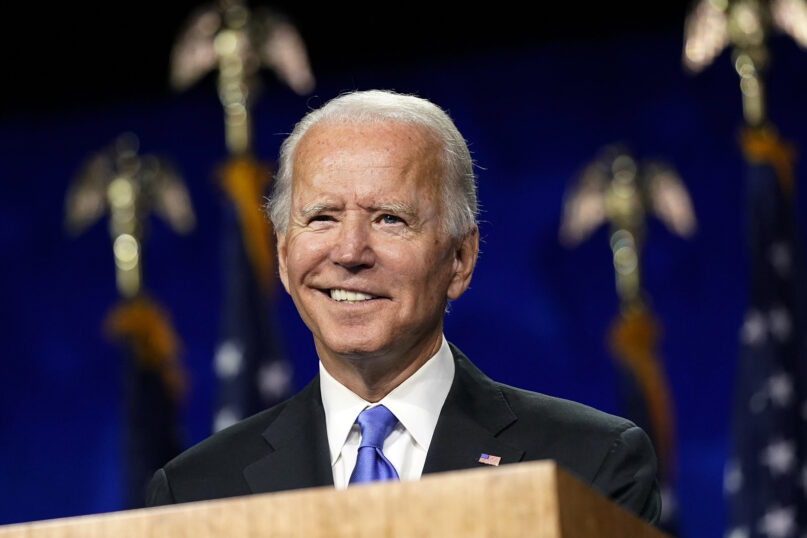

(RNS) — Joe Biden, a Roman Catholic, is running for the United States presidency. It hasn’t happened very often; there have only been three others nominated in our national history.

The first was New York Gov. Alfred E. Smith in 1928, followed by Massachusetts Sens. John F. Kennedy in 1960 and John F. Kerry in 2004.

Biden has openly described how his deep religious faith sustained him through the dark moments of his life, especially the tragic deaths of his first wife and two children. Biden is, in many ways, doubling down on his faith during his campaign, in the hopes of attracting Catholic faithful and religious voters who may see President Donald Trump’s use of faith as hypocritical.

In fact, Biden is counting on his Catholicism to be a boon to his campaign — but that hasn’t always been the case for Catholic presidential hopefuls.

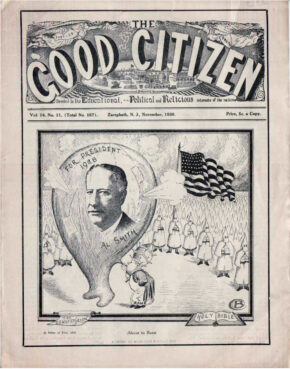

It certainly was not for Smith, who ran against U.S. Commerce Secretary and Republican Herbert C. Hoover. Back then, the religious bigots publicly charged that the New York governor’s religious loyalty to Pope Pius XI superseded his faithfulness to the Constitution and made him unfit, even dangerous, to sit in the Oval Office.

The obscene anti-Catholic attacks on Smith came not only from members of the anti-Catholic, anti-Semitic and anti-African American Ku Klux Klan and other hate groups. There were also strong anti-Catholic feelings deeply embedded among the clergy and laity of many Protestant denominations, including the Southern Baptist Convention and the Methodist Church.

Political cartoon suggesting the pope was the force behind Al Smith. The Good Citizen, November 1926. Publisher: Pillar of Fire Church, New Jersey. Image courtesy of Creative Commons

In addition, the New York City-born Smith spoke with a “Brooklyn accent,” was a fervent “wet” (a foe of Prohibition) and was particularly alien to many voters in white rural America.

Some bigots spread the rumor that Pope Pius XI had literally packed his bags and was planning to move into the White House if Smith became president. Such attacks reflected the widespread belief that Catholic politicians were not free from total Vatican control on all public policies.

Smith replied in anger: “I recognize no power in the institutions of my Church to interfere with the operations of the Constitution … or the enforcement of the law of the land. I believe in the absolute freedom of conscience … in the absolute separation of church and state. … I believe that no tribunal of any church has any power to make any decree of any force of law of the land, other than to establish the status of its own communicants within its own church.”

Many religious leaders spoke out against the anti-Catholicism of the day, none more forcefully than Rabbi Stephen S. Wise, the most prominent Jewish leader of that era. He repeatedly assailed the anti-Catholic hatred hurled at Smith: “Religious bigotry is engulfing the nation … my answer was … to remember that America meant a new start in the life of the world. If America meant to me nothing more than a perpetuation of the past, then the promise of America would come to naught.” The rabbi campaigned hard for his friend, Smith.

Three weeks before the election, Wise delivered a nationwide radio address supporting Smith. The rabbi attacked religious prejudice and urged voters to live up to the highest ideals of fairness and justice when they cast their ballots.

But the 1928 election was an easy win for Hoover. Smith carried only eight states and won but 40% of the nearly 37 million votes cast. Surprisingly, Smith narrowly lost his home state of New York although he had been elected governor four times in a row.

But even in defeat, Smith established the electoral foundation of a long-lasting Democratic urban coalition by winning 12 of the largest cities in the country. His strongest support came from recent immigrants, including Irish, Italians, Greeks, Jews, Poles and Russians, as well as the few African Americans who were able to cast a ballot in 1928.

Wise consoled his friend after the election: “… you made a brave fight … I shall always remember with joy and pride that I fought … under the banner of your leadership … A happier day for America may yet dawn.”

The rabbi was correct. Four years later, another New York governor, Franklin D. Roosevelt, building upon the ruins of Smith’s loss, soundly defeated Hoover and the Republicans. The GOP did not win another presidential election until 1952, and eight years later JFK, despite the anti-Catholic attacks led by the Rev. Norman Vincent Peale and others, was elected president.

In an ironic twist of history, it was Jimmy Carter, a devout Southern Baptist, who as president in October 1979 warmly welcomed Pope John Paul II to the White House. An observer wryly remarked that the Polish-born pope did not bring his luggage with him on the visit.

Of course, neither he nor any other pope has “moved into the White House.”

(Rabbi A. James Rudin is the American Jewish Committee’s senior interreligious adviser and the author of “Pillar of Fire: A Biography of Rabbi Stephen S. Wise,” which was nominated for a 2016 Pulitzer Prize. He can be reached at jamesrudin.com. The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily reflect those of Religion News Service.)