(RNS) — When I was growing up, I loved to read. I still do. But when I was around 10 years old, I started reading Dungeons & Dragons books. My favorite series was called “Dragonlance,” with more than 30 books, all at least 300 pages long.

I read nonstop.

I loved diving into the fantasy world of elves, wizards, dragons and epic wars. It is because I was a reader at a very young age that I became a writer as an adult.

But reading gave me more than my livelihood. I was very shy during elementary and middle school, and didn’t have many friends. Oftentimes books would be my only company and comfort in my loneliness.

This power of books — to create new realities for readers — is why there’s something particularly heinous about banning books. For many of us, books are not mere assemblages of pages and words; they are worlds into which we have flown, escaped, found solace.

RELATED: Why Black artists are essential freedom fighters

Books contain knowledge that humanizes and horrifies us. A good one can change us, long after we can no longer remember the twists and turns of the plot. Many of them become our friends, our conversation partners, our company when we feel isolated and misunderstood.

Right now, regressive forces in our land are coming up with lists of books that should be banned from schools. In one of the most publicized instances, Republican Texas state Rep. Matt Krause disseminated a list of 850 books that apparently troubled him and asked school districts to report whether any of them are on school library shelves.

In last fall’s Virginia governor’s race, the eventual winner, Glenn Youngkin, ran an ad in which a parent supports banning Toni Morrison’s novel “Beloved” from schools. The book speaks in explicit terms about race and sex, but Morrison, a Nobel Prize-winning author, is a legend of literature. On a scale of absurdity, banning students from reading her is surely near the extreme.

I suspect that the real purpose of these lists is to vault a particular politician or individual into the news. Whether they spark reactions in support of or opposition to their view doesn’t matter; in these political games, all news is good news.

The common thread among the books on these lists, aside from the clawing for attention, is they all contain books that talk or teach about race.

How absurd the notion that people in the United States should learn less about race and not more. As if the problem is that we know too much about the subject and not too little.

We should invite more books about race, racism and white supremacy. We should celebrate our educators who can effectively explain the confounding reality of race — its development, its perniciousness and its ongoing effects — to their students.

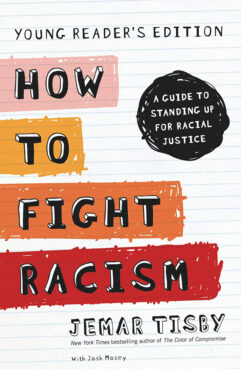

“How to Fight Racism: A Guide to Standing Up for Racial Justice” by Jemar Tisby. Courtesy image

Instead, legislators and talking heads demand that we hide from our minds the painful reality of this nation’s love affair with racial prejudice and pretend that all that is in the past. Then they seek to replicate their ignorance among our schoolchildren.

What’s most eerie about the vogue for banning books is realizing that, if the trend continues, my own books could one day meet this fate. My “How to Fight Racism, Young Reader’s Edition,” may land on one of these banned book lists.

Geared toward children 8 to 12 years old, the book talks about concepts such as racism, white supremacy, race-based chattel slavery, segregation and Black Lives Matter. Almost a quarter of the book is devoted to unpacking the history of racism in the United States in order to help kids understand how we got where we are and ignite in them the desire to do something about it.

Chapter titles include “Confronting Racism Where It Lives,” “How to Explore Your Racial Identity” and “Fighting Systemic Racism.”

I encourage kids in the book to embrace their personal agency and their ability to effect change. I tell them that racial justice is an imperative for a well-functioning society and that even, perhaps especially, as young people they should be involved in the fight against racism.

I tell them: “This fight isn’t just for grown-ups. Some of the greatest advances in the fight against racism have happened because kids fight too.”

My hope is that “How to Fight Racism, Young Reader’s Edition” inspires a new generation of young people to anti-racist action starting right now.

The forces of regression panic when the most disempowered in our society learn to embrace their power. Some will do everything they can to suppress the impulse toward independence. They imprison activists, they burn churches, they make it harder to vote. They ban books.

RELATED: Toni Morrison and the holiness of the living, breathing flesh

The way to battle the ban is to lean in to love. Lean in to that timeless, irrepressible love of books. Lean in to the feeling of being transported by an engrossing story. Lean in to the satisfaction of feeding our famished brains with new knowledge. Lean in to our notorious affair with the written word.

If one day my book lands on one of those lists of banned books, I’m not worried. You can’t ban people from appreciating words, skillfully assembled, soulfully combined. Even if they write lists of banned books as long as a library’s shelves, it won’t douse the fire, and the will, we have to read words.

Bibliophiles of the world, unite!

(Jemar Tisby, the author of “How to Fight Racism, Young Reader’s Edition,” and “The Color of Compromise,” is a historian and speaker on race, religion and politics. He is co-host of the “Pass the Mic” podcast. The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily reflect those of Religion News Service.)