WASHINGTON (RNS) — When Vice President Kamala Harris’ office reached out to Eric Lander, the new director of the White House Office of Science and Technology Policy, to ask what book he planned to use during his swearing-in ceremony on Wednesday (June 2), he was stumped.

“I confess I had not thought about the question until they asked,” Lander told Religion News Service. “But once they asked, I had to think deeply about it, because when you choose a text you’re choosing values, or history, or other meaningful things.”

The question, he explained, made him think about the choice as “a statement of what’s in my mind and what’s in my heart” as he approaches his new role.

That choice set the scientist-turned-Cabinet official, who was confirmed by the Senate last week, off on a frantic evening of rigorous research that would eventually lead him to the Library of Congress and an obscure, recently rediscovered 500-year-old printing of a well-known Jewish text.

The MIT and Harvard biology professor and geneticist began his search by convening a Zoom confab with his wife and children, who helped point him to a value from Lander’s Jewish tradition: Tikkun olam, Hebrew for “repair the world.”

Lander, who also served as co-chair of former President Barack Obama’s Council of Advisors on Science and Technology, said he attends Jewish services but that his own Judaism is “complicated to describe.”

Suffice it to say that “the traditions — the ethical traditions — everything that comes from that faith and the faith I still practice in some ways, they matter a lot to who you are,” he said.

RELATED: Joe Biden’s family Bible anchors faith-infused inaugural events

His family picked up on a similar sentiment. “The minute we realized the question was values, we all went to tikkun olam,” Lander said, explaining that tikkun olam has particular resonance in his family: “What is our purpose here? Our purpose is to repair the world, to help others in need of help, to take in strangers, to have empathy.”

That realization, in turn, reminded Lander of an expression found in the Mishnah, the earliest collections of rabbinic interpretations of oral Jewish law: “It’s not required that you complete the work, but neither may you refrain from it.”

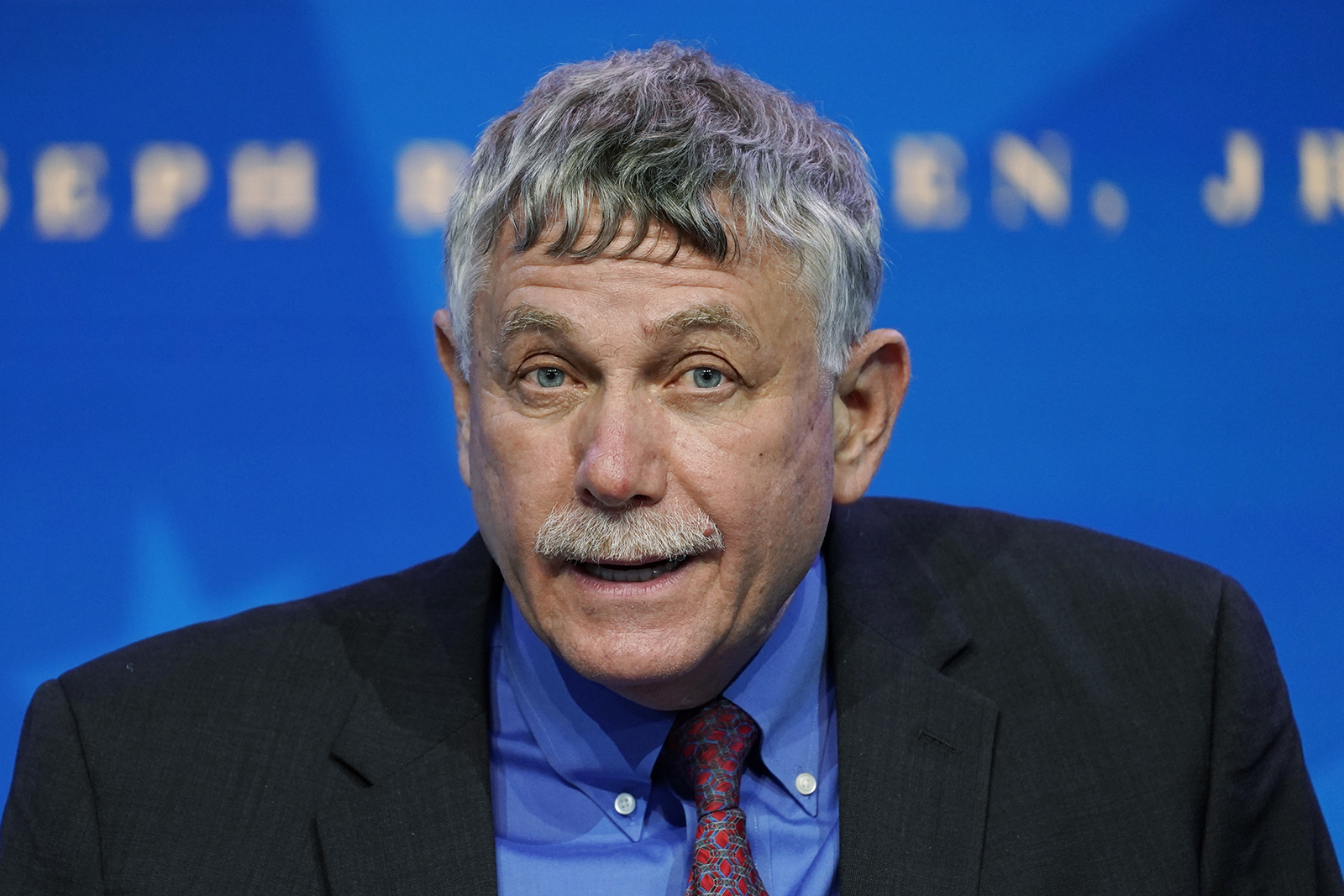

In this Jan. 16, 2021, file photo, Eric Lander speaks during an event at The Queen theater in Wilmington, Delaware. (AP Photo/Matt Slocum)

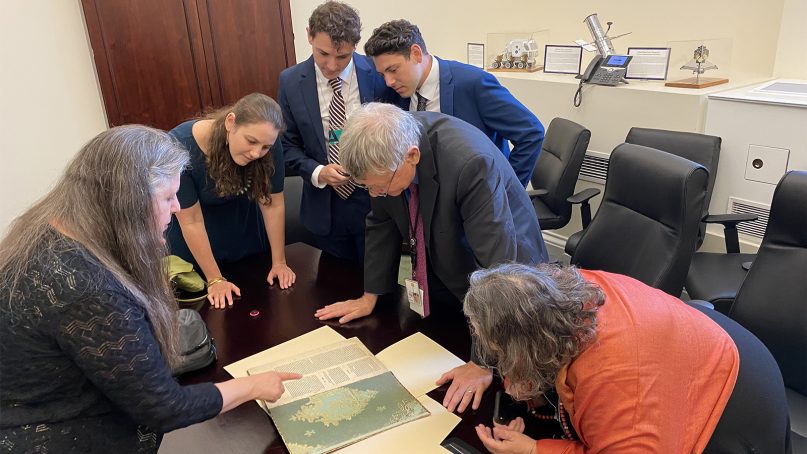

In scouring the Library of Congress catalog for a copy of Mishnah, however, Lander stumbled upon something a bit more specific: a 13-page volume containing the Pirkei Avot, a subset of the Mishnah that focuses on ethics and contains the expression.

Lander couldn’t help but notice the publication date: 1492, an era when Jewish populations were expelled from the Kingdom of Spain. He’d later learn the book was produced by a Jewish printer in Naples, whose history was entangled with Spain at the time: The kingdoms were ruled by men who shared a family connection and a name — Ferdinand.

While one Ferdinand is known for setting in motion the Spanish Inquisition, the other (in Naples) was more tolerant and accepted Jewish refugees.

In listening to that history, Lander heard a lesson for modern ears.

“The world has experimented with intolerance, with the view that everybody has to think like I think, worship like I worship,” he said. “(But) the world experimented in 1492 with tolerance — with the idea that we would have a diversity of people and perspectives. I think the lessons of the 1492 era are lessons for today: coming together and making our diversity an incredible asset for this country going forward.”

Ann Brener, a specialist at the Library of Congress who helped Lander with his request, is well acquainted with the book and its peculiar history. “This book that Dr. Lander found was only inches away from not being cataloged at all,” she said in an interview.

Brener stumbled upon the volume a decade ago while working with a collection of some 40,000 uncataloged rabbinic texts, most from the 19th and early 20th centuries. In the course of her work, she examined a thin publication that didn’t look altogether different from others: a large, folio-sized book with a flimsy binding lined with what looked like Victorian wallpaper.

But when she examined its pages, she realized she’d found something special.

“When I touched this paper, I knew immediately … that I was touching something very ancient — none of this 19th century stuff,” she said.

Even then, the work wasn’t made available for people such as Lander to find online until a few months ago. Technically, it’s still not fully cataloged: Brener said it can only be located virtually because Dave Reser, a colleague at the Library of Congress, found a way to insert information from PDFs of research documents that included a record of the book’s existence into the searchable online catalog.

“Sheer magic,” Brener said in a follow-up email.

RELATED: Health experts, faith leaders and White House target the ‘movable’ on vaccines

But placing a record of a book online isn’t the same as making it easy to find or procure, and Brener was impressed Lander tracked it down.

“Dr. Lander acted like a true scholar: He went into the catalog, he did research, he found something that caught its eye,” she said. “That’s what we always hope for in our leaders and, frankly, seldom find.”

Lander said that in his job advising the president, he hopes his example will illuminate how research — especially scientific research — can achieve the values behind tikkun olam, something he suggested is illustrated by the ongoing pandemic.

“Being able to care for the afflicted, help people avoid illness, recover from the illness — this is an element of repairing the world,” he said.

Lander has some experience with intersections of religion and science: In 2020, he was appointed to the Vatican’s Pontifical Academy of Sciences. He also rejects the idea that religion and science are fundamentally opposed to each other.

“I don’t see why they should be incongruous with each other,” he said, arguing that “disagreements over facts” between faith leaders and scientists are the “least interesting” areas of discourse between the two.

He sees potential for future science-informed partnerships between the government and faith communities to tackle the pandemic — such as ongoing involvement of faith groups in vaccine distribution — or helping stem the impact of climate change.

“What really matters is values, and in that I find much less incongruity,” he said. “We are all trying to make the world better, make people feel better, give them comfort in the world.”

At the very least, both Lander and Brener hinted that using a 500-year-old Pirkei Avot to take the oath of office may serve as a reminder of an early — and enduring — collaboration between religion, technology and science: using a printing press to reproduce sacred texts.

“In Hebrew, when you publish something, the term is to go out into the light — it’s a biblical phrase,” Brener said. “(The book) went out into the light in Naples in 1492, but Dr. Lander is letting it go out into light for a second time, and I couldn’t be more thrilled with that.”