(RNS) — An often-forgotten detail in the Christian story of the Crucifixion is that Jesus did not just die; he went to hell. While the Gospels merely place him in a tomb, the fifth-century Apostle’s Creed notes that he “descended to the dead.” Medieval art abounds with images of this sojourn, known as “Harrowing of Hell,” in which Christ is shown freeing the damned from a Dantean inferno. The scene connects the ancient saga of faith to even older tales: Orpheus, Aeneas, Hercules and Odysseus all visited Hades only to return transformed.

To that long list of mythic depictions of the underworld we can apparently now add a 10-minute pop song about dating Jake Gyllenhaal.

Taylor Swift’s rolling release this month of various extended versions of her 2012 breakup ballad “All Too Well” has inspired a torrent of commentary about memory, loss, misplaced scarves, maple lattes and the long-ago relationship rumored to be at the heart of it all, a three-month romance between the singer and an actor nine years her senior.

In its various iterations — which so far include the original and revised album tracks, an accompanying short film, a live acoustic rendition, the longest “Saturday Night Live” performance in history and, most recently, the “Sad Girl Autumn Version,” of which Swift has said, “One of the saddest songs I’ve ever written just got sadder” — “All Too Well” is a kiss-off for the ages.

RELATED: Taylor Swift’s ‘witchy’ new album fuels speculation about her interest in the craft

As Lindsay Zoladz wrote in The New York Times, it is “gloriously unruly and viciously seething,” even as it captures “a young woman’s attempt to find retroactive equilibrium in a relationship that was based on a power imbalance that she was not at first able to perceive.” For Swift fans who’ve been as invested in her personal life as in her music since her debut 15 years ago, the song is no doubt a tremendously satisfying act of score-settling.

Yet, it’s worth considering if something beyond our cultural obsession with celebrity hookups has made it so compelling to so many.

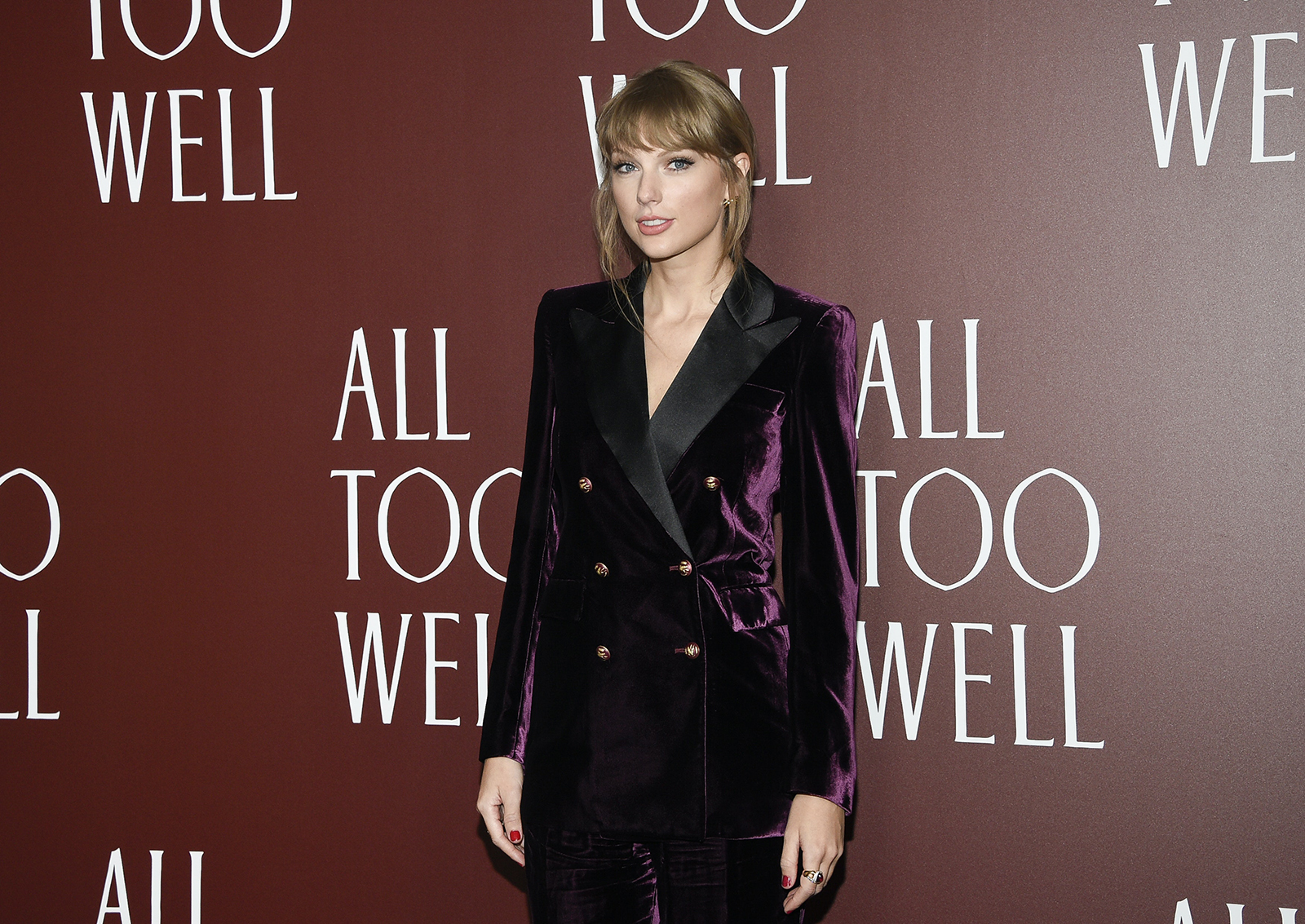

Taylor Swift attends a premiere for the short film “All Too Well” at AMC Lincoln Square 13 on Friday, Nov. 12, 2021, in New York. (Photo by Evan Agostini/Invision)

In its own way, “All Too Well” tells a story not unlike myths of yore. It dabbles not in mythology, per se, but in the so-called “monomyth,” popularized as “The Hero’s Journey” by the folklorist Joseph Campbell almost 75 years ago.

Campbell’s 1949 book, “The Hero with a Thousand Faces,” argued that there was a single story of travel and travail found across cultures, a template for overcoming physical and spiritual adversity.

This journey often involves a trek through the underworld, but its destination could be anywhere: Prometheus ascending to the heavens to steal fire from the gods; Jason and the Argonauts sailing into a sea of marvels; Moses climbing Mount Sinai; or Siddhartha Gautama setting forth from his father’s palace to seek enlightenment.

In all these stories, Campbell identified the monomyth’s “separation-initiation-return” formula: “A hero ventures forth from the world of common day into a region of supernatural wonder,” Campbell wrote. “Fabulous forces are there encountered and a decisive victory is won: the hero comes back from this mysterious adventure with the power to bestow boons on his fellow man.”

Swift’s “All Too Well” follows this trajectory as if written as an assignment for a comparative mythology class. It suggests that failed relationships, too, have their own structure of separation, initiation and return: Two individuals remove themselves from the broader world through a singular connection, become fully ensconced within it and then leave it behind. The journey into a love affair and out again can be its own harrowing hell.

Swift’s lyrics recount a woman venturing into a world of supernatural wonder (“singing in the car, getting lost upstate/Autumn leaves falling down like pieces into place”) and encountering fabulous forces (“Cause there we are again in the middle of the night / We’re dancing ’round the kitchen in the refrigerator light”). Trials ensue through each of the song’s verses until a victory is finally won.

In this Oct. 12, 2013, file photo, Taylor Swift appears at the Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum in Nashville, Tennessee. (AP Photo/Mark Humphrey)

When finally she comes back from her adventure, she is a wounded hero (“From when your Brooklyn broke my skin and bones / I’m a soldier who’s returning half her weight”) and her story of survival — the song itself — is the boon she bestows to all.

Critics of Campbell’s monomyth have pointed out that he often cherry-picked from the world’s traditions with little regard for context, willfully ignoring the complexity and variation of myth in order to privilege a hero’s journey that involved male adventurers and explorers at the expense of other kinds of stories. Swift, by casting herself as the hero of her there-and-back-again tale, also recasts the kinds of trials this ancient quest might involve and what it means to endure and be changed by the ordeal.

Critics of “Red (Taylor’s Version),” meanwhile, have dismissed “All Too Well” as a very public rehashing of a private affair that took place many years ago. Surely, they insist, it must be time to let it all go.

Yet, what are the stories from our past but the personal myths by which we live, told and retold as we search them for meaning?

It is facile to say the faces that fill People magazine are today’s pantheon, the gods and titans our impoverished spiritual appetites deserve. But myths are nothing more than stories that resonate across a culture. They belong to everyone because they reveal to us things we somehow already knew. They are tales we remember because they make sense of things, and they are not so different from other kinds of stories we cannot help but tell again and again.

As with our personal dramas, retelling myths is precisely the point. Whether they recount epic journeys or intimate losses, we often don’t know what they mean until they have been shared — with friends, with therapists or even with millions of fans.

(Peter Manseau is the curator of American religion at the Smithsonian and the author of 10 books, including the forthcoming novel “The Maiden of All Our Desires.” He is on Twitter @plmanseau. The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily reflect those of Religion News Service.)