sound of many footsteps on the stone stairs.

When she looked, there was no one. Just her, the light and her camera.

Artist Susan Aurinko. Photo courtesy of Susan Aurinko

“It was a photographer’s paradise,” she said. “I was in heaven.”

She had no idea of the chateau’s association with Joan until she hit its gift store and saw books about Joan.

“I had been shooting the places she walked,” she said. “It was remarkable to be in a room she slept in, she dreamed in.”

She couldn’t shake the fascination and began searching for images of Joan on the internet.

“There were thousands,” she said. “I think that is when the project came to my mind, when I realized we have no idea what she looked like.”

Aurinko made three more trips to France and visited every Joan-related site she could find. She hired models to portray Joan at different ages in a few of the photos and shot every Joan statue she came across, trying to evoke an essence of a girl. She pored over Joan’s court testimony and incorporated her words into the photographs.

Back in the studio, Aurinko layered the images, superimposing statuary and models on empty staircases, in church sanctuaries, on castle walls. Everything is bathed in light — Joan said bright light accompanied the voices in her visions — and steeped in a warm palette of amber, gold, burnt sienna and wheat.

“I promise and declare that I will not abandon you as long as I live,” by Susan Aurinko. Image courtesy of Susan Aurinko

“I was molding my own Joan,” Aurinko said. “I thought of her in three ways — Joan the warrior, Joan the maid, and Joan the child. It is very important people understand her sweetness and vulnerability. She was not this big-shouldered warrior girl. She was a child when she died and was as confused by those voices as anyone who heard about them.”

Aurinko’s Joan in these images is a girl caught in time — but which time? There she is cut in stone, a medieval maiden; there she is cast in bronze, the Victorian ideal of a woman at prayer; there she is depicted by a model as a girl who might have just walked out of the local high school — in a full coat of mail.

Aurinko had no connection to Catholicism before encountering Joan. She was raised in the Congregational tradition, but converted to Judaism in her 20s.

“Where all this fascination with Catholicism is coming from, I have no idea,” she said with a laugh and wave of her hands. “But it extends beyond Joan. I have always been interested in spirituality, to people’s relationship to their higher power. And Joan, clearly, had a very deep connection with her higher power.”