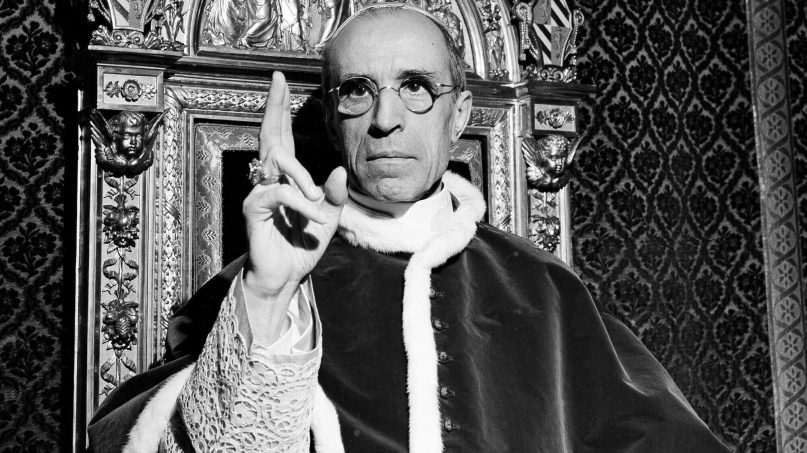

(RNS) — The debate about the late Pope Pius XII and the Holocaust — what he knew and why he did not openly denounce it — has been hotly contested for decades in articles, books and conferences. In Berlin, it’s now taken to the streets.

To one street, to be more precise. The Pacelliallee, a tree-lined boulevard in western Berlin, bears the name of Archbishop Eugenio Pacelli, the Vatican’s nuncio in Germany from 1917 to 1929 who later became Pope Pius XII.

The long-awaited opening of the Vatican archives from World War II last March, allowing the closest look yet at Pius’ diplomacy, has excited rival researchers sifting the files for a rationale for his relations with the Nazi regime: proof, in other words, that he was an outright anti-Semite, as some allege, a secret Germanophile or simply a cautious diplomat.

RELATED: German teens go to Israel to atone for their families’ Holocaust history

In Berlin, it has also injected street names into decades-long debate. In the anti-Pius camp are two historians, backed by Germany’s ombudsman for anti-Semitism, who last year asked Berlin authorities to strip Pius’ name from the Pacelliallee because he allegedly knew all about the Holocaust but failed to denounce it.

The petition by their “No-Pa Berlin” group has attracted about 1,100 signatures so far — about as many as have signed a counterpetition launched to defeat it.

Johan Ickx, a Belgian-born Vatican archivist, has now rallied the pro-Pius camp with a new book in Italy titled “Pio XII e gli Ebrei” (“Pius XII and the Jews”).

In it, he argues that the long-hidden files show how persecuted Jews from several occupied nations saw the controversial pontiff as their last, best hope for salvation.

This debate has gone on at least since at least 1963, when the stage play “The Deputy,” by the then-West German author Rolf Hochhuth, questioned Pius’ hitherto good reputation with accusations that he was indifferent to the Nazi slaughter of European Jews.

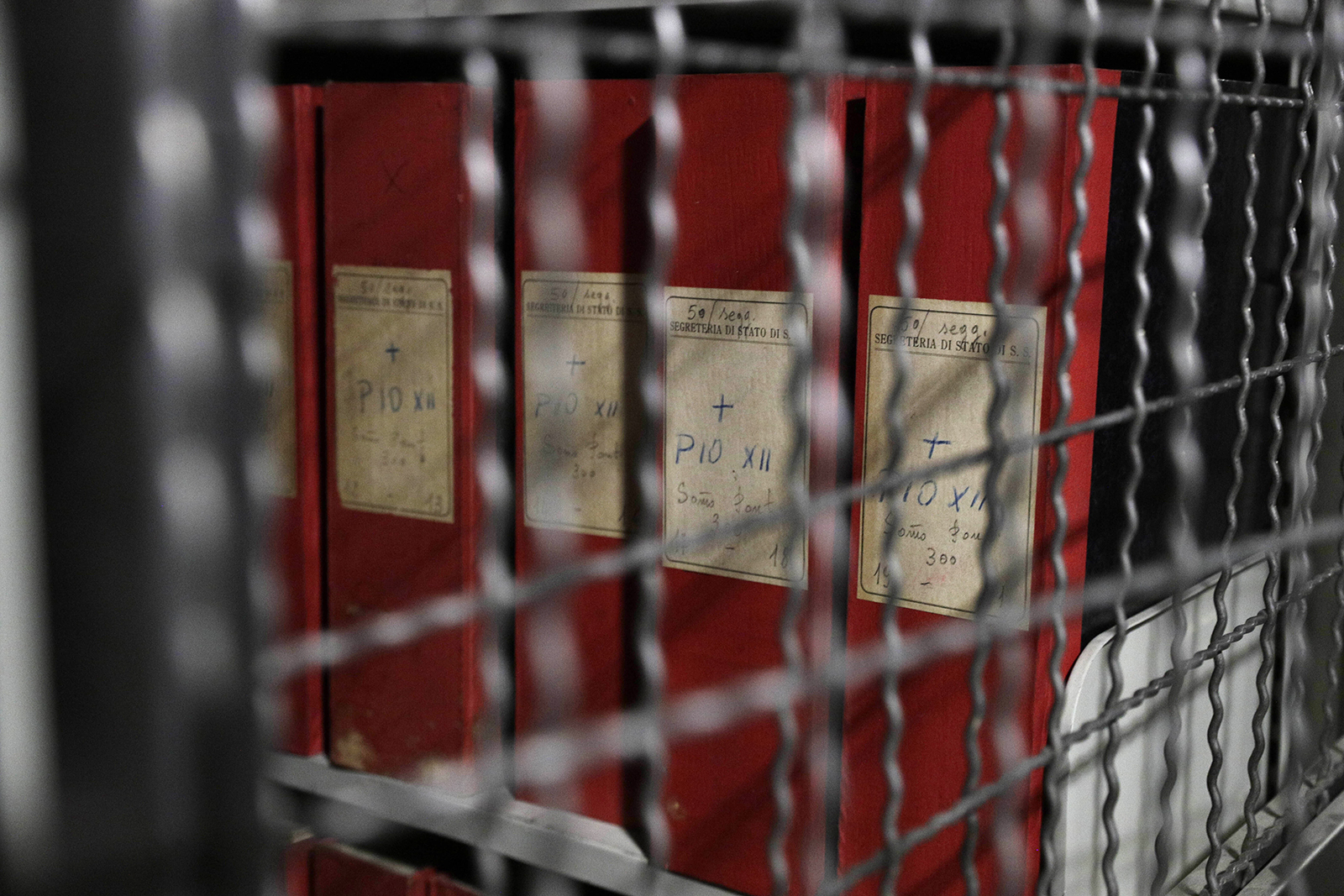

Folders marked with labels reading “Pius XII” are seen through a grating during a guided tour for media of the Vatican library on Pope Pius XII, at the Vatican, Feb. 27, 2020. The Vatican’s apostolic library on Pius, the World War II-era pope, and his record during the Holocaust opened to researchers on March 2, 2020. (AP Photo/Gregorio Borgia)

Opinions are so polarized that the Vatican’s wartime archives, which have offered up some anti-Pius evidence since they were opened last March, will probably not settle the debate.

The anti-Pius faction in Berlin seems to have gained the advantage with its proposal for a new person to honor. It wants to rename the Pacelliallee after Israel’s former prime minister Golda Meir.

“Pacelli spread anti-Semitic clichés for decades,” the petition launched by the two historians charges. “He made Hitler’s first foreign policy success possible in 1933.” The reference is to the Reichskonkordat, an agreement between the Third Reich and the Vatican, negotiated by Pacelli.

After the Second World War, it adds, his Vatican staff helped smuggle former Nazis such as Adolf Eichmann and Josef Mengele to exile in Latin America.

As many as one-third of the comfortable villas along today’s Pacelliallee were confiscated by the Nazis from their Jewish owners in the 1930s. “We consider it inappropriate to name such a crime scene after an anti-Semite,” the petition says.

Meir was an “ideal candidate” to replace Pacelli, it continues, because of her experiences as a refugee, trade unionist, Cabinet minister and the first woman leader of Israel.

The choice of pitting Meir against Pacelli is ironic. When Pius died in 1958, the American-born foreign minister of Israel joined other Jewish leaders in praising the late pope for raising his voice “in condemnation of the persecutors and in compassion for their victims.”

The Catholic Church, a small minority in traditionally Protestant Berlin, was quick to reject the proposal by historians Ralf Balke and Julien Reitzenstein. It was “simply not serious,” the Vatican nunciature said in a statement.

The conservative Catholic newspaper Die Tagespost accused Felix Klein, the government’s anti-Semitism ombudsman, of falling back on Soviet-era atheist propaganda for a Kulturkampf (culture war) against the church.

Ickx, the Vatican archivist, told the Italian weekly Famiglia Cristiana last month that the wartime archives were organized according to the countries the Holy See dealt with, except for a special file marked “Jews” that contained 2,800 letters pleading for help.

“I was very surprised,” he said in an interview. “I thought it was something fake, as if someone from the Vatican had thought afterwards of preparing an ad hoc dossier in defense of the role they played during the war for the Jews. But no, it was all authentic.”

For Ickx, this proved that Jews knew Pius was working behind the scenes to help them, “otherwise they wouldn’t have written.”

A car passes an intersection along the Pacelliallee, a tree-lined boulevard in western Berlin. Image courtesy of Google Maps

Renaming streets has a long tradition in Berlin. With centuries of history as capital of Prussia and then the German Reich, it has many streets and squares named for people or places once held in high esteem but now politically incorrect.

In the time it takes to change names, however — German bureaucracy demands detailed consultations — Berlin’s free-wheeling political atmosphere can generate some surprising suggestions.

One group has asked to change a street named after Martin Luther, the father of the Protestant Reformation, to honor Prista Frühbottin, who was burned as a witch in 1540. Luther, it said, had “sowed venomous hate” against minorities.

RELATED: Does anyone ‘own’ the Holocaust? An Orlando controversy inflames the issue

The debate about renaming central Berlin’s Mohrenstrasse got new support last year from the U.S. Black Lives Matter movement. “Mohr” is an old word for a dark-skinned person, and activists want to change this to honor Anton Wilhelm Amo, the first African to earn a German doctorate, in 1734.

Another group has asked its district authorities to name an intersection David Bowie Platz, after the glam rock star who once lived near there in the 1970s. One of their arguments is that another district has renamed a street after the musician Frank Zappa.

The name Golda Meir seems likely to eventually replace that of Pacelli, but possibly not for anything she did or he didn’t. Berliners think they have far too many public places honoring men and have been renaming more streets after women in recent years.