(RNS) — As the United Methodist Church has spent decades debating the place of LGBTQ Christians in its ministries, the Rev. Adam Hamilton has emerged as “the Pied Piper for Methodists in the middle.”

At the global denomination’s General Conference meetings in 2012 and 2016, Hamilton — who pastors the largest United Methodist church in the United States — supported measures that would have allowed United Methodists to disagree with its rulebook, which claims the “practice of homosexuality” is “incompatible” with Christian teaching.

More recently, he backed the so-called One Church Plan, which would have allowed churches and regional bodies known as annual conferences to decide whether to allow LGBTQ clergy and same-sex marriage.

RELATED: The ’Splainer: What happened at the United Methodist General Conference?

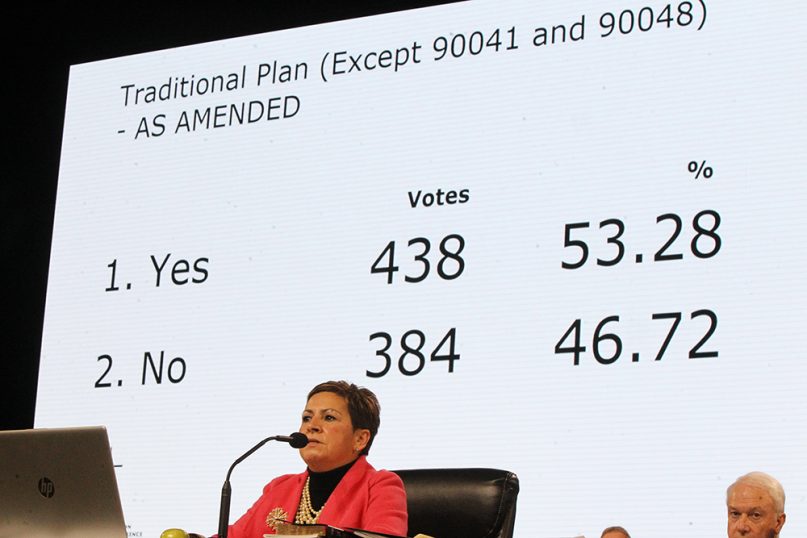

In February, that plan — which also had been recommended by the denomination’s Council of Bishops — failed at a special session of the General Conference in St. Louis. Instead, delegates adopted what’s known as the Traditional Plan, which strengthened language in the denomination’s Book of Discipline barring LGBTQ United Methodists from marriage and ministry.

The Rev. Adam Hamilton, senior pastor of Church of the Resurrection in Kansas, speaks on Feb. 26, 2019, during the special session of the General Conference of the United Methodist Church, held in St. Louis. Photo by Paul Jeffrey/UMNS

In response, Hamilton convened a meeting of more than 600 United Methodists from every annual conference in the country at the United Methodist Church of the Resurrection in Leawood, Kan., to discuss what’s next for the second-largest Protestant denomination in the U.S.

“It’s one thing if we could’ve found a way to change the policy but still leave room for people who hold different views. It’s another thing for us to not only not do that but to invoke punishments,” he said.

During the May meeting, known as UMC Next, Hamilton and others adopted four guiding principles, which include a commitment to rejecting the Traditional Plan and resisting its implementation.

Hamilton recently spoke to Religion News Service about UMC Next, how his own beliefs have evolved about what the Bible has to say to LGBTQ Christians and why he believes the United Methodist Church is worth fighting for. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

You’ve been very outspoken about your support for greater inclusivity in the United Methodist Church. Why is that?

From the time we started the Church (of the Resurrection) — so this has been 29 years — LGBT persons have come to the church.

I would say 16 or 17 years ago, my own thinking began to shift on how we read Scripture as it relates to gay and lesbian people.

United Methodist bishops and delegates gather to pray at the front of the stage before a key vote on church policies about homosexuality on Feb. 26, 2019, during the special session of the UMC General Conference in St. Louis. RNS photo by Kit Doyle

I was wrestling with the question of the Bible and how you deal with these texts that have God having the Israelites destroy 32 city-states and kill every man, woman and child. The answer that seemed most compelling to me was recognizing the role of culture and historical context in shaping the biblical authors’ values and retelling of their own history.

And so I’m wrestling with that at the time and really wrestling with what I thought I knew about LGBT persons and how God might look at them. At the time I told people: “This is a safe place for you. I’m not going to beat up on you from the pulpit. We want you here, but I believe that God’s will is that you be celibate if you can’t change.”

I was preaching a sermon right before General Conference in 2004 related to gay and lesbian people and the Methodist Church’s position on homosexuality, and I invited congregation members to share their stories. I received 200 or 300 emails, and I remember it was 1 in the morning and I’m reading them, working on my sermon and just weeping in my living room, thinking what I have always believed does not capture how I think God looks at these people whose stories I’m reading.

That led to a sermon that I preached then and that if you read it today, you wouldn’t think was really dramatic, saying that I don’t know that what I have believed about gay and lesbian people and homosexuality is accurate or right and that we are going to be a place that welcomes everybody.

Fast forward to this year’s General Conference … what nobody really anticipated was that the Traditional Plan would pass. I wasn’t certain the One Church Plan would pass, but I certainly did not anticipate the Traditional Plan passing.

Bishop Cynthia Fierro Harvey announces the results of the Traditional Plan votes late on Feb. 26, 2019. RNS photo by Kit Doyle

What’s happened since that vote? What discussions have you been part of?

What I can tell you is that there’s not a consensus yet as to exactly what needs to happen.

Some traditionalists are ready to dissolve the church and then form new expressions of Methodism. Other traditionalists I’ve talked to say, “I don’t want to dissolve the church, and I want to stay in United Methodism, but I can’t stay in the church if you’re going to be doing (same-sex) weddings somewhere else.”

There are a lot of centrists who say, “We’re ready to dissolve the church and start something new.” But there are, I believe, many, many more who would say, “I don’t want to give up on the United Methodist Church.”

RELATED: ‘In this to the end’: LGBT United Methodists express hurt, hope after vote

There are probably three major conversations that are happening that I’m aware of.

One has to do with, yes, go ahead and dissolve and create and divide the assets and create two or three new expressions of Methodism and allow every annual conference to migrate towards one or the other of those.

There’s another one that says we keep the United Methodist Church and we allow annual conferences to migrate towards one or the other of these expressions, but they remain within the United Methodist Church and they become branches within one United Methodist Church.

And another one is some people think on the traditional side, “If we make it hard enough, the centrists or progressives will leave.” And on the centrist or progressive side, there is talk like we make it hard enough, we protest enough that the traditionalists will leave.

And then finally there’s the conversation of whether centrists and progressives are able to stay together.

Some of these discussions that you mentioned about creating different branches of the church sound like the Connectional Conference Plan that was voted down at the special session. Do you think this will come up again at the 2020 General Conference in Minneapolis?

I would say they’re all variations of what that plan was attempting to do. I think that was a plan that most people weren’t really that interested in and thought it was too complicated to even pass.

But in the absence of finding any other possible solution, it may be that enough people would support that.

What will happen is over the summer time there’ll be more of these conversations happening — traditionalists and centrists and progressives; sometimes in conversation together, often in their own groups. It is possible that by 2020 General Conference there would be an agreement in principle, and then the next four years would be spent working that out.

Tell me more about UMC Next. Who was part of this meeting, and what was your takeaway?

Adam Hamilton. Photo courtesy of Church of the Resurrection

We had different voices at every table. We had LGBTQ persons who were there. We had folks who were probably center right. The one thing that they shared in common was they did not agree with the Traditional Plan and they wanted the church to be more inclusive of LGBTQ persons. I would say two-thirds of the people were centrists and a third were more progressive.

And so we would have these conversations. We would have a leader of the group introduce the topic, and then people were talking about what we value about the Methodist Church, what we’d leave behind if we could.

And then that turned into discussing various possible ways forward, which included the things we talked about: resist, dissolve the denomination and form something new or disaffiliate and form a new coalition or something that that looked like a modified CCP-type plan where we would find some structural way to hold as many people in the Methodist Church together as possible.

RELATED: United Methodist court upholds Traditional Plan’s ban on LGBTQ clergy, same sex marriage

But we don’t have clarity.

I would say many of the progressives who were there tended to favor leaving and forming something new. And I would say a slight majority of the centrists tended to favor staying and living into what we believe and continuing to work for change.

There was a sort of a two-pronged approach in the end: We’re going to continue to live into what we believe the church should look like, and, at the same time, we are going to be in conversations preparing for whatever the ultimate solution is.

Resistance is not a permanent solution. Resistance is a means to getting to another place.

At the town hall you held at your church immediately after the special session, you talked about the possibility of leaving the United Methodist Church and said you weren’t interested in becoming a nondenominational church. Why is being a United Methodist important to you?

It would be easier for our church to become nondenominational. But when I was 18, I actually felt called by God to be a Methodist, to be a part of a denomination, to help bring renewal and revival to that denomination.

I began studying John Wesley and the early Methodist movement and this idea of revival in the church — an evangelical revival that started on the campus of Oxford University by a professor at Oxford. There was this whole intellectual side of the faith, coupled with a fervent, passionate heart faith.

People say this to me: “I can’t figure you out. Are you liberal or conservative?” My answer is always, yes, of course. Do I have to pick? Because those two are really both important ideas — to be open to reform, generous in spirit, and at the same time to be conserving things that are the historic core of our faith.

Methodism is a both/and, not an either/or kind of faith. You move from that to this idea of this connection — that in the U.S. there are 32,000 churches and we are connected together. There’s an accountability that comes with that. And so all of that is part of the reason why we feel committed to these people in this community and don’t want to walk away from it.

Another idea you had mentioned during the town hall was possibly withholding parts of apportionments to the denomination. Is your church withholding apportionments, or do you know of any others that are?

There are a number of churches that have.

Typically, we pay in full at the beginning of the year every year as a way of expressing our commitment to the denomination and to those other churches. What we did this year is we had already paid the first half before General Conference, and we have withheld the second half. We will pay it before the year’s out.

We do want to express that what’s happened is not OK with us and that we want to have the church be prepared for what happens if churches like ours leave.