(RNS) — In the days following the death of George Floyd, Marc Dollinger was suddenly in demand everywhere.

In addition to teaching classes at San Francisco State University where he is full professor, the blond-haired historian of U.S. Judaism was suddenly sought after for his insights on the racial reckoning happening across the country and the role American Jews play in it.

In the middle of a pandemic and amid an intensity that hasn’t let up, Dollinger parked himself in front of his home computer and hasn’t left.

Since May, the 56-year-old professor has led 80 Zoom lectures and workshops, speaking to synagogue groups, college students and interfaith leaders. He’s been invited to talks at Jewish community centers, historical societies and book clubs. He was interviewed by the NFL and by CNN’s Don Lemon. He spoke to German public radio and to a Mormon-Jewish dialogue group.

The subject, as always, is Jews and race, or, more specifically, whether white U.S. Jews share the blame for America’s racial injustices. These are weighty themes, and he expounds on them with a ready smile and a folksy demeanor.

The nation’s racial reckoning has challenged his own biases, but in this age of polarization, Dollinger remains that rare public scholar who owns up to his own biases with disarming candor.

RELATED: American Jews are taking a hard look at racism in their midst

Marc Dollinger. Courtesy photo

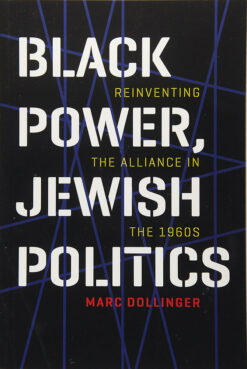

What draws people to Dollinger is a book he wrote in 2018 that challenged prevailing views of the Jewish civil rights activism of the 1960s. Late last year, his publisher, Brandeis University Press, saw it was running out of copies of “Black Power, Jewish Politics: Reinventing the Alliance in the 1960s” and offered to reprint it with a new preface.

Dollinger quickly penned a 2,400-word introduction that decried the near-exclusion of Jews of color from leadership in institutional Jewish life and expounded on the ways many Jews have benefitted from white supremacist structures.

Brandeis University Press objected to several passages and went ahead and reprinted the book without a new preface. (The press claimed it didn’t have time to work through the revision process, so it went ahead and printed it as is.)

The incident underscored the tensions and conflicting impulses among American Jews when it comes to race. On the one hand, they are among the most liberal constituents of American society. On the other hand, American Jews have often wanted to preserve their special status as a persecuted minority even as many have become part of white America.

“Much of our understanding of our American Jewish past is rooted in this notion that Jewishness is fundamentally different from whiteness,” said Dollinger. “My research says it’s both/and, not either/or. Jews are the most progressive white ethnic group in America. And it really helps to be white. American Jews need to reconcile they’re not as special and different and exceptional as they always thought they were.”

The ruckus over the preface has only boosted his cachet.

A Reform Jew from suburban Los Angeles, Dollinger grew up insulated from the growing conflicts between Blacks and Jews in urban areas. As a kid, he was obsessed with basketball and announced to his mother he wanted to be a Harlem Globetrotter, after seeing the team perform at Inglewood, California’s “Fabulous Forum.” He was disappointed when his mother explained that, as a white person, he couldn’t.

As an undergraduate student at the University of California, Berkeley, he was again disappointed when he reached out to a member of the African Student Union with a proposal to start a “Black-Jewish dialogue.” The ASU member, he recalled, burst out laughing.

Marc Dollinger, top left, participates in a virtual presentation with the JCRC of St. Louis in August 2020. Video screengrab

But the subject of race continued to captivate him, and, as a scholar of American Judaism, he found himself researching what is considered the heyday of Black-Jewish relations — the 1960s, when Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel marched alongside the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. from Selma to Montgomery and when two of the three civil rights workers killed in 1964 by the Ku Klux Klan in Neshoba County, Mississippi, were Jews: Michael Schwerner and Andrew Goodman.

What he found, however, burst whatever romantic notions he had about the short-lived interracial alliance. Southern Jews were far less invested in the civil rights struggle — in fact, they were mostly silent about it. And combing through archives, Dollinger discovered that even in the late 1950s, institutional Jewish leaders predicted the Black-Jewish alliance would end and Black anti-Semitism would grow. In a pragmatic turn, they actually encouraged the rise of the Black Power movement, which they adopted for their own purposes as Jews turned inward and embraced identity politics themselves. If Blacks can advocate for Blackness, the thinking went, Jews could advocate for Jewishness.

Dollinger’s book on the subject was well received in academic circles and in certain Jewish intellectual circles that had begun interrogating Jewish attitudes on race. It went through three printings.

But nothing could have prepared him for the intense new racial reckoning in the wake of George Floyd’s killing at the hands of Minneapolis police on May 25, 2020.

Suddenly he was in high demand as Jews began their own accounting of racism in America.

Marc Dollinger speaks during an online interview. Video screengrab

By this time, though, he had undergone his own racial reckoning. A Black Jewish friend he met occasionally for lunch challenged him, saying, “You wrote 200 pages about Blacks and Jews and not a single page about Black Jews.”

He had no good response. His interlocutor went on: “You used the phrase ‘Black-Jewish relations,'” she told him, but that phrase implies Jewish whiteness. “What if a person is both Black and Jewish?”

That conversation began a whole new reconsideration of his own identity and privilege as a white Jewish scholar, which he acknowledged in the draft of his preface, now posted to his website, saying, “Jews of Color have been erased from almost all of the historical literature in American Jewish history, this book included.”

He then went on to say that white Jews have enjoyed upward mobility and have tacitly, if not always consciously, benefitted from white supremacist structures.

That was too much for Brandeis Press. Editors at the press suggested he review how the words “white supremacy” and “erasure” were used and consider less “loaded” terms, according to emails between him and the press that he shared with a reporter.

“Black Power, Jewish Politics: Reinventing the Alliance in the 1960s” by Marc Dollinger. Courtesy image

Dollinger declined. At that point, Brandeis went ahead and reprinted the 2018 book without a preface. It then took the unusual step of releasing to Dollinger the rights for future printings.

“The concern was that there was no set up, no preparation, no explanation,” said Sylvia Fuks Fried, editorial director at Brandeis University Press. “There was no scholarly presentation of, ‘Here’s the situation, here’s what we’re looking at, here’s what we mean by these terms.’”

The dispute led to a backlash from scholars who insisted it was unheard of for prefaces to be subjected to such critiques and said the press violated a commitment to academic freedom.

“The role of scholarship is to use critical tools of research and interpretation to open conversations, not shut them down,” the scholars wrote in an open letter to the Forward.

But the incident also points to an unwillingness of some sectors of the Jewish community to recognize their complicity in institutional racism. Dollinger never claimed Jews were white supremacists. He suggested white supremacy was structurally embedded in such sectors as housing and education in ways white Jews have benefitted from.

“For people who push back, there’s a kind of response that it’s disrespectful to minimize the efforts Jews have gone to to succeed,” said Cheryl Greenberg, professor of history at Trinity College in Hartford, Connecticut. “Any acknowledgment we got a boost undermines that story.”

For others, said Greenberg, there’s a more judgmental tone: I made it, why can’t you?

Dollinger now realizes this self-reflection is challenging his role as the dispassionate historian he was trained to be. But he’s all-in for the ride. Civil rights is his life’s interest, and he feels a moral conviction to press on.

“I have an obligation to center the voices of Black Jews,” he said. “I missed a lot of big stuff. It feels good to be able to contribute to an important conversation.”

Dollinger is donating any honoraria from his many Zoom lectures and workshops to San Francisco State University’s HOPE Crisis Fund, which offers emergency assistance to students affected by COVID-19.

As for getting him to speak, he’s booked until late May.

READ: ‘Til Kingdom Come’ examines link between end-times theology and Israel politics