(RNS) — I first heard Ram Dass speak while listening to a local radio show in my attic apartment in Haight-Ashbury in the late ’60s.

I was a psychedelic veteran and a temporary journalism dropout living the hippie dream, doing a bit of this and that to earn money and dividing my time between the Bay Area and a shack in coastal Mendocino County that had only intermittent running water.

He made sense, I thought. Soured on the dominant culture, his vision became mine, if not quite so finely articulated.

Over the decades that followed, I met with him many times as a journalist. I was, inevitably, both a chronicler and a student — one of millions of Boomers drawn to him.

RELATED: Ram Dass, who introduced a generation to Hindu meditation, dies at 88

The gift of knowing Ram Dass on each of these levels was that I came to view him as a person as flawed as the rest of us. Nonetheless, I never lost my admiration for his great willingness to share his imperfections with the world and his ability to laugh about them.

His core lesson, as I came to understand it, was that you’re fine just the way you are as long as you continue to cultivate your vulnerability, for that’s where true love lies, and your compassion toward others, including other life forms.

On Sunday (Dec. 22), Ram Dass, born Richard Alpert, the iconic consciousness adventurer, died in Hawaii at 88. He will always be remembered for his early advocacy, alongside Timothy Leary, of psychedelic drugs as a spiritual boon, a snapshot of the experimentalism of the 1960s no less than my apartment in the Haight.

But his legacy can best be seen in the burgeoning “spiritual but not religious” movement that continues to siphon dissatisfied, mostly young, people from the traditional Western religious faiths.

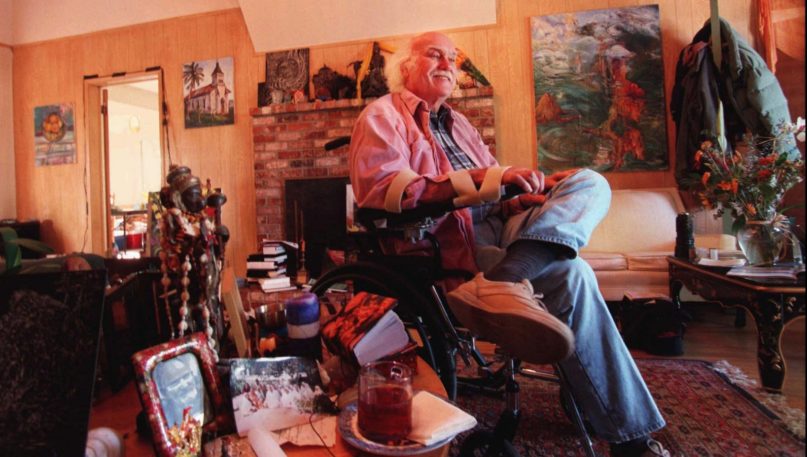

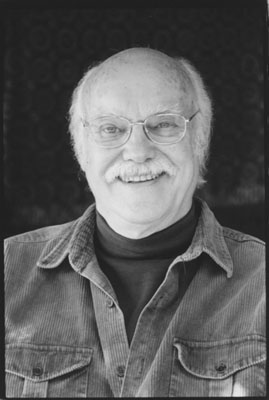

Ram Dass. RNS file photo

Ram Dass first drew notice as a spiritual leader in 1971, with the publication of his first book, “Be Here Now.” It quickly became a must-read for those seeking life lessons after the hippy scene descended into chaos and excess. To date, it has reportedly sold more than 2 million copies.

Physically limited by a severe stroke in 1997, early this year he told The New York Times that he was ready to die, which he did at his home on Maui, just days after hosting his annual retreat that featured meditation teachers from around the world.

His accessibility is what made Ram Dass so likable to so many — a simple humanity that turned on others. Here’s one example of what I mean.

In the late 1980s, Ram Dass was the featured speaker at a conference in Santa Rosa, California, organized by the International Transpersonal Association, with which I was associated as a media consultant. The hall in which he spoke was packed with several thousand who revered him, to varying degrees, as their guru, their spiritual teacher.

In the self-deprecating style he employed so effectively, Ram Dass recounted his life’s attempts to overcome what Buddhists call “monkey mind,” the incessant mental chatter that can drive us to emotional despair.

He noted the many years he’d spent in psychotherapy. He noted his years of psychedelic drug use. He noted the dissatisfaction he still felt until he encountered his Indian guru Neem Karoli Baba in 1967 and his years of meditation.

The audience collectively leaned forward, waiting for Ram Dass to sum up all he had learned that presumably allowed him to tame his monkey mind and attain the happiness so many of his listeners undoubtedly craved for themselves. I listened from the back of the hall as he reached the telling moment that would make the conference’s steep admission price worth it. You could hear a pin drop.

“And after all that,” I remember him saying. “After all that effort, I can tell you” — here he paused for maximum impact — “I have not overcome one single neurosis.”

A collective sigh of disappointment was heard. ‘Then what is the point of wrestling with our demons,’ seemed the unstated question.

“But what has changed is how I relate to them.”

Again, embrace who you are and work with it, was his point. See the divine spark within you and in others and fall in love with it. Stripped of its cosmology and philosophical trappings, that was Ram Dass’ simple message.

The son of a president of the New Haven Railroad, Richard Alpert was brought up in a well-off home in Boston, practicing what he labeled a form of “hollow” Judaism. He had long abandoned that perfunctory religiosity by the time he joined Harvard University’s psychology and social relations departments as a teacher, and the graduate school of education and the school’s health department, where he served as a therapist.

Forced out of Harvard in 1963 along with Leary for his open experiments with psychedelics (and for giving drugs to an undergraduate student), he transformed into a Western version of the wandering Hindu, sadhu or holy man. Not until early in 1992 did he publicly confront his Jewishness in a talk he gave at the University of Judaism in Los Angeles.

Until then, Ram Dass had eschewed any overt Jewish connection — other than the sarcastic sense of humor that evoked an enlightened Borscht Belt comic. He had only consented to the Los Angeles talk because, he said, the widow of a long-time supporter had invited him to honor her late husband, who had been associated with the University of Judaism, the West Coast center of Conservative Judaism.

I was the first journalist he spoke to in advance of his talk. Why he graced me with an interview I no longer remember, except that at the time I wrote for a prominent American Jewish newspaper, and the people at the University of Judaism knew of me.

He told me he had previously avoided appearing in a Jewish setting because of the criticism he had received from traditional Jews who blamed him and his ilk for leading many young Jews away from the faith and into drug use and, to his critics, superficial, untethered spirituality.

Like Bob Dylan, who strayed into evangelical Christianity before returning, in his own fashion, to Judaism, Ram Dass was a potential feather in the cap for any Jewish leader who could lure him back to his roots. This, too, was why he kept his distance from the Jewish world. He didn’t want to be played, he told me.

To prepare for his talk, he purchased a slew of books on Judaism and retreated for several months to an island in the South Pacific to bone up and write his talk. He did not, he told me, want to embarrass himself or his by then deceased father, who had been a founder of the Jewish-affiliated Brandeis University.

Neither did he betray who he was, a spiritual adventurer who forged forward, not back. He delivered his talk on Judaism’s inherent spirituality, showing himself to be the serious scholar of human consciousness he had been at Harvard.

Afterward, he returned to his preferred blend of Hindu and Buddhist spiritual practice.

(Ira Rifkin is a former Religion News Service national correspondent. He lives in Annapolis, Maryland. The views expressed in this commentary are his own.)