President Donald Trump speaks at the Students for Trump conference at Dream City Church on June 23, 2020, in Phoenix. (AP Photo/Ross D. Franklin)

(RNS) — Shock. Betrayal. That’s the response that millions of Americans had after the 2016 presidential election when they learned that 80% of white evangelicals voted for Donald Trump. How could believing Christians vote for him in the first place, and then continue to approve of a presidency that has been marked by scandal, authoritarianism and racism?

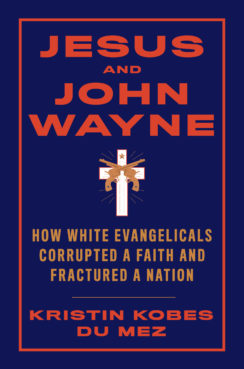

Kristin Du Mez was shocked too, but perhaps not as stunned as the rest of America. A historian who teaches at Calvin University in Michigan, Du Mez says in her new book, “Jesus and John Wayne: How White Evangelicals Corrupted a Faith and Fractured a Nation,” that evangelicals’ seduction by Trump has been coming for a long time.

They weren’t hoodwinked or misled by Trump, Du Mez believes. Nor were they holding their noses and voting for him in order to get anti-abortion Supreme Court justices. Instead, they like him. And they’ve been preparing for him for decades.

“Evangelical support for Trump was no aberration, nor was it merely a pragmatic choice,” Du Mez writes. “It was, rather, the culmination of evangelicals’ embrace of militant masculinity, an ideology that enshrines patriarchal authority and condones the callous display of power, at home and abroad.”

Historian Kristin Du Mez. Photo credit: Deborah K Hoag

Du Mez started connecting the dots of militant patriarchy and what she calls “family values evangelicalism” more than 15 years ago, when her students were passing around John Eldredge’s “Wild at Heart,” which encouraged a generation of Christian men to embrace their rugged, natural inner warrior.

Eldredge’s book, which sold millions of copies, joined other examples of a particular kind of masculinity that had long been promulgated by Christian right authors such as James Dobson, Jack Hyles and Eric Metaxas, all of whom connected Christian masculinity to violence or the threat of violence. Dobson made his mark in the 1970s encouraging parents to spank their children. A decade ago, Metaxas recast theologian Dietrich Bonhoeffer as a daring WWII spy.

“When I looked back historically, I could see how the militant masculine ideal was built up and embraced for decades,” Du Mez said in an interview. “If you go back to the 1960s and 1970s, this is a time when evangelicals were beginning to mobilize as a partisan political force, coming together as the religious right we know today. They were reacting against both the rise of feminism — they’re really emphasizing gender difference — and the Vietnam War.”

For evangelicals, she noted, Vietnam pitted Christian America against the threat of communism. When America lost, they “were deeply disturbed by this, and judged it as a failure of American manhood.”

In addition to feminism and communism, white evangelicals of the era spied another threat: desegregation. Particularly in the South, evangelicals’ political mobilization occurred around issues of race.

“When you look at how they are justifying segregation,” said Du Mez, “it’s about seeing white men as protectors of vulnerable white womanhood, and the rights of the family over and against the federal government. This militant evangelical masculinity that I write about is a distinctively white masculine ideal.”

It was to face these threats, foreign and domestic, that God made men strong, said Du Mez. “He gave them testosterone to make them aggressive so that they can defend their family, their church and their nation.”

These same three menaces — feminism, war and racial equality — came into play in the 2016 election. White evangelicals found the specter of Hillary Clinton as president terrifying enough that they gladly took cues from GOP candidate Trump in chanting “lock her up” and labeling her a “feminazi.”

They craved a strong military in a post-9/11 era, especially since now, unlike with the Vietnam conflict, the threat was on American soil. Trump played into their Islamophobia by promising to ban Muslim travel and “bomb the shit out of” ISIS. He played into their racial fears by blaming immigrants for many of America’s problems and claiming he would build a wall to forever end illegal immigrants from Mexico.

In short, Trump was telling white evangelicals what they had long wanted to hear.

Du Mez, who grew up in conservative white Christian circles and remains a practicing Christian, was initially hesitant to delve into her topic. She wondered if the “militant white patriarchy” strand of American evangelicalism might not just be a minority voice within the tradition.

Du Mez, who grew up in conservative white Christian circles and remains a practicing Christian, was initially hesitant to delve into her topic. She wondered if the “militant white patriarchy” strand of American evangelicalism might not just be a minority voice within the tradition.

Then the 2016 election showed her that the “Duck Dynasty”-watching, John Wayne-adoring crowd was not the fringe but the mainstream. Trump’s blunt militancy was a feature, not a bug.

While observers wonder how evangelicals overlooked Trump’s three marriages, multiple affairs and boasts of sexual assault, Du Mez said that evangelicals had years of practice. Pastor after pastor has been embroiled in scandal, often involving sexual misconduct or other abuses of power.

“There’s such a culture of deference in evangelical churches and communities,” said Du Mez. Bill Hybels, the founder of Willow Creek, the influential megachurch in the Chicago suburbs, was forced to resign over his conduct with women over the course of years.

Mark Driscoll, the lead pastor of Mars Hill Church in Seattle, resigned in 2014 because of years of a “domineering style of leadership” and accusations of abusive behavior.

There is a common thread here, said Du Mez, though it’s more overt with people like Driscoll. “Mark Driscoll is the extreme example of this militant patriarchy. You can see it prominently in his writings on sex and gender, in his church leadership, his authoritarian style, his militarism, and how he really worked to generate a sense of threat within his own church.”

Church members, she says, “were taught to fear the outside, and even to fear the church down the street, because there were enemies everywhere that were going to undermine truth.”

Driscoll, who founded a new church in Arizona, continues as a popular leader, reflecting white evangelicalism’s habit of propping up authoritarian men. “Even after his downfall, you have a lot of his friends and admirers who are lamenting what happened to him because he was a ‘great Christian brother’ and ‘such a gospel witness,’ and not deconstructing his corruption of Christianity and seeing that that is where the problem was,” said Du Mez.

Du Mez notes that evangelicals often punish people, like Jen Hatmaker or Rachel Held Evans, who call out their toxic culture, supporting a climate of secrecy. For her part, Du Mez said she has not received much hate mail in the month since “Jesus and John Wayne” was published, despite the book’s clear denunciation of abuses of power.

“I have been overwhelmed by amazing letters of support,” she said. “I get several every day from evangelicals themselves — some who walked away, some who stayed in. These are heartfelt personal testimonies, almost all of which say something like, ‘This is the story of my life, but I never understood how all of these pieces fit together.’ There’s almost this catharsis of being able to name what happened and to understand that their own experiences were part of this much bigger story, and they weren’t alone in bumping up against the harsh edges of this ideology.”

Related content:

Why white evangelicals voted for Trump: Fear, power and nostalgia

Donald Trump is not a Christian, but he knows what the religious right needs to hear, says historian