LOS ANGELES (RNS) — Lydia Lopez was demonstrating in a picket line in 1968 to support Mexican American educator and activist Sal Castro, who was removed from the classroom after participating in the historic student walkouts, when UCLA professor Juan Gómez-Quiñones told her of a party at the Church of the Epiphany.

Lopez loved parties so she decided to go. The Episcopal parish, located in the Los Angeles neighborhood of Lincoln Heights, was embellished with papel picado. Lopez could hear mariachis playing. She recalled being overwhelmed with emotions as she saw how a place of worship embraced her Mexican American identity.

“I wept because I needed a place as a Chicana, and I needed a place as a Christian to call home,” said Lopez, who had gone years without being involved in a church after growing up in a Baptist church that she’d come to feel was too conservative.

The Church of the Epiphany, founded in 1887, became a center for the flourishing Chicano movement in the 1960s. It’s where activists organized around Robert F. Kennedy’s presidential campaign. It’s where leaders met to plan the East Los Angeles high school student walkouts protesting inequities in their schools as well as the historic Chicano Moratorium against the Vietnam War draft. Labor leader Cesar Chavez gave speeches in the church hall. In later years, the church played a role in helping Central American refugees fleeing wars.

The Church of the Epiphany, in the Lincoln Heights neighborhood of Los Angeles, recently earned a spot on the National Register of Historic Places. The church is known as a birthplace of the Chicano movement in the 1960s. Photographed on Thursday, Feb. 4, 2021. RNS photo by Alejandra Molina

RELATED: Mexican American religious life will be preserved in UCLA archive collection

Now, five decades later, the church has earned a spot on the National Register of Historic Places, the official list of sites worthy of preservation in the United States.

This designation is one of a few listings on the Register related to Chicano history. Of the roughly 86,000 designated sites, less than 8% were associated with African American, American Latino, Asian American and other minority groups in 2014, according to the Congressional Research Service. The church announced its recognition in late January.

“To have that place recognized for what it has done in the community is important,” Lopez said.

Lopez said the church was where she learned community organizing and “how to be there for the people.

“It was a very special place because it wasn’t conservative, but yet they had the gospel that said we had to act,” she added. “We had to be active on behalf of our brothers and sisters. That became home for me.”

An 1968 photo of the altar at Church of the Epiphany in Los Angeles. © La Raza Staff. From the La Raza Photograph Collection. Courtesy of the UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center.

The Rev. Tom Carey, vicar of Church of the Epiphany, said the church has remained relevant all these years.

“It has always been a place that has been at the forefront of social activism,” Carey said.

Epiphany has continued to hold Sunday services in Spanish and English online during the pandemic. It offers up its kitchen to prepare meals for delivery to local families and seniors. Clergy have partnered with other groups to address evictions and deportation arrests and have participated in Black Lives Matter protests and rallied for grocery workers demanding hazard pay.

To Carey, what makes a place sacred “is what has gone on there in the past” and “what continues to happen there.”

In announcing the national designation, the church has launched a GoFundMe initiative to raise $230,000 for a series of renovations. The fundraiser is part of the final phase of a $1 million “Restore Epiphany Campaign” to help fund the church’s preservation. The church has so far raised more than $780,000.

Funds are earmarked toward Epiphany’s leaking basement, which was home to the Chicano newspaper La Raza and stores photos and documentation of the church’s history. The money will also go toward protecting the archives, installing an elevator for ADA access, and creating meeting rooms for legal and health clinics. They also plan to update the heating and cooling systems.

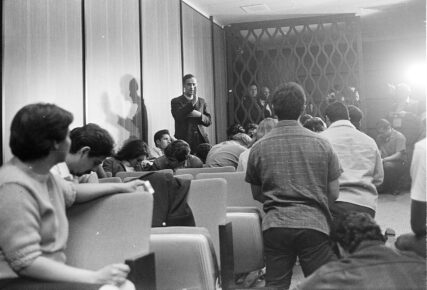

- Church of the Epiphany pastor John Luce appears to pray at a Los Angeles Unified School District (LAUSD) Board of Education meeting in 1968. © Devra Weber. From the La Raza Photograph Collection. Courtesy of the UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center.

- A service at Church of the Epiphany in Los Angeles in 1968. © La Raza Staff. From the La Raza Photograph Collection. Courtesy of the UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center.

“It’s an important moment to capture the important role of the church,” said Armando Vazquez-Ramos, who grew up in Lincoln Heights after emigrating from Mexico in 1961. “I hope to God it will continue to be an activist, community-minded church.”

While Vazquez-Ramos identifies as agnostic, Epiphany has played an important role in his life. He described the church as a “mecca” and a “birthplace” of the Chicano movement.

As a college student at Cal State Long Beach, he remembers attending meetings in the church’s basement to help his former high school teacher Sal Castro plan the student walkouts.

RELATED: 50 years later, Chicano Catholic activists recall their midnight Mass clash with police

Vazquez-Ramos’ own faith came into play at the height of the Chicano movement.

Raised Catholic in Mexico, he became disillusioned with the church in the U.S. where he said Masses were in Latin. He recognized inequities within the church and became an activist with Católicos por La Raza, a Catholic lay group formed by Mexican Americans in 1969.

Católicos por La Raza members demonstrate in Los Angeles, circa 1970. © La Raza Staff. From the La Raza Photograph Collection. Courtesy of the UCLA Chicano Studies Research Center.

The group called out the Catholic Church for its lack of involvement with the farmworker movement led by Chavez and a lack of support for the walkout movement. The group is known for its 1969 confrontation at St. Basil Catholic Church in L.A. where it clashed with police on Christmas Eve as its members tried to confront then-Cardinal James Francis McIntyre about what they said was the church’s neglect of the poor.

Fifty years later, Vazquez-Ramos helped organize a 2020 reunion of the now-disbanded Católicos por La Raza group to commemorate the famed demonstration. It was held at Epiphany.

To Vazquez-Ramos, many religious institutions are “about making money.”

“But here is the difference,” he said. “The Church of the Epiphany continues to be an institution committed to helping its community.”

The church’s recognition, Vazquez-Ramos said, is “historically important to our community because there are so many landmarks that are often ignored because they’re not part of the mainstream of America.”

- The Church of the Epiphany, in the Lincoln Heights neighborhood of Los Angeles, recently earned a spot on the National Register of Historic Places. The church is known as a birthplace of the Chicano movement in the 1960s. Photographed on Thursday, Feb. 4, 2021. RNS photo by Alejandra Molina

- The Church of the Epiphany, in the Lincoln Heights neighborhood of Los Angeles, recently earned a spot on the National Register of Historic Places. The church is known as a birthplace of the Chicano movement in the 1960s. Photographed on Thursday, Feb. 4, 2021. RNS photo by Alejandra Molina