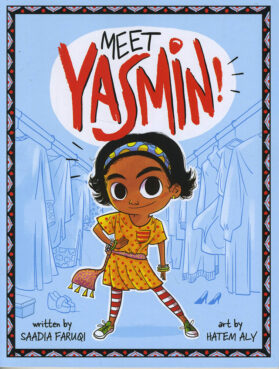

(RNS) — When Intisar Khanani’s children read “Meet Yasmin!,” the first book in Saadia Faruqi’s children’s book series, they burst into amazed laughter.

“They were like, ‘Look, Mommy, it’s our family! The mommy is a writer, and the daddy is a teacher,’” she recalled. “I was like, ‘Yeah … how did she write us?’”

Faruqi’s award-winning series for early readers follows second-grader Yasmin and her Pakistani American Muslim family as they go about their daily life, playing soccer and visiting a farmers market. “The Yasmin series has really revolutionized stories for Muslim kids,” said Khanani, the author of three young adult novels herself. “It’s been wonderfully successful and opened up pathways for other writers.”

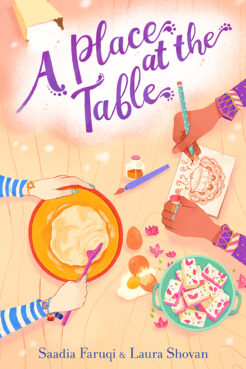

Now, Faruqi has several more middle-grade books ready to go. The recently published “A Place at the Table” explores the lives of first-generation immigrants through the story of two young girls — one Pakistani American, the other Jewish British American — who meet in a South Asian cooking class. In “A Thousand Questions,” coming in October, a Pakistani American girl’s trip to her family’s homeland leads to an unexpected friendship with a young servant who works in her grandparents’ home.

Faruqi spoke to Religion News Service about how her writing draws on her two decades as a Muslim interfaith activist in Texas post-9/11 as well as the lives of her own two children. This interview has been edited for clarity and length.

Your writing is full of interfaith encounters. How did that become a theme for you?

I came to the U.S. just before 9/11. I told the ladies at my mosque, “How about we invite somebody or do something?” We made friends with the local church, I started a women’s interfaith book club that’s been going for almost 11 years now. Then the Houston Police Department invited me to do a yearlong training for all of their officers about Islam. My interfaith activism grew from that.

Several years down the road I was still getting so many questions and all this resistance and animosity. I got frustrated and burnt out. But I also realized that whenever I told stories, it would make more of a connection and an impact. Stories have a power that facts don’t, which is kind of sad but true.

So in 2015, I published an adult short story collection, “Brick Walls.” A lot of people including my own family said, “You were doing this, now you’re doing something totally different, how flaky are you?” But the mission is the same as my interfaith activism, even when I’m doing children’s books. The purpose is to present a positive view of Muslims — or rather, a realistic one. It might be flawed, it might not be a very good representation of Islam all the time, but it’s something I want people to learn from and understand.

Why the shift to books for kids?

I find that children’s books are so much easier because kids are so open to reading different perspectives. They want to learn, they’re excited. They don’t have these preconceived ideas that they already hate this culture or that these people are bad.

Everything I’ve written so far has been a reaction to what I have seen my own children grappling with. I wrote Yasmin, which is my early reader series, when my daughter was in kindergarten. She kept saying, “These people don’t look like me.” So I wrote a story about a girl who looks and acts like my daughter.

I’m never really thinking about whether it’s middle grade versus a picture book. I’m just thinking about filling the internal need for my family. And right now they’re in middle school.

“A Place at the Table” was co-written with Laura Shovan, with the chapters alternating between your perspectives as Pakistani American Muslim and a British American Jew. What do you think readers will learn from that?

“A Place at the Table” by Saadia Faruqi and Laura Shovan. Courtesy image

Laura had been long thinking of writing a story about immigration. She has a British mom, so all her life she had been grappling with being a first-generation kid from one side. But she’s white, and she realized she didn’t have the struggles that many other first-generation kids face. In America, someone who has a British accent is cool. If you have a Pakistani accent, you’re not. So she asked me to be a part of it.

Essentially, it’s a friendship story about a Muslim girl and a Jewish girl. My interfaith work has always been about how to set aside our differences and focus on what we can all identify with.

We also wanted kids to take away how to be good allies. There’s a scene where Elizabeth’s friend says something really Islamophobic to Sara, and Elizabeth doesn’t say anything. She’s just quiet. When they leave, Sara has to sit down and explain why that was wrong, that friendship means that you stand up for someone. Learning how to not stay quiet if you see injustice happening is an important skill for kids. They see so much of this in the playgrounds, in the schools, even online or when playing video games. We do that too, right? We’re just quiet because we don’t know how to react. But that’s how it spreads.

How do you approach writing Muslim characters for kids?

I try to raise my kids in a really positive Islamic environment, but I know they still do things that I wouldn’t approve of. If I want to talk to kids who are real, not robots, then I have to talk at that level.

You know, there’s something we call Islamic fiction. Mostly their audience is kids who are Muslim. But I’m kind of uncomfortable with it. I don’t think they show reality.

In Islamic fiction, if there’s a woman, she is always wearing hijab. When there’s a mother or a daughter alone in their room at night, they’re still wearing their hijab. I’m not going to wear a hijab in my daughter’s bedroom at night. That’s not how we dress.

In the Yasmin series, we have her mom not wearing hijab when she’s inside, and then she puts it on when she goes outside. That’s a subtle way to teach something. The question is probably in a lot of people’s minds but they feel foolish asking it, so we have this whole misconception that never gets answered, because nobody’s willing to be the dumb person who asks the question. I reach into my memories of those conversations that I’ve had as an interfaith activist over the last almost 20 years now and put those little nuggets in what I write.

Are mainstream publishers becoming more open to these kinds of narratives?

There was a time when a publisher would say, “Well, we published one story about Pakistan, we’re not doing that again.” Now, for example, at HarperCollins, my editor has several Muslim authors she publishes. Sometimes that’s all she’s doing. That only changed in the last four or five years. We see a lot more Muslim writers getting recognition. There is room for those stories.

“Meet Yasmin!” by Saadia Faruqi. Courtesy image

But there are people who’ve been doing it when it was not easy. There’s Na’ima B. Robert. Her book “She Wore Red Trainers” came out in 2014, and she has a bunch of other books from even earlier. There’s Hena Khan, who everybody knows now, and Randa Abdel-Fattah, who wrote “Does My Head Look Big in This?” in 2005. They’ve proven that there is a market. Your story just has to be good enough.

What advice do you have for parents, librarians and teachers looking for books for their kids?

Make sure a lot of different cultures, religions and viewpoints are explored, but then also make sure that there’s diversity within that. If you get one Muslim author, and say, “Well, that’s my Muslim quota, now I’ll move on to the next diversity checkbox on my list,” that’s really wrong.

We have a problem now where there are suddenly a lot of Muslim writers and stories, but it’s become very skewed towards a certain kind of Muslim story. South Asian Muslim writers are probably the most right in the industry right now, especially for kids books.

There are a few Black Muslim writers that I’m really excited about. There’s Jamilah Thompkins-Bigelow, who has a couple of picture books out. The latest is “Your Name Is a Song.” There’s also Ashley Franklin, who wrote “Not Quite Snow White.”

Even within the Muslim book world, there’s so many different viewpoints and experiences. Showing more parts of it is important because the reader really gets a more rounded-out view.