Pennsylvania Attorney General Josh Shapiro speaks during a news conference at the state Capitol in Harrisburg, Pa., on Aug. 14, 2018. A Pennsylvania grand jury’s investigation of clergy sexual abuse identified more than 1,000 child victims. The people seated were some of those affected by the clergy abuse. (AP Photo/Matt Rourke)

(RNS) — “Our work in Pennsylvania has spurred a movement,” Josh Shapiro, the state’s attorney general, said earlier this month as New York and New Jersey announced they would, like Pennsylvania, investigate child sexual abuse in Catholic dioceses within their borders.

Since Shapiro unveiled a grand jury report in August detailing decades of allegations of child sex abuse by Catholic priests, at least nine states have initiated some form of investigation of their own. The issue also continues to rage in Pennsylvania courts: On Monday, parents of children in the Roman Catholic Church and survivors of sexual abuse sued eight dioceses and their bishops to compel them to release more information regarding allegations.

But as new investigations begin, questions remain as to what exactly will be revealed, and how much of it will result in legal action.

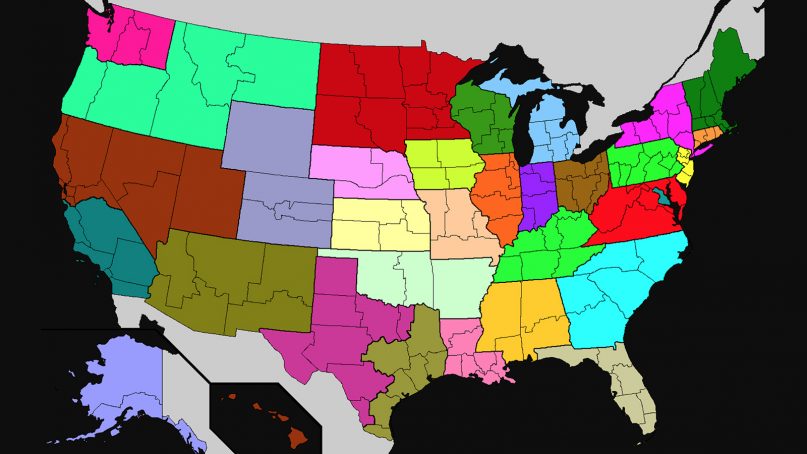

A Religion News Service survey of 178 Roman Catholic dioceses and archdioceses in the U.S. (excluding those in Pennsylvania) suggests many internal church documents of the kind that yielded the staggering history of abuse in Pennsylvania have already been examined by law enforcement in other states after The Boston Globe’s “Spotlight” investigation in the early 2000s.

A map of the Roman Catholic ecclesiastical provinces of the United States. Each province is a separate color, with outlines of individual archdioceses and dioceses. Map courtesy of Creative Commons

Experts also say that in many dioceses communications between law enforcement and the church have continued.

“It’s not a ‘gotcha game,’ and I don’t think the church looks at it that way,” said Kathleen McChesney, a former FBI executive assistant director who worked with the Catholic Church’s National Review Board in the aftermath of the Spotlight scandal.

McChesney said many dioceses recognize that involving law enforcement is “a very positive step” and that the church’s response to inquiries prompted by the Pennsylvania grand jury report won’t look much different from a probe of a corporation.

McChesney voiced frustration that officials hadn’t acted sooner: “Had law enforcement been more engaged 15 years ago, that would have been helpful.”

At least 24 of the 91 Roman Catholic dioceses that responded to RNS’ survey claimed their files were inspected by authorities in years past, either during a formal investigation or during bankruptcy proceedings, often resulting from a costly settlement of a child abuse case.

Others said they have made some or even all their files regarding accused priests public, posted the names of those accused on their website or launched independent investigations of their own files using law firms.

Besides those investigated in Pennsylvania and two Missouri dioceses that have already offered to share their files, more than 40 said they would cooperate with law enforcement if asked.

Still others are following the example of the Archdiocese of St. Louis, which recently invited Missouri Attorney General Josh Hawley to review all of its internal files regarding allegations of abuse by priests.

“Right now, we are reviewing our files to make sure we have turned over everything pertinent to cases reported since 2002,” read a statement sent to RNS from the Diocese of Jackson, Miss., which also said its files were reviewed in 2002. “Bishop (Joseph) Kopacz wants to offer the current Attorney General the opportunity to review those files even though they have already been submitted to the District Attorneys who would have direct jurisdiction over the allegations.”

Still, changes in state law could offer abuse victims the ability to file civil cases where statutes of limitations on criminal activity have run out.

Kathleen McChesney. Photo courtesy of Kathleen McChesney

“Some states have lifted the statute of limitations,” McChesney said, pointing to Minnesota and California. “While that didn’t bring forth criminal action against the perpetrators, it brought civil action against the dioceses or the religious community that was involved in it. So information that comes from these law enforcement inquiries could be used, ostensibly, in potential civil cases.”

McChesney was quick to note that church procedures guarding against child sex abuse have been updated and strengthened in the years since the Spotlight era. She predicted that many allegations uncovered by new investigations will likely fall outside the statute of limitations.

But Tim Lennon, president of the Survivors Network of those Abused by Priests, or SNAP, said ongoing investigations may not go far enough to satisfy many abuse victims — or uncover the full truth.

“We want something that’s independent, something that has subpoena power, and something where testimony is compelled under oath,” he said. “Pennsylvania demonstrated that the church is not honest.”

By way of example, he said that prior to the Pennsylvania grand jury report, SNAP was only aware of 10 alleged abusers in the Diocese of Harrisburg. But that number grew to more than 70 when the diocese released a list of names in August ahead of the report’s unveiling.

Lennon also insisted that even among dioceses where documents have been released during bankruptcy proceedings, more transparency is needed.

At least 19 Catholic dioceses and religious orders in the United States have filed for bankruptcy protection over the past 14 years because of the clergy sexual abuse crisis, according to watchdog group Bishop-accountability.org. In May, the Archdiocese of St. Paul-Minneapolis reached a $210 million settlement — which lawyers called the largest of its kind in history — in a bankruptcy case that followed several clergy abuse lawsuits.

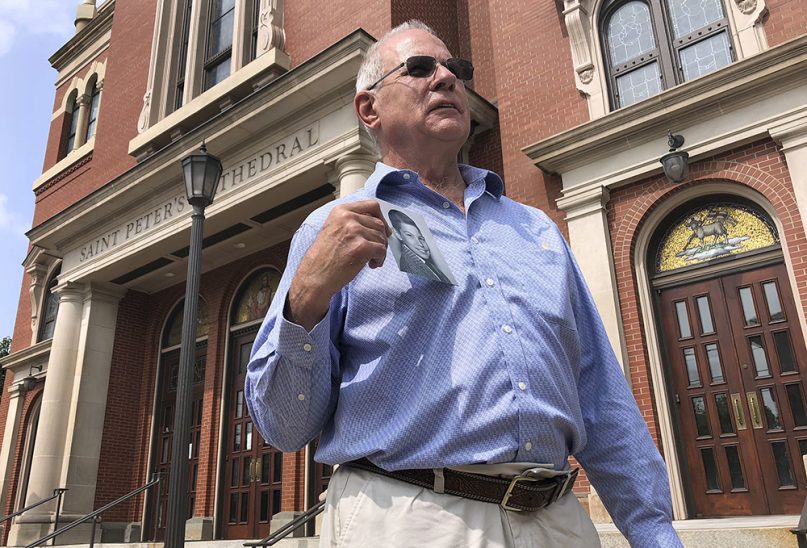

Tim Lennon, president of SNAP, holds a photo of himself as a young boy, in front of the Cathedral of St. Peter in Scranton, Pa., on Aug. 20, 2018. Lennon said his organization has fielded calls from Catholics who have pledged to stop giving to their church. (AP Photo/Michael Rubinkam)

Jeff Anderson, who represented the St. Paul-Minneapolis victims, said attorneys like him have known of the existence of files on abuse allegations and have been “excavating them since the ’80s with limited success.” Church officials can use bankruptcy proceedings “as a shield and a sword,” he said, to halt ongoing litigation and keep documents from exposure.

“Bankruptcy is a way for the church to control the information,” SNAP’s Lennon said. “It’s not shared — it’s controlled by the church.”

Lennon said he and SNAP are now calling for all 50 states to launch robust investigations, as well as the federal government. (Shapiro has said that a “senior official at the Department of Justice” reached out to him after he unveiled the grand jury report; the agency declined to comment on whether it is preparing to investigate.)

Nor is Lennon satisfied with the penitence the church has shown in Pennsylvania and elsewhere since the grand jury’s report was released. Posting the names of accused priests on websites and removing the names of bishops from buildings may be a form of progress, Lennon said, but such gestures won’t answer victims’ desires for “some form of restorative justice.”

“What they need to do is the next step, which is sell the buildings and help the survivors,” he said.

(Emily Miller contributed to this report.)