Source: Pixabay. https://pixabay.com/photos/book-bible-bible-study-open-bible-1209805/

(RNS) — “Read the Bible every day.”

A lot of Christians are told that reading the Bible is going to answer all of life’s problems and they should devote significant blocks of time to reading it.

But they’re less often taught how to read the Bible. Or at least, how to read the Bible so they have enough tools to understand its beauty, its problems and its contradictions. What we get from that ignorance are people who are quick to pretend that those contradictions don’t exist, and to wield the Bible as a weapon that just happens to support their point of view.

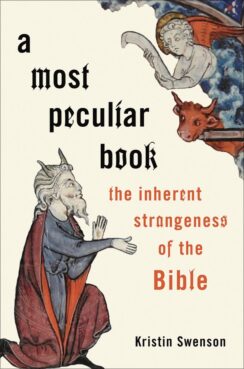

Kristin Swenson, a biblical scholar, writer and podcaster, can help with that. In A Most Peculiar Book: The Inherent Strangeness of the Bible, released this week from Oxford University Press, she gives readers a valuable “toolbox” for getting more out of the Bible. This interview has been edited for length and clarity. — JKR

Kristin Swenson, author of “A Most Peculiar Book”

RNS: Why this book?

Swenson: We tend to approach the Bible as a really clear, straightforward, linear narrative with pearls of wisdom and instruction that we can automatically apply to our lives. And a couple things happen when we start reading it more thoroughly and in depth. One is that we get confused! Because the Bible sometimes disagrees with itself.

We also run into passages that are frankly disturbing to our basic moral sensibilities, like capital punishment for offenses such as a child talking back or being rebellious within their family. That might strike a person today as overkill, pardon the pun. The Bible gives a rather clear directive to commit what we would call genocide. And that’s before we’ve gotten even halfway into the Bible!

With this book, I wanted to make space for people who are actually reading the Bible to reckon with the strange things they encounter that don’t fit that simplistic application. I wanted to give people tools to make sense of those things, or at least make peace with them.

RNS: Where do they start?

Swenson: First by realizing that the Bible, as a book itself, is strange. Understanding how it is strange as a book enables them to encounter the strangeness. The Bible isn’t only one book. It’s a collection. And that collection evolved over centuries, with contributions from people we don’t know. That is, some of the books are likely composites of different traditions, and texts that later editors then managed in ways that result in the books that we have.

It’s also strange in that all of it is really, really old to us. Even the latest texts of the Bible are ancient by an extraordinary measure to our modern sensibilities. And the languages through which we receive the texts are inaccessible to the vast majority of people. So people are reading translations, and any translation is itself a product of interpretation. It has to be.So one of the tools to pull out when we encounter texts that alarm us or don’t seem to make sense is to ask what other translations do with that text. And at least as important is knowing that the Bible came from a lot of different hands helps us to understand and accept where the Bible seems to disagree with itself.

RNS: Can you give an example of those disagreements?

RNS: Can you give an example of those disagreements?

Swenson: One of the most striking is a word-for-word disagreement that we find in the Hebrew prophets. Both Isaiah and Micah prophesy a time when “they shall beat their swords into plowshares, and their spears into pruning hooks.” Even to people who don’t read the Bible regularly, that text may be familiar, because it’s familiar as a text of peace, of the cessation of war. I love that text.

Unfortunately, in the book of Joel, which is also one of the Hebrew prophets in the Bible, we read of a time when they shall beat their plowshares into swords, and their pruning hooks into spears. It couldn’t be a more stunning disagreement.

And then let’s jump back to the beginning of the Bible—Genesis 1 through 3, where you have very different pictures of the beginnings of the world. Besides the strikingly different literary styles and images of God and names for God, you have clear disagreement about the order in which God created things. In Genesis 1, animals are created before humans. In Genesis 2 and 3, animals were created after them. And in the story of the flood, we have different reports of how many animals Noah took on to the ark.

If you don’t have that toolbox of knowing something about the Bible, and how it is strange as a book, then you might 1) undergo incredible gymnastics of logic to try to force the text to make the kind of sense you expect it to or 2) dismiss it as nonsense, because it can’t be authoritative if it disagrees with itself. But if you know that the Bible was written over a very long period of time, you have a toolbox for understanding how the texts might be different from each other.

RNS: You mention that believers sometimes misread the Bible. What are some of those misreadings today?

Swenson: Well, back to Genesis 1, that creation story in which a disembodied God elegantly creates the world in seven days. The creation of human beings includes this phrase that’s typically translated as “having dominion over the earth.” That passage has been misread to apply in our lives as permission, even a command, for the wholesale destruction of the planet. When you learn more about the Bible and what is strange about it as a book, you’ll conclude a very different directive to human beings—much more nuanced, and with clear command to take care of the earth.

RNS: What do you want readers to take away from your book?

Swenson: This is the work of a lifetime, to know how the Bible is strange. It isn’t as simple as “now I’m going to give you a handful of the secrets that everybody who knows them uses to make sense of the Bible,” even though I do give tools for that.

Beginning to learn about the Bible is to assume a posture of humility. It’s to pause when we encounter texts or directives that we know would cause another harm, or otherwise run counter to what we learn through other, I’ll say God-given, abilities—using our brains, for instance. Engaging in this lifetime of learning about the Bible, which is how the Bible is strange as a book, would give believers pause before declaring “God says this, therefore I will do this.” No matter what the “this” is—homophobia, genocide, capital punishment of the rebellious child, destruction of the earth, rejection of whole categories of people who are deemed to be lesser—learning what is strange about the Bible gives us some guardrails against committing offenses as human beings.

Related content:

You may be reading the Bible wrong. Pete Enns says the Bible itself shows a better way.