Emily Jensen

A guest post by Emily Jensen

In the Saturday night priesthood session of General Conference, Dallin H. Oaks of the First Presidency of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints made this comment about race being an unimportant “label” in the eyes of God:

“‘Where will this lead?’ is also important in choosing how we label or think of ourselves. Most important, each of us is a child of God with a potential destiny of eternal life. Every other label, even including occupation, race, physical characteristics, or honors, is temporary or trivial in eternal terms. Don’t choose to label yourselves or think of yourselves in terms that put a limit on a goal for which you might strive.” (emphasis added)

I feel that President Oaks was wrong to say that race is a temporary or trivial label in eternal terms. While I can understand that he is teaching that labels—including race—could divide the Zion community for which we strive, we can’t simply dismiss race as trivial, particularly with our religion’s racial history.

So let me, with apologies to President Oaks, walk you through some of the Bad, Worse, and Worst reasons why this is problematic.

Bad: On its surface, his inclusion of race in his list of labels seems to say that if you use “race” as a trivial excuse or condition for your behavior, you are in danger of losing eternal blessings.

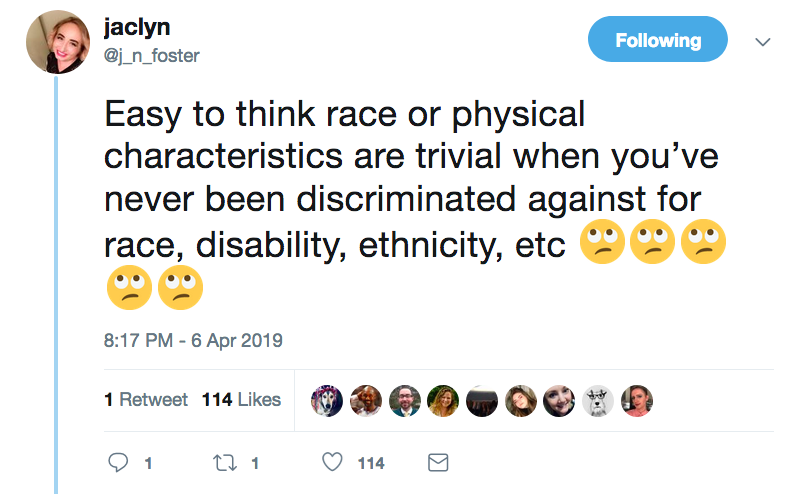

However, he is speaking from the majority here. So as tweeter Jaclyn Foster puts it so succinctly:

Claiming that race is trivial is the equivalent of saying God “doesn’t see color” so we shouldn’t worry about it either.

Worse: That little “or” is getting a lot of play in my Twitter feed, as people have taken pains to show me that President Oaks said “temporary OR trivial” and that he clearly meant that race was “trivial” and not “temporary.”

I don’t think that’s clear at all. His wording suggests he might feel that race is “temporary.” On one hand, people may feel it’s progress that a religion that once taught that race was embedded in a person’s premortal, mortal, and postmortal life—to the eternal detriment of those without white skin—is shedding that notion that race is a defining feature of a person’s eternal destiny.

On the other hand, that word “temporary” erases a part of our existence not only in the hereafter, but in mortality. For example, the church often claims that LGBT people are only temporarily non-heterosexual, and that those who live righteously will be cleansed of their queerness so they enjoy a straight (read “normal”) life in heaven. These assumptions are damaging because people may feel like a core part of their being should be erased via whatever means necessary in this life—or, worse, that if they will only become acceptable in the afterlife, they should cease to exist.

While not direct, this has parallels to race. What does President Oaks imply when he states that race is temporary? A person who is clearly speaking with authority based upon his majority status can safely ignore labels, because his (unspoken) label is his privilege. He is able to ignore labels because society allows for that safely. One cannot easily dismiss labels of race when structural racism still exists within the church, and in society.

A great read on why this is important for white people to understand interestingly comes from a few blocks from Temple Square, from inside the Utah Jazz organization. Jazz player Kyle Korver, who is not a member of the church but is cheered on by thousands of members of the church, explains what it means to be “Privileged” in Utah: “The fact that inequality is built so deeply into so many of our most trusted institutions is wrong. And I believe it’s the responsibility of anyone on the privileged end of those inequalities to help make things right.”

Worst: Our history and theology is rife with examples of leaders using race as a condition of entrance into heaven or even accepting the gospel. It swirls around the idea of the mark of Cain in the Bible and, as quoted by Sister Becky Craven on Saturday morning, self-inflicted marks delineating those who removed themselves from the righteous in the Book of Mormon. The Book of Mormon’s teaching about the superiority of white-pure and delightsome people among the Nephites entered the psyche of members to the point that President Spencer W. Kimball celebrated Native Americans becoming whiter under the Indian Placement Program. And then there’s the fact that in most LDS depictions of deity, God is white.

I’m sorry, but coming from a church which for decades refused to allow certain races access to priesthood and the temple, which in only 2019 appointed its first African American general authority, and which has still not apologized for past leaders’ statements and policies that hurt and barred black members from fully enjoying what our church has to offer, we are in no position to say that race is temporary or trivial.

But I also speak from a position of privilege and blind biases. Even as I was fuming over these words on social media, I was reminded by those saints of color who have had to have these conversations their entire lives to not tag them because they are tired of trying to teach white members to be less ignorant and more kind. Structural racism is prevalent for a reason: it’s so deeply baked into our society that many of us with white privilege just cannot see it.

Language is important. President Nelson devoted an entire General Conference talk in 2018 to the importance and meaning of the label “Mormon.” I hope that we can start important conversations about race and how it has shaped us individually and institutionally for good and bad. Most importantly, those who don’t see how President Oaks’ comments are hurtful should start listening to our fellow saints who cannot consider their race as trivial or temporary (and probably don’t want to).

After all, they’ve been in the church since the beginning. And Zion is going to be made of all of us.

Emily W. Jensen is the web editor for Dialogue: A Journal of Mormon Thought and co-editor of “A Book of Mormons: Latter-day Saints on a Modern-Day Zion.”