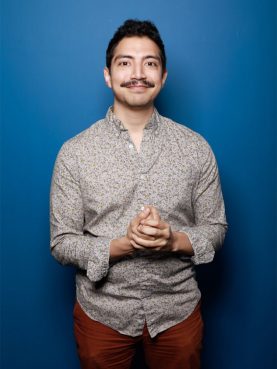

(RNS) — For the past three years, Eder Díaz Santillan has hosted a podcast on which he interviews LGBTQ people on how they’ve coped with their gender and sexual identities while being raised in traditional Catholic upbringings. He also openly discusses his own identity as a Latino and gay Catholic man.

To Santillan, being gay and Catholic has meant reconciling with the reality the church has never fully accepted his LGBTQ identity. However, he’s recognized there’s a difference between his own relationship with God and the priests who have condemned homosexuality from the altar. It took years, but Santillan realized he could maintain his faith and his LGBTQ identity.

That’s why it may have been a surprise to his listeners when he announced in mid-March he would no longer identify as Catholic. The announcement came just days after the Vatican’s decree it wouldn’t allow priests to bless same-sex unions, saying “God cannot bless sin.”

“It took me this long to recognize that I can let go of anything that hurts me,” said Santillan, 35, on Instagram.

RELATED: Pope Francis shuts down proposals to bless same-sex couples

Pope Francis’ rejection of proposals that would allow priests to bless same-sex couples has left many LGBTQ Catholics feeling disappointed and demoralized by an institution they felt recently represented a softening toward LGBTQ marriages within the church. As a result, some have decided to leave their Catholic identities behind, while others remain hopeful the church will eventually become more accepting. Though some have said Francis later distanced himself from that decision, some, like Santillan, say “that’s not enough.”

After the Vatican’s statement, Santillan felt an urgent need to break from his Catholic identity. He realized he could no longer “normalize being Catholic and gay to my audience,” adding that he had become accustomed to the church’s “condemning narrative.”

The fact the church would not bless same-sex unions was nothing new to Santillan, but what struck him was the Vatican felt the need to “be so explicit” about it.

“It was shocking,” he said.

Eder Díaz Santillan hosts the bilingual podcast “De Pueblo Católico & Gay,” where he openly discusses his identity as a Latino and gay Catholic man. Courtesy photo

To Santillan, the church’s stance is more than just an opinion of what is right and wrong; it fuels faith-based conversion therapy and the backing of laws that discriminate and criminalize LGBTQ people in Latin American countries. It has repercussions, he said. The Vatican’s “God cannot bless sin” statement took him back to his childhood, when he considered himself a sin due to the church’s rhetoric. He feared he was going to hell.

While Santillan figures out what it means to no longer identify as a Catholic, he said, he will always work to help those “who like me have to live with the trauma of the Catholic Church.”

RELATED: How a podcast is helping this Catholic and gay Latino man break the stigma

Since the Vatican’s declaration over same-sex unions, the Rev. James Martin, an American Jesuit priest, said he’s heard from a number of LGBTQ Catholics whose reactions have “ranged from anger to hurt to frustration to disgust to despair.”

He said about a dozen have explicitly told him they were leaving the church as a result.

“Among that group the general response was, ‘I’m done.’ Or ‘This was the last straw,’” Martin told Religion News Service via email.

“The main reason that LGBTQ people felt hurt was not simply that priests were forbidden from blessing same-sex unions, a decision that many people may have expected, but that the statement went beyond that and talked about their love as ‘sin,’” said Martin, an advocate of the LGBTQ community.

As he listens to LGBTQ Catholics, Martin said he reminds them “they are, by virtue of the sacrament of baptism, as much a part of the church as their pastor, their bishop or the Pope.”

He also invites LGBTQ people to see the church “in its totality,” noting Francis’ appointment of Juan Carlos Cruz, an openly gay man, to a papal commission, as well as the number of European bishops who criticized the Vatican’s language.

“I invite them to see themselves as full members of the church, even a church that seems not to know how to welcome them,” Martin said.

RELATED: Pope Francis voices support of civil unions for LGBTQ couples in new documentary

For queer Catholics like Xorje Olivares, 32, it’s about making individual choices around what their Catholicism looks like. Spirituality, he said, doesn’t need to be a “one size fits all.”

Xorje Olivares. Courtesy photo

“Everybody’s journey toward their acceptance of the Catholic faith or the role of the Catholic Church in their lives is their own, very much like everyone’s journey to their queerness is their own,” Olivares said.

Olivares, a former altar boy, hosts the podcast “Queer I am, Lord,” where he talks with LGBTQ Catholics about why they’ve stayed in or left the church.

While Olivares said many queer Catholics grew up conditioned to fear God and to believe they are going to hell, “we’ve gone past that.” Meanwhile, he also acknowledged many still find it difficult figuring out “what to believe, when they have a church saying one thing and their bodies telling them another.”

“I sympathize with their struggles because those are very real,” he said.

Olivares often thinks about the kind of message they would send to the Catholic institution if every single LGBTQ person decided to leave the church, but he remains grounded by the Bible verse “knock and the door shall be open to you.”

“Here I am, me and all my queer friends. We’ve been knocking on the door over, and over, and over again, and I would be so upset with myself if the door finally opens and the church becomes a little more welcoming, and I’m not there because I decided to walk away,” he said.

“I don’t know if the church will be the safe space that I need it to be, or if it ever will be, but I know that I still find some joy referring to myself as a Catholic,” Olivares said.