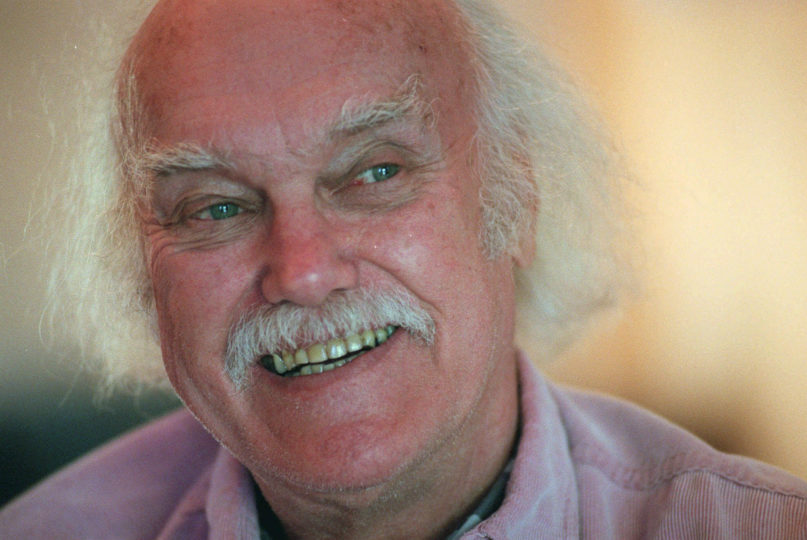

(RNS) — Ram Dass, a spiritual pied piper who introduced a generation of young Americans to Hindu meditation, died Sunday (Dec. 23) in Maui, Hawaii, where he lived and taught. He was 88.

Dass’ psychedelic drug experiments together with LSD advocate Timothy Leary led him out of the halls of Harvard University and into the hills of an Indian ashram.

Dass was always religiously restless. He was raised in Judaism, which he initially found uninspiring, before pioneering the use of psychedelic drugs as a spiritual practice. He eventually sought meaning in Buddhism and Hinduism, which took him to India and resulted in his 1971 best-selling book “Be Here Now.”

RELATED: A spiritual icon to the Boomers, Ram Dass was godfather to the ‘nones’

In subsequent years, he focused on several spiritual projects, including “conscious aging and dying,” a sort of rebranding of the end of life as a time not of decay and ending but of wisdom and fulfillment.

In 2018, Dass’ own conscious aging and dying became the subject of a short documentary called “Ram Dass, Going Home” by filmmaker Derek Peck.

“Richard Alpert’s transformation into Ram Dass — from the Harvard professor to LSD evangelist to East-meets-West spiritual teacher — was in many ways the personification of the tumultuous cultural changes of the 1960s,” said Don Lattin, author of “The Harvard Psychedelic Club,” which chronicled Dass’ and Leary’s LSD-feuled spiritual experiments.

“He helped many of us make sense of the long, strange trip and find a way to channel whatever drug-induced insight we may have had into positive changes in the way we live our actual lives,” said Lattin. “There are lots of reasons why everyone seems to be talking about ‘mindfulness’ today, or taking yoga classes, but one of those reasons is the life of Ram Dass.”

Ram Dass was born Richard Alpert in Boston on April 6, 1931 to parents who were Jewish, a faith he later said he found “hollow.” By the time he entered Tufts University, he considered himself an atheist.

Alpert studied psychology and landed a teaching position at Harvard University in 1958. There, he met fellow psychologist Timothy Leary, and the two began working on their Harvard Psilocybin Project, an investigation into the therapeutic uses of psychedelic drugs like LSD.

Alpert and Leary believed the use of psychedelics could lead to spiritual and religious enlightenment. They were joined in some of their experiments by a who’s who of mid-20th century luminaries — religion scholar Huston Smith, writer Aldous Huxley and poet Allen Ginsberg among them. In 1962, the pair founded the International Federation for Internal Freedom to expand those experiments, and within a year the pair were dismissed from Harvard.

In 1963, the IFIF moved to the estate of a sympathetic heiress and for the heart of the decade Leary and Alpert looked for a path to enlightenment through psychedelics. They taught and wrote, eventually co-authoring, with Ralph Metzner, “The Psychedelic Experience,” which was based on the “Tibetan Book of the Dead.”

Still restless in 1967, Alpert took a trip to India where he met the Hindu yoga teacher Neem Karoli Baba. Baba, whom Alpert called “Maharajji,” gave him the name Ram Dass, which means “servant of God.” Dass returned to the U.S. in 1968 and spent parts of the next three years writing what would become the 415-page “Be Here Now.”

Part spiritual cookbook, part diary, and part free-verse poetry, “Be Here Now” introduced Dass’ generation to Eastern mindfulness practices in a plain, straight-forward writing style that resonated with them.

“It’s only when caterpillarness is done that one becomes a butterfly,” Dass writes in “Be Here Now.” “That again is part of this paradox. You cannot rip away caterpillarness. The whole trip occurs in an unfolding process of which we have no control.”

The New York Times said the book, “achieved wide-ranging currency during the cultural revolution of the time.” Tech giant Steve Jobs, Beatle George Harrison, self-help author Wayne Dyer and poet Lawrence Ferlinghetti all credited “Be Here Now” with expanding their spiritual horizons.

“A self-described ‘manual for conscious being,’ it is charged with antic energy,” filmmaker Michael Almereyda said of the book in 2002. “It opens out, in its exuberant middle stretch, into a kind of cosmic comic strip, pages printed on brown paper with prototypically ‘psychedelic’ line drawings blossoming around blocks of text set ALL IN CAPS and running up the pages at right angles, requiring the reader to turn the book on its side.”

He authored or co-authored 15 books, but none achieved the spread or impact of “Be Here Now,” which has remained in print since its publication and has reached more than two million copies in print.

In the 1970s, Dass turned to other spiritually driven projects, including the Prison Ashram Project, which brought Eastern religion and philosophy to the incarcerated, and the Seva Foundation, an international health organization.

As Dass aged, he became more focused on conscious aging and dying, teaching workshops, retreats and working with different foundations to banish the fear of death. In 1992, after an invitation to address Jewish spirituality, he came back into conversation with the Judaism of his youth.

“I have always said that often the religion you were born with becomes more important to you as you see the universality of truth,” Dass told Religion News Service in 1992. “The one you start with is often the one you come back to, once you learn to go beyond the negative experiences you have as a child.”

In 1997, Dass suffered a near-fatal stroke that left him paralyzed on one side and suffering from “expressive aphasia” — the inability to produce language easily.

Dass turned the stroke and his partial recovery into his 2000 book, “Still Here: Embracing Aging, Changing and Dying.”

“It’s all grace,” he told the Huffington Post in 2013. “The stroke graced my spiritual work because it took me inside.”

After the publication of “Still Here,” Dass relocated from Marin County, California, to Hawaii. After a severe infection following a 2004 trip to India, he announced he would no longer travel.

Instead, he arranged to teach visitors to a guest house located on his rented property, just off the road to Hana on Maui’s north shore. There, guests would meditate, cook and eat together with Dass and swim with him in the ocean.

In 2013, writer Andréa R. Vaucher traveled to Maui for one of Dass’ retreats and wrote about it for Tricycle magazine. She described Dass, then 82, as “a beacon for the aging baby boomer population, one step ahead on the journey toward physical decline and eventual death.”

In his ninth decade, Vaucher reported that Dass said of death, “The medical establishment does everything it can to keep someone alive. This culture says, ‘Don’t go, don’t go,’ and priests or rabbis say, ‘It’s okay to go.’ You need to stay in the middle. Don’t let your model of death interfere.”