(RNS) — In my spare time, I am writing yet another installment of “The Cat in the Hat,” titled “The Cat in the Hat Comes Back Yet Again.”

You cannot say mean things out loud

You cannot say them in a crowd

Don’t even think it! Don’t say that!

Was the moral lesson of the cat in the hat.

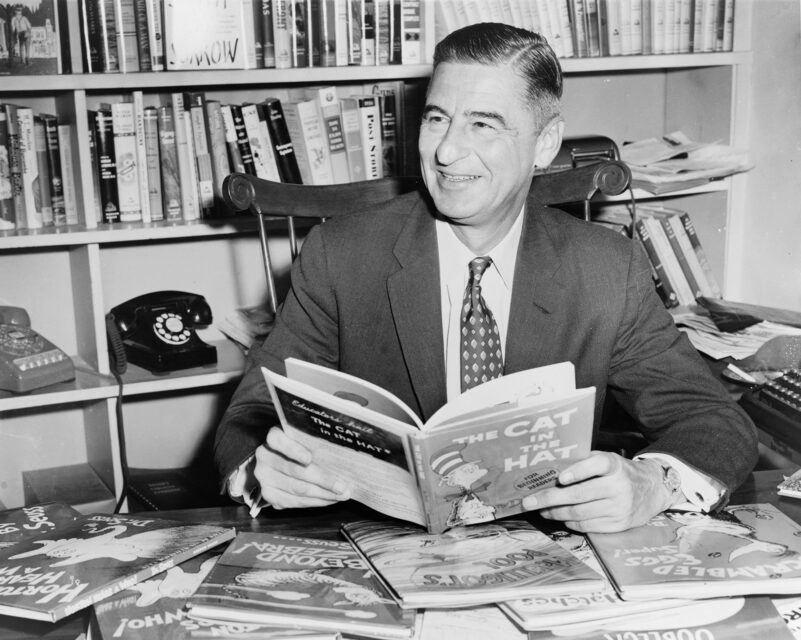

Not a few people snickered, and even moaned, upon hearing the announcement that certain Dr. Seuss books, such as “And To Think That I Saw It On Mulberry Street,” will no longer be available.

The reason? One example: “Mulberry Street” contained negative, stereotypical portrayals of Asians.

Conservatives are up in arms. Another example of “cancel culture,” they scream.

I have often criticized the manifestations of cancel culture in the United States.

On the left, it can mean loss of a job, social shunning and various kinds of nastiness.

The right, of course, has its own version of cancel culture. On Jan. 6, had Nancy Pelosi or Michael Pence been “canceled,” it would have been a permanent, lethal cancellation. As in the gallows that the miscreants had already erected.

But before we scream about this latest manifestation of the imagined priggishness of elite culture, let’s stop and breathe for a moment.

No one canceled these books by Dr. Seuss. The decision came from his estate. Those titles had not been selling well. Further: The estate has every right to protect the late, beloved author’s “brand.” In deciding that a creative decision that he made more than 80 years ago was no longer appropriate, the estate has determined that heirs can do teshuvah — long after the original deed has been done.

Jews should understand this.

More than this: We should empathize.

Consider some of the classic portrayals of Jews that are part of the cultural DNA of Western civilization.

Shylock, the moneylender in Shakespeare’s “The Merchant of Venice.” Shylock is one of the greatest roles in the history of theater, and one of the most controversial. In fact, the role is so powerful that the very name “Shylock” has become a negative term for a moneylender.

What makes the case of Shylock even more fascinating is that the character emerged at a time when there were, at least officially, no Jews in England. Did Shakespeare model Shylock after Christopher Marlowe’s “The Jew of Malta”? Did the Bard find inspiration in the case of a Marrano physician in England who was accused of conspiracy to murder Queen Elizabeth?

The jury — er, uh, the Jewry — is still out on both of those questions. But, quite often, when “The Merchant of Venice” is slated for performance, the controversy has a way of rising to the surface.

I will say that the best performance I have ever seen of “The Merchant of Venice” was about a decade ago in Lenox, Massachusetts. The production portrayed anti-Semitic graffiti on Shylock’s house, and it ended with Shylock chanting Kol Nidre, the iconic Yom Kippur statement of “pre-forgiveness” for not fulfilling vows.

Obviously, the director knew the (apocryphal) tradition that Spanish Jews forced to convert to Christianity would utter that statement as a way of proclaiming to God that their conversion was false. Since Shylock is forced to convert to Christianity, putting those words into his mouth — which was certainly not in the original play — was a stroke of theatrical brilliance.

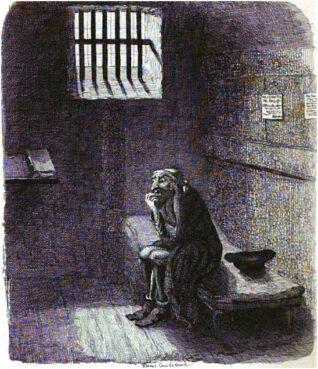

Fagin, the leader of the gang of pickpockets in “Oliver Twist” by Charles Dickens. The reader of this classic novel would have no doubt as to Fagin’s ethnicity; the story is littered by references to “the Jew” and “the old Jew.” Clearly, Dickens was relying on anti-Semitic stereotypes that existed in Victorian England. The original illustrations for “Oliver Twist” make it clear: Fagin is pure evil, rarely seen in light, but only in shadow, portrayed with a long, hooked nose.

The character Fagin from “Oliver Twist” (1838) by Charles Dickens. Image courtesy of Creative Commons

Quite telling and sobering: Whereas Shylock could convert to Christianity as atonement, by the time Dickens wrote “Oliver Twist,” more than 200 years later, no such atonement was available for Fagin. He must die — symbolic of the growing racial anti-Semitism that would brook no conversion to another faith, but that saw the Jew as evil in his or her very essence.

Also telling, and redemptive: By the time “Oliver Twist” became the ever-popular musical “Oliver!,” Fagin had become de-Judaized. Several generations of theatergoers, and kids who have put on “Oliver!” in school performances, would have had absolutely no idea that the original Fagin was a Jew.

Thank God.

“The Merchant of Venice” and “Oliver Twist” have been matters of controversy for years.

But there have been other literary portrayals of Jews that have somehow passed unseen through the moral metal detector.

For example, the character of Meyer Wolfsheim in “The Great Gatsby” by F. Scott Fitzgerald. He is described as a gambler who fixed the 1919 World Series — a clear allusion to Arnold Rothstein, a New York crime kingpin.

Wolfsheim has appeared in several movie versions of “Gatsby” — most recently, in a film adaptation starring Leonardo DiCaprio as Gatsby. In a few of them, he demonstrates stereotypical Jewish characteristics. His jewelry made of human molars is about as grisly a touch as you could imagine, and only reinforces the demonic portrayal of the Jew.

(Fitzgerald puts some horrific racist and nativist words into the mouth of Tom Buchanan — which have been both criticized in recent years, as well as held aloft as an example of an ideology that did not go out of style with the flappers.)

Do I think that we should ban “The Merchant of Venice,” “Oliver Twist” and “The Great Gatsby”?

Hardly. They are part of the literary inheritance of Western culture.

But I do believe that educators can, upon teaching those texts, put their bigotries into historical context. Teachers should use those texts as a way for the predominantly gentile world to come to grips with its all too extant heritage of Jew-hatred.

You can do that with older kids, and with adults.

Not so with Dr. Seuss’ audience — little children.

You might be upset with this kind of self-censorship. It might elicit a few groans from you. “Even Dr. Seuss! Is nothing and no one off-limits?” you might say to yourselves and to each other.

Yes, a few of his lesser titles bit the dust, and not the dust jacket. But this is a small price to pay for our society’s realization that we are all in the midst of a racial teshuvah.

As for me, I always loved “Green Eggs and Ham.” Sam I Am spends the book trying to persuade the narrator to try green eggs and ham — until he finally capitulates.

I always thought and taught that the book was an allegory about the forced assimilation of Jews.

You mean it’s not?