(RNS) — Few periods were as critical to the development of Judaism and Christianity as the 100 years before and after the birth of Jesus.

Those were roughly the years governed by the Herods, the dynastic royal family that controlled Judea, the region surrounding Jerusalem, as well as the northern stretch once known as the kingdom of Israel, on behalf of Rome.

While most historians turn their lens on the religious ferment of that period, during which the Jerusalem Temple reached its apex in magnitude, the Herods themselves are often backstage actors to the larger drama.

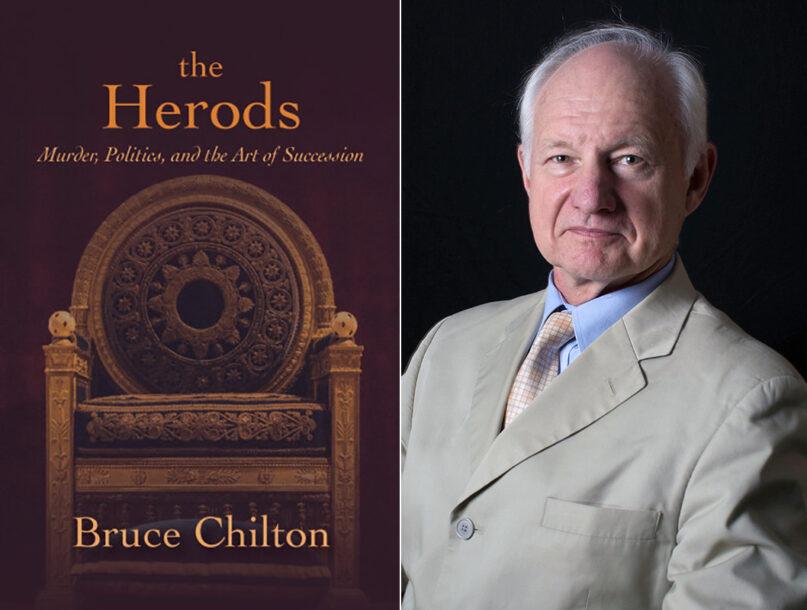

In his new book, “The Herods: Murder, Politics, and the Art of Succession,” Bruce Chilton, a professor of religion at Bard College, places the dynastic family front and center. (His main source is Josephus, a Jewish historian who chronicled the era while living in Rome.)

As the subtitle of the book suggests, there’s plenty of intrigue, Game of Thrones-style exploits and a supporting cast of big-name notables: Julius Caesar, Anthony, Cleopatra and Caligula, to name a few.

Chilton, who has written popular biographies of Jesus, Paul, Mary and James, both knows his stuff and guides lay people through a manageable narrative.

RELATED: Film series ‘The Chosen’ explores its Catholic side in the Eternal City

But he also hints at a more complex story, delving into the fraught relations between various groups of early Jews, their insistence on maintaining Temple practices and their understanding of divine rule amid changing political dynamics. Modern Judaism and Christianity were both formed in the crucible of those dynamics.

Herod’s ancestors were from the Edomite kingdom, called Idumea by the Greeks, in what is now southwestern Jordan. They converted to Judaism under the rule of the Maccabees (sometimes called the Hasmoneans) during a period of Jewish independence from 140 B.C. to 37 B.C.

But after the Roman conquest, the Roman Senate chose Herod’s father, Antipater, as its administrator in the region. Herod, Antipater’s second son, had — like his father, siblings, children and grandchildren — twin loyalties: to Judaism and to Rome. How they navigated between them is the subject of the book.

Religion News Service spoke to Chilton about his book, the rise of Christianity as a response to the political arrangements of the day, and about empire and theocracy. The interview was edited for length and clarity.

You present two views of Herod: a terribly volatile, violent and cruel man who killed his own Jewish wife and children and executed scores of others. On the other hand, he allowed Jewish practices at the Temple in Jerusalem to continue.

In the scheme of things, Herod the Great was very concerned with the public position of Judaism. He more than any other person was responsible for building the Second Temple, whose remains are still present. He was also extremely adept at negotiating the position of the practice of Judaism in the Roman Empire, (securing) the right of Jews living anywhere in the empire to be exempt from the requirement of offering sacrifice to the gods of Rome. Without that, the way in which Judaism thrived within the Roman Empire would not have been possible.

His grandson, Agrippa I, was a pivotal figure in convincing the later emperor, Caligula, to give up his completely insane project to build a statue of himself in the middle of the Temple. Agrippa directly interceded with the emperor, at risk to himself, and managed to prevail. However you judge these figures, they pursued their understanding of Judaism at some personal risk.

Was Herod considered fully Jewish?

Herod was born to a father who himself served the Maccabees. He was circumcised by the eighth day and understood himself to be a Jew. At the same time, he was presented to the Roman Senate amid sacrifices commonly practiced in the ancient world that were not in keeping with the Torah. If you were going to be a king in this period you would run into practices counter to the law of Moses. I myself hold to the view that Herod should definitely be described as being a Jew, but the definition of Judaism during this period was wider than imagined.

Was he accepted as a Jew by the Judeans?

He was, but he was not descended from the line of David. He had no real claim to the throne of Israel. There was, of course, opposition to any kind of rule apart from Davidic as not being legitimate. He also arrogated to himself the power to name high priests.

Jesus, who grew up when Herod’s son Antipas governed the Galilee, was highly critical of Herodian government. What was exactly his view?

Jesus was a disciple of John the Baptist, who was killed by Antipas. Jesus believed the only power that really mattered was divine. He made fun of Antipas and inflamed the tension between them. That’s why Jesus went on the move in and about Galilee and finally went to Jerusalem, which was under the control of Pontius Pilate, the Roman administrator. Pilate was famously antisemitic. The question then emerged: Should the legitimacy of the Romans be acknowledged? Should we pay the tax or not? Jesus said you can give what Caesar expects from what he himself provides, but that’s the extent of it. You cannot owe (Caesar) what God has produced.

The Apostle Paul had a more accommodationist attitude, right?

That’s right. Paul wanted to get along with the Romans and expected to get along with the empire. In the epistle to the Romans, he argues for obedience to rulers who are, in his time, Roman. Those same rulers ultimately arrested him and he finally died as a result of their legal system. During his imprisonment there’s a shift in his attitude toward political authority. Writing to the Philippians, he says our citizenship is in heaven. He comes to a view much more like that of Jesus in relation to Pontius Pilate.

Who else challenged Roman authority?

Herod had to deal with a man named Hezekiah, a leader described by Josephus as an archcriminal. Herod killed Hezekiah, but it was clear he had supporters in Jerusalem who believed there was an alternative to Roman rule, and who used the same phrase Jesus used — “the kingdom of God.” There were strong movements, not only in Galilee but elsewhere, that did not see Roman rule as inevitable. The Romans had only occupied Judea in 63 B.C., so belief that there might be a completely different order was not outlandish. They might have thought, we have survived Persians, Babylonians, Assyrians and Egyptians. Why not mount an alternative to Rome?

Does religion always accompany times of political ferment?

Josephus claims that theocracy is a particular characteristic of Judaism. But that doesn’t work out. The Romans clearly believed they were governing on the basis of divine authority. They saw emperors as being quasi-divine or actually divine. Human government is often a negotiation over how divine power is reflected in human governance and also what the instruments of that governance should be. It is not reasonable to suppose that people are all going to suspend their religious ideas in order to be governed in a just manner. Rather, it’s the reverse: How do they negotiate their religious ideas in such a way that the government attracts their commitment and they can live justly with people who differ from them?

RELATED: Orlando’s Holy Land theme park sold by TBN to health care company