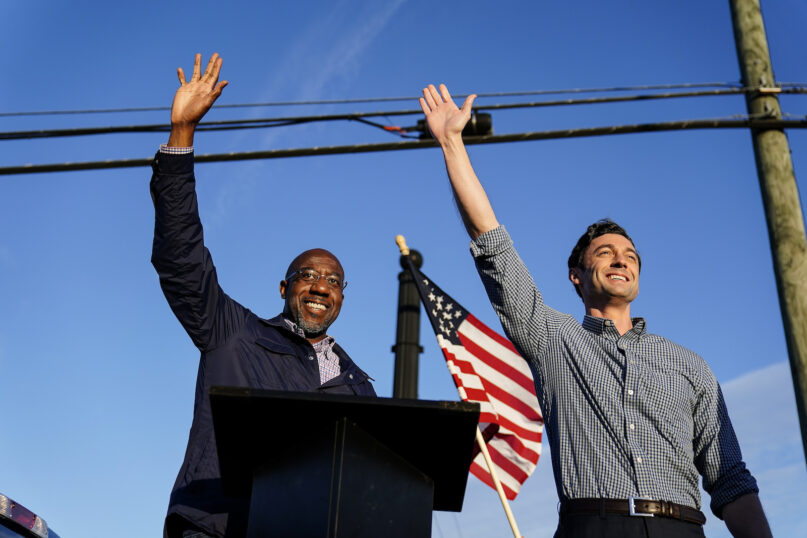

(RNS) — Not since Cleavon Little and Gene Wilder teamed up to save Rock Ridge from the bad guys in Mel Brooks’ “Blazing Saddles” half a century ago has there been a Black-Jewish buddy story like Raphael Warnock and Jon Ossoff’s joint runoff campaign in Georgia.

It’s about a Black Baptist preacher and the young Jewish go-getter the preacher calls “my brother from another mother” who, in a scenario that rivals any in American political history, have the eyes of the nation on them as they seek to oust two Republican incumbent senators and give control of Capitol Hill to the Democrats.

If “Blazing Saddles” sends up the classic Hollywood Western, the Warnock-Ossoff story is classic Atlanta.

When I moved to Georgia to work for the Atlanta Journal-Constitution in 1987, the Black-Jewish alliance of the civil rights era was a distant memory in the North, victim of the bitter 1968 New York City teachers’ strike and tensions over affirmative action programs. But in Atlanta the alliance was alive and well.

Local Jews were big supporters of the King Center, and whenever there were citywide good works to do, they got done in no small measure thanks to longstanding relationships between leaders of Atlanta’s Black and Jewish communities.

The experiences of the two communities had run parallel since the Civil War.

Starting out life as a railroad terminus before the war, Atlanta was the kind of open place where Jews and Blacks could thrive, and did. Henry Grady, editor of the Atlanta Constitution, made a career of preaching the gospel of the New South to northerners. It was commerce and industry, not antebellum nostalgia and racism, that made “the city too busy to hate” (as Atlanta later called itself) tick.

But by the end of the 19th century, Atlanta’s white Christian elite became intent on disenfranchising its Black residents and pushing the Jews out of its social clubs and corridors of power.

In 1906, stirred up by newspaper reports of sexual assaults on white women by Black men and a stage version of Thomas Dixon Jr.’s novel “The Clansman,” white mobs rioted through Black neighborhoods and business districts, massacring at least two dozen Black Atlantans.

In 1915, a white mob lynched 31-year-old Leo Frank, a prominent member of the Jewish community who two years earlier had been (falsely) convicted of murdering a 13-year-old girl who worked at the pencil factory he managed. In his 1973 history “The Provincials,” Eli Evans portrays Jews in the South as occupying a liminal space between whites and Blacks, and nothing demonstrated their liminality to Atlanta’s Jews more than the lynching of one of their own.

As Melissa Fay Greene recounts in “The Temple Bombing,” Jewish memory of what happened to Leo Frank was alive and anxious in the 1950s, when Pittsburgh-born Jacob Rothschild, rabbi of Atlanta’s biggest and oldest synagogue, began actively supporting the nascent civil rights movement. The anxiety was realized In 1958, when The Temple was bombed by white supremacists.

But as a result, the Atlanta Jewish community earned a special place in the civil rights struggle, one memorialized in “Driving Miss Daisy,” the play and well-known movie by Atlanta native Alfred Uhry. The friendship between an elderly Jewish lady and her Black chauffeur may sit awkwardly in the age of Black Lives Matter, but its central scene of Miss Daisy attending a dinner speech by Martin Luther King Jr. as Hoke the chauffeur listens on the radio outside indelibly captures the complex, intertwined relationship of Black and Jewish Atlanta.

The friendship between Warnock, who today occupies King’s position as senior pastor of historic Ebenezer Baptist Church, and Peter Berg, The Temple’s current chief rabbi, amounts to a keeping of the faith. For more than a decade, the two have spoken at each other’s house of worship during MLK weekend.

After the Tree of Life Synagogue massacre in Pittsburgh, Warnock was the first person to call Berg to commiserate. Small wonder that the Republican effort to portray him as an anti-Semite for criticizing Israeli policy toward the Palestinians has done little to dampen Jewish enthusiasm for his candidacy.

As for Ossoff, it was by reading about the civil rights movement that this 33-year-old son of a well-to-do Atlanta businessman was inspired to work for Black politicians. As an undergraduate at Georgetown University, he impressed the late Congressman John Lewis sufficiently to receive an unpaid internship in Lewis’ office, then talked his way into a job helping Rep. Hank Johnson win his seat in Congress and worked for him for five years.

Three years ago, Ossoff rose to political prominence when he ran in a special election and nearly flipped Georgia’s sixth congressional district, once represented by Newt Gingrich. It includes part of Marietta, where Leo Frank was lynched, and a major chunk of Cobb County, which back in the day refused to allow the subway from Atlanta to cross its border because it didn’t want Black people coming in.

Today, the sixth district is 40% minority. In 2018, Democrat Lucy McBath became its first Black representative by beating Republican incumbent Karen Handel in a close contest. In a rematch in November, McBath won handily.

That’s the new Georgia. If the Warnock-Ossoff campaign prevails on Tuesday, the state will never be the same.