(RNS) — Ask flutists to name the greatest pieces for their instrument and high on the list will be Johann Sebastian Bach’s “Sonata in B minor” for flute and keyboard. Now believed to have been written around 1735 for performance by Leipzig’s Collegium Musicum, which Bach directed, it is a secular composition in a strong spiritual vein.

The long opening Andante movement has the depth and feel of the opening choruses of the composer’s St. John and St. Matthew Passions. The sweet and stately middle movement could easily be a soprano aria from one of his church cantatas.

And then there’s the up-tempo finale. Marked “presto,” it consists of a brisk three-part fugue followed by a wildly syncopated jig (or, in the French orthography employed by baroque composers, gigue).

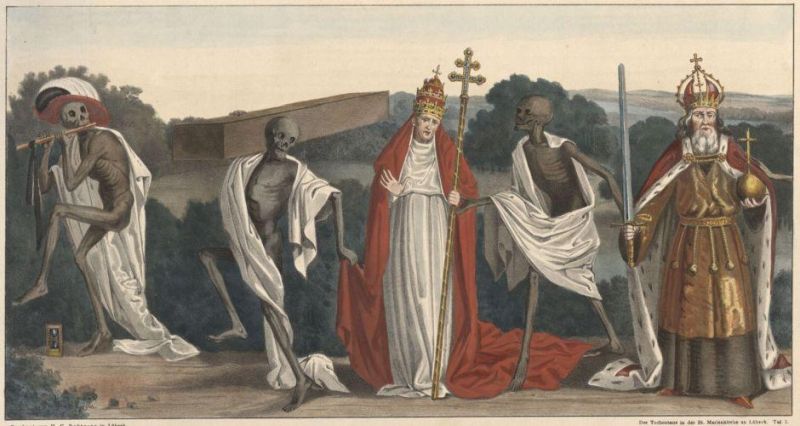

Preparing to perform the sonata last week with our college’s brilliant young organist Christopher Houlihan, I began to feel this jig was a Totentanz, one of those dances of death portrayed in late Renaissance and early modern prints. Could Bach have intended a musical version?

The most famous such renditions are Listz’s “Totentanz” (1849) and Saint-Saëns’ “Danse macabre” (1874), but the only pre-19th-century example I can find is “Mattasin oder Toden Tanz,” from a collection of instrumental pieces by the Dresden court composer August Nörmiger published in 1598.

Be that as it may, Bach could have been inspired to compose a Totentanz as the result of the trip he made to Lübeck in 1705 to learn from the great Danish organist Dieterich Buxtehude. Buxtehude’s position was at the city’s huge Marienkirche, which happened to possess a famous organ called the Totentanzorgel because of the no less famous late-medieval Totentanz painting that adorned the chapel where it was located.

So faded had the painting and the poems inscribed beneath the depicted figures become that the work was redone in 1701. Although both painting and organ were destroyed in an Allied bombing run in 1942, many photos of them survive. As you can see from the image above, the dance is led by a skeletal Death playing the flute!

The new poem, by Nathanael Schlott, puts Death’s message this way (in translation):

Come, you mortals, the glass is empty, come,

From the highest in the world to the peasant.

The road’s free of charge, so are all complaints,

You must venture a dance to my pipe.

So take a listen to this recording of the Bach “Sonata in B minor” by Marten Root and Menno van Delft of the Netherlands Bach Society and see what you think of my theory.

And meanwhile, Happy Halloween!