(RNS) — This weekend, I finally got around to reading the Book of Esther.

“Aren’t you a little bit late on that? Wasn’t Purim on Wednesday evening and Thursday?

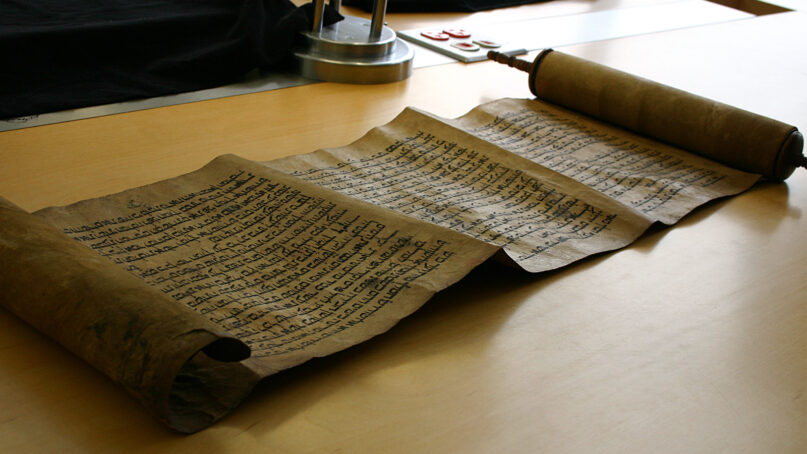

Yes, it was. And yes, we read Megillat Esther (the scroll of Esther, which contains the story of Purim) in synagogue.

But, I did not actually read it thoroughly, and study it, until this past weekend.

That was when I made a startling, yet redemptive, discovery.

Most people never get to the end of the Book of Esther. Yes, Haman gets hanged on the gallows that he had intended for Mordecai. Yes, Haman’s 10 sons are also hanged. And, yes, King Ahasuerus, unable to reverse his original decree that permitted Haman to destroy the Jews, issues a second decree allowing the Jews to fight back against their enemies. Nasty stuff.

But then we get to the very end of the book. Mordecai has ascended to a position of power and influence in the administration of Shushan.

“For Mordecai the Jew ranked next to King Ahasuerus and was highly regarded by the Jews and popular with the multitude of his brethren (rov echav). He sought the good of his people and interceded for the welfare of all his kindred.” (Esther 10:3)

That word rov, which seems to mean “multitude,” is a tricky word.

For it can also mean “the majority.” As in: Mordecai was popular with the majority of his brethren.

Wait. “The majority?” You mean — not all? We’re talking Mordecai here. Didn’t he and Esther just save their people?

The classic medieval commentator Rashi, quoting a passage in the Talmud (Megillah 16b), says that not everyone loved Mordecai — and that, in fact, people complained about him!

“Because many thought that he occupied himself too much with community needs and therefore neglected Torah study, and that he should have remained active on the Sanhedrin.”

The Talmud imagines there were Jews in Shushan who griped that Mordecai was too involved in the greater community.

The Talmud imagines there were Jews in Shushan who griped that Mordecai was too involved in the greater community.

Better that he should have sequestered himself and occupied himself with purely spiritual needs — studying Torah. Better that he should have occupied himself with the particular needs of the Jewish community — remaining active on the Sanhedrin, the Jewish court (which is anachronistic).

What can this commentary teach us about contemporary religious leadership?

Clergy members know they cannot make everyone happy. We speak our moral, theological, spiritual and political truths. That is the prophetic legacy. The biblical prophets were not popular. As the Christian author Frederick Buechner once wrote: “There is no evidence of a prophet ever being invited back a second time for dinner.”

No wonder many rabbis like to quote Israel Salanter: “A rabbi about whom there is no controversy is not much of a rabbi.”

But there is more.

Mordecai’s constituents all had their own ideas about where he should put his time and energy. There is simply no way he could have satisfied everyone — including himself.

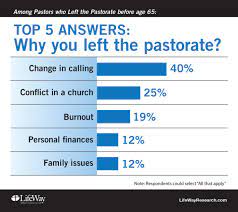

Barna Group, a faith focused research firm, found that 38% of pastors had considered quitting full-time ministry in 2021. Clergy had alarmingly high rates of PTSD symptoms — higher than post-deployment military personnel.

Steven Sandage, the Boston University School of Theology’s Albert and Jessie Danielsen Professor of Psychology of Religion and Theology, writes of today’s clergy:

Depending on the congregation, they might also be expected to be experts in finance, counseling, inspirational leadership, and event planning … Sometimes there are very few boundaries — there can be expectations of being on call around the clock. We’ve also seen in our research difficult relational boundaries where, for example, board members, if they’re frustrated or angry at the leader, can sometimes be intrusive in ways that are really difficult — experiences of relational aggression have been prominent in our research with religious leaders. Then the final one is just that the levels of support and remuneration are sometimes small. When you take all of those factors together, it’s quite a complicated landscape for many religious leaders.

Add to that: Ever since March 2020, when COVID-19 hit, many clergy members had to learn how to be, essentially, television producers. They have learned to be proficient in Zoom, often with inadequate budgeting or staff support.

I read the ancient commentary on Mordecai’s popularity and this is what I take from it.

Yes, you have to proclaim your own truth — your religious truth, as refracted through layers of interpretation and history.

But, also, you have to have your own inner agenda, as refracted through your own strengths and challenges, as well as the often dizzying changing needs of your congregation.

Many different factors go into how we determine our priorities: our talents, strengths, ideology — all of those interacting with the rapidly changing nature of communal needs. By definition, if you do one thing, then you are automatically limiting the time you can spend on something else.

It is a cliche that you cannot be all things to all people. But, at the very least, you can center yourself on your goals, your ideals and your passions.

The ancient sages noticed a certain custom regarding the reading of the megillah, the scroll of Esther, on Purim.

When you read from the Torah scroll, you open the scroll one column at a time.

But, when it comes to the megillah, the scroll of Esther, you must open it in its entirety on the reading table.

Why?

Because the sages taught that the scroll of Esther is not just a scroll. It is an iggeret. It is a letter, an epistle, a formal open letter, to a particular community, addressing their particular needs. As in: the Pauline epistles in the New Testament. As in: the epistles that Maimonides sent to beleaguered Jewish communities, such as Yemen.

The story of Esther is a letter — an epistle — addressed to every generation of Jews. It is about the dangers of powerlessness, and the promise of direct human initiative and intervention.

That piece about Mordecai being popular only with most of his people?

That, too, is an epistle.

To every generation of religious leaders.