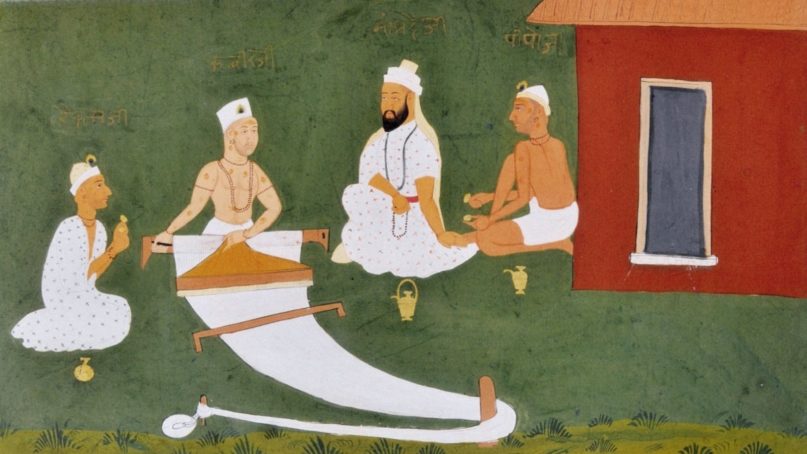

Kabir, second from left, weaves while talking with Namdeva, Raidas and Pipaji. Painting from Jaipur, India, early 19th century. Image courtesy of National Museum New Delhi/Creative Commons

This commentary was produced in partnership with the Pulitzer Center.

VARANASI, India (RNS) — Away from the congested roads of this northern Indian city, a narrow lane that more resembles a hallway painted with colorful motifs opens onto a central hall of the Kabir Chaura Math, a holy place dedicated to a low-caste Muslim weaver and poet of the 15th century.

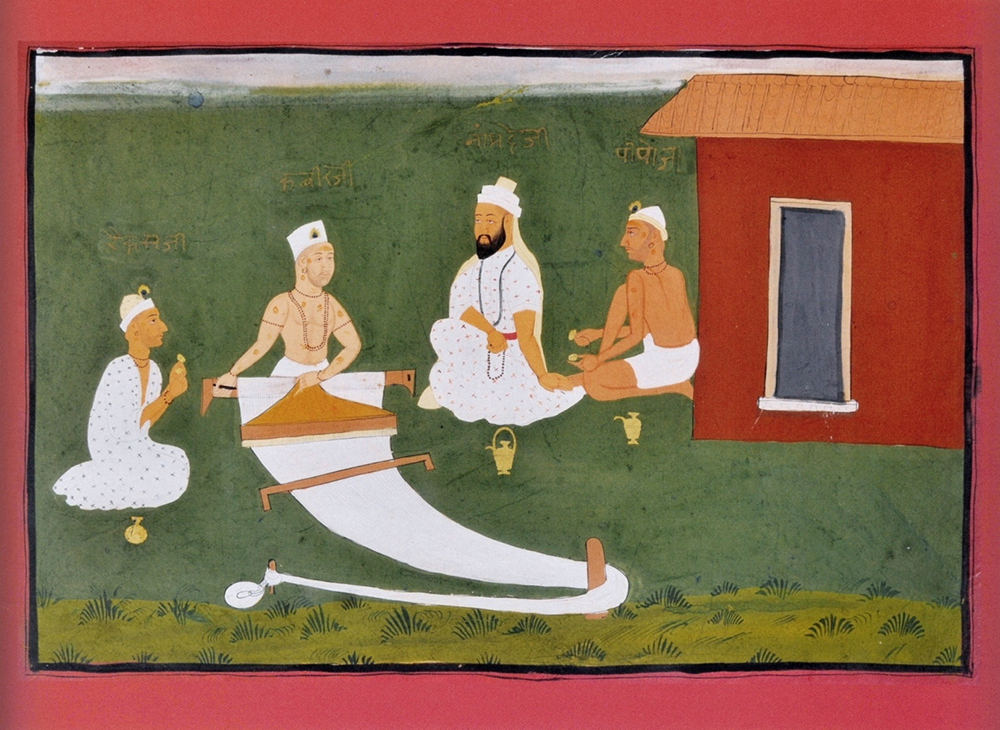

At a time when rising Hindu nationalism is dividing India, the Kabir Chaura Math is an architectural anomaly, featuring both mosque and Hindu temple domes — and a spiritual one: The ashram here draws hundreds of visitors a day, many of them young Indians who come to honor Kabir as a symbol of interfaith cooperation. (A large collection of Kabir’s couplets can also be found in the Sikh holy book, the Guru Granth Sahib.)

In India as in the United States, millennials are charting their own spiritual paths, and here they are reviving the spiritual teachings of a mystic who wrote couplets on the nature of the divine and criticized any form of orthodoxy.

The mosque-shaped dome, left, at Kabir Chaura Math in Varanasi, India. RNS photo by Shubhan Nagendra

The millennials’ attraction to Kabir is not out of keeping with what we know about their beliefs: Kabir stood for social justice and wrote verses castigating the ill treatment of the poor and vulnerable. But his life story also attests to the deep history of keeping harmony between the Hindus and Muslims of India.

As the story goes, Kabir was found abandoned as an infant near a pond by a Muslim couple, Neeru and Nima. Kabir grew up in their home learning weaving from his father.

Kabir’s attempts to educate himself were rebuffed by both upper-caste Hindus and Muslims, helping him to establish the theme in his poetry of opposition to the caste system. He urged Hindus and Muslims not to allow hateful rhetoric or religious leaders to affect them.

His defiance about existing religious beliefs tested ideas about the superiority, not to mention the validity, of the two faiths. It is said that as his death approached, Kabir left Varanasi, where many Hindus choose to spend their last days in the belief that this holy city leads to liberation from the cycle of birth and death, walking several miles to a nearby town where, it was believed, dying there resulted in entry to hell.

After he died, the legend goes, Hindus and Muslims were quarreling over his remains when Kabir’s body was changed into a bed of flowers. A voice then instructed people from the two religious communities to divide the flowers between them.

Both temple, right, and mosque, left, architecture can be seen at Kabir Chaura Math in Varanasi, India. RNS photo by Shubhan Nagendra

When I visited the ashram at Kabir Chaura Math (Hindi for “Kabir crossroads”) this summer, I encountered more than a dozen young people among the 50 or so who live at the Kabir Chaura, looking after the upkeep of the place and devoting themselves to deeper study of Kabir.

The mood is one of quiet contemplation. Kabir spent much of his life spinning yarn, composing his couplets and sharing them, and a central part of the Kabir Chaura Math is the Bijak mandir, or temple of Kabir’s thoughts. There visitors can see Kabir’s wooden footwear, his weaving warp and beam, a hand-powered flour mill and a water bowl from which he drank water.

The Bijak mandir sits on a large platform that allows visitors to rest and meditate on Kabir’s life in a green urban oasis. Around the platform of this temple are statues of other spiritual thinkers of Kabir’s time.

The graves of both his parents, Neeru and Nima, are also in the complex.

Umesh Pratap Singh has been coming to Kabir Math since 2006, when he was 16. Today he fronts a musical group called Tana Bana —”tapestry of rhythm” — that he hopes will take Kabir’s message to a larger audience.

Umesh Pratap Singh. RNS photo by Shubhan Nagendra

The mystic’s simple language, Umesh explained, conveys universal values by using kind words. In one of his couplets Kabir urges people to use only those words that are pleasant to hear. Kabir believed such language is beneficial not just for those hearing it, but also for those speaking it. To Umesh, Kabir’s is the language of love and religion.

“We sing Kabir’s poetry, so young people can understand him. People are lost in the political agenda, so we go to different places and do performances,” said Umesh. At their performances, his group talks to the youth about misinformation being spread by Hindu nationalists.

Among the claims of Hindu nationalists against Muslims is that their men are waging “love jihad,” a warlike effort targeting Hindu women to convert them to Islam through marriage. Umesh quotes Kabir from the stage, saying in Hindi, “Guru karo jaan ke, paani piyo chhan ke” — “Just as water needs to be filtered, before drinking, one should weigh the information one is consuming very carefully.”

Umesh sees Kabir as the antidote to the cultural split that religious nationalists are trying to provoke, one that meets their claims of India’s past as an exclusively Hindu culture. In answer to stories of a “love jihad,” he cites the fact that in Hindu-Muslim marriages, couples often call their children Kabir, to demonstrate the spirit of oneness of their faiths.

(Kalpana Jain is a U.S.-based religion journalist who worked for many years at India’s leading national daily, The Times of India. She was a Nieman Fellow at Harvard in 2009. The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily represent those of Religion News Service.)