(RNS) — Seven months after the tumultuous 2020 presidential election concluded, Republican hopefuls are already lining up for the 2024 nomination. Beyond former President Donald Trump himself, the ever-growing list of candidates includes a litany of Trump administration stars, including former Vice President Mike Pence and former Secretary of State Mike Pompeo.

Pence and Pompeo share a reason for their presence on this list: Each has spent years cultivating a public image as a champion of conservative Christians, particularly the white evangelical community, which is still the most reliable portion of the Republican base.

Catering to the white evangelicals and other conservative Christians may be good politics, but the approach Pence, Pompeo and other prominent Trumpites such as Steve Bannon take to religion and public life is both bad for the country and bad for faith. By promoting an ideology of Christian nationalism, they propagate a narrow and dangerous vision for America that threatens to replace our diverse, pluralistic democracy with a kind of theocracy in which the separation of church and state is eroded and Christianity is politicized.

RELATED: The true Republican religion

Fundamentally, it’s a worldview that excludes the majority of Americans and amplifies an “us” versus “them” dynamic that divides us and creates fertile ground for discrimination and persecution. Its fix for a supposed moral decline is to restore Christian norms and dominance in social, cultural and political spheres.

Pence, who describes himself as “a Christian, a conservative and a Republican, in that order,” has often harped on America’s moral deterioration and the centrality of Christianity in solving the nation’s problems. During a 2018 address in Indiana, Pence noted: “We’ve come to a pivotal moment in the life of this country. It’s a good time to pray for America. If (God’s) people who are called by his name will humble themselves and pray, he’ll hear from heaven, and he’ll heal this land!”

Bannon is a little more explicit in connecting the dots of white Christian nationalism. Addressing an audience of conservative faith leaders at the Vatican in 2014, he noted: “I think strong countries and strong nationalist movements in countries make strong neighbors. That is really the building blocks that built Western Europe and the United States, and I think it’s what can see us forward.”

Shortly after leaving the White House in 2017, Bannon remarked to the Economist: “I want the world to look back in 100 years and say, their mercantilist, Confucian system lost. The Judeo-Christian liberal West won.”

By portraying the United States as a Christian nation locked in battle with foreigners and non-Christians, these prominent Trump administration alums inspire the same white Christian nationalists who led the Jan. 6 assault on the Capitol. The similarities between what Pence, Bannon and others have said and the “Great Replacement” or “white genocide” theory propagated by avowed white supremacists are startling.

White Christian nationalism presents a blinkered version of Christianity that downplays or outright ignores the key gospel lessons of charity, forgiveness and humility while minimizing or even rejecting key elements of American history. It overlooks contributions made by immigrants and it pushes away the enduring impacts of slavery and segregation on racial inequality.

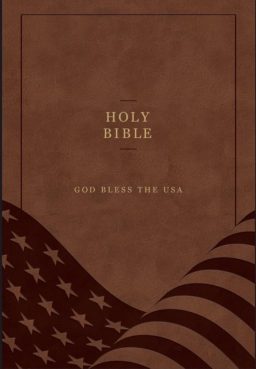

The pervasiveness of Christian nationalism is also underestimated. I recently joined fellow authors who have worked with the publisher HarperCollins to denounce plans by its subsidiary Zondervan to release a “God Bless the USA” Bible in which a copy of the Constitution, Bill of Rights, Declaration of Independence and Pledge of Allegiance will appear alongside the Old Testament and New Testament.

When we contacted Zondervan’s leaders, they expressed regret in signing the deal to publish the nationalist Bible and said they had not realized its implications. Even some of those involved in the propagation of Christian nationalism aren’t fully aware of their role in spreading the ideology.

Ironically, blurring the lines between religion and politics also ends up harming religion itself. History is littered with examples of Christianity, Islam, Judaism and other faiths being used as a cloak of legitimacy to justify and excuse abhorrent, destructive public policies. This is what links the Jan. 6 Capitol insurrection to Israeli settler violence in the West Bank, to the role of the evangelical church in Nazi Germany, to the Taliban’s puritanical rule in Afghanistan and to Buddhist persecution of the Rohingya minority in Myanmar.

Political scientist and philosopher Alexis de Tocqueville — often cited by conservative political theorists — both revered the religiosity of Americans and strongly advocated for the separation of church and state. He argued that tying religion too closely to government risked discrediting religion itself, as all governments become unpopular with time. In Mark’s Gospel in the New Testament, a statement attributed to Jesus promotes the separation of church and state: “Render unto Caesar the things that are Caesar’s, and unto God the things that are God’s.”

You won’t hear that passage from Pompeo on the campaign trail. In 2015 he launched a God and Country Rally with the declaration, “To worship our Lord and celebrate our nation at the same place is not only our right, it is our duty.” He has since made countless remarks citing evangelical theology as a powerful motivating force in his policymaking and denouncing government efforts to “rip faith from our schools.”

Ironically, perhaps, there are in part fewer practicing Christians in America today because Christianity is increasingly associated with the narrow, dogmatic and intolerant political ideology of people like Pence, Bannon and Pompeo.

In 2020, I led a bus tour aimed at inspiring voters of faith to make the common good, not political party, the determining factor in casting their 2020 presidential election ballots. Alongside members of Vote Common Good, I traveled more than 20,000 miles to host more than 90 rallies and roundtable discussions in 41 states. I met with thousands of evangelical voters, and many told me they had begun to question their faith after seeing Trump co-opt Christianity to further his America First agenda.

More recently, we saw Southern Baptist Convention messengers reject a challenge from the right and elect new President Ed Litton, a pastor who has spent decades working to bridge racial divides. Their commitment to racial reconciliation provides further proof that Christian nationalism does not resonate with all evangelicals.

The answer is not that religion has no place in politics. Politicians on both sides of the aisle often capitalize on their religious beliefs to win support. But leaders need to reframe how they express their faith in politics by using their religious values to inform policies that serve the common good.

It is possible for religion to serve an appropriate role in politics when it seeks to uplift the common good, rather than just the religion’s adherents. The important if subtle distinction is between using the institution of government to advance religion and allowing religious values to inform one’s individual approach to governing.

For the sake of the country and for the sake of religion, we need leaders who appreciate this distinction.

(Doug Pagitt is an American evangelical pastor, social activist, author and executive director of Vote Common Good, a group that works to inspire, energize and mobilize people of faith to make the common good their voting criterion. The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily reflect those of Religion News Service.)