LOS ANGELES (RNS) — They were a small, mostly overlooked population of first- and second-generation American immigrants until the United States was attacked, seemingly out of nowhere, by people from the country many of them had left behind.

Suddenly they and anyone who looked like they did were viewed as a threat to national security. Their religion was called into question. And finally, in 1942, about 120,000 people of Japanese ancestry from California, Oregon, Washington and Arizona were sent to “internment” camps for the duration of World War II.

The experience of Japanese Americans after the bombing of Pearl Harbor in 1941 and the United States’ entry into World War II recalls the aftermath of 2001, when anti-Muslim sentiment followed the World Trade Center attacks.

“Buddhist priests were treated the way Muslim imams were after 9/11 and Buddhist temples were treated like mosques. They were seen as places to incite violence and extremism,” said Emily Anderson, project curator at the Japanese American National Museum in Los Angeles, where a new exhibition, “Sutra and Bible,” traces the part religion played in the lives of U.S. Japanese immigrants and their U.S. born children, their incarceration and in their lives that followed.

“It wasn’t just race, but it was a conflation of race and religion that made these people seem un-American, or perhaps even anti-American,” said Duncan Ryūken Williams, director of the USC Shinso Ito Center for Japanese Religions and Culture.

Williams, a Soto Zen Buddhist priest who co-curated “Sutra and Bible” with Anderson, said religion is key to understanding what led to the incarceration of Japanese Americans, as well as how they survived it.

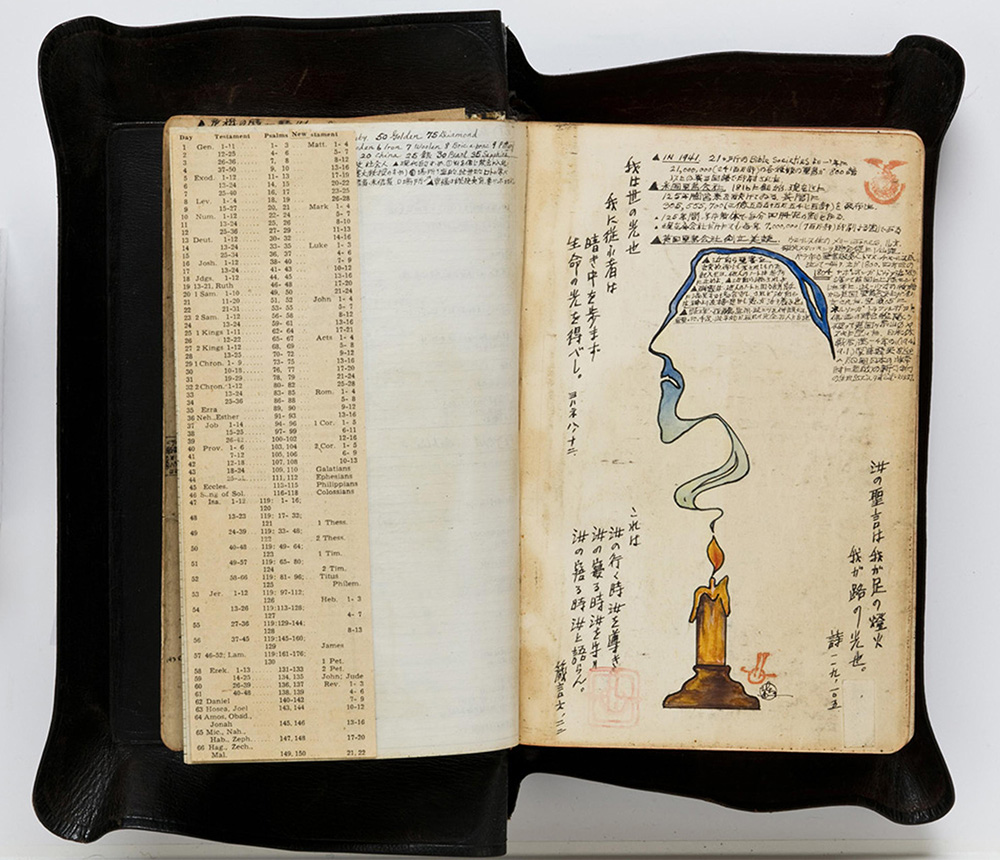

End pages of the first Kitaji Bible, completed by Captain Masuo Kitaji at Poston concentration camp, 1944, on display at the Japanese American National Museum’s “Sutra and Bible” exhibition. Courtesy of Kitaji Family/Hoover Institution Library & Archives

Even before the war began in the Pacific, Buddhist temples had been under surveillance by American authorities. According to Williams, Buddhist priests were among the first people arrested by the FBI soon after the bombing of Pearl Harbor. When the Japanese American community needed their faith leaders most, they were suddenly gone.

“That thing that made them problematic in the eyes of the government was the very thing that they drew on to sustain themselves in this moment of dislocation, in a moment of loss,” said Williams.

When they were forced into the camps, the comfort of their faith was often taken away again. Camp administrators, the exhibit shows, “often favored Christianity, barely tolerated Buddhism, and banned Shinto rituals and worship entirely.”

About a quarter claimed affiliation with various Christian denominations, but even they “were not immune from the indignities of camp life,” the exhibition’s curators note. One Bible is stamped with the word ‘EXAMINED,’ certifying that it had been inspected for subversive material.

Homilies collected by sympathetic non-Japanese Christians and published by the American Friends Service Committee under the title “The Sunday Before” capture Christian pastors’ words written before the impending incarcerations. In one sermon, the Rev. Lester Suzuki mourned with congregants at the Los Angeles Japanese Methodist Church: “You paid for the pews, the altar, and you contributed to the building of it. But now you must vacate it, not knowing whether you will be able to use it again.”

Also on display are the Kitaji Bibles, named after Salvation Army Capt. Masuo Kitaji, who, during the camps, annotated the Bible in English and Japanese. For Kitaji, according to the exhibition, translating and commenting on the Bible was a way to deliver the gospel to new converts, as well as a “means of enhancing the glory of God.”

Heart Mountain sutra stones on display at the Japanese American National Museum’s “Sutra and Bible” exhibition. Japanese American National Museum, Gift of Leslie and Nora Bovee, 94.158.1.

The exhibition also includes stones inscribed with Buddhist Scripture that were unearthed from the Heart Mountain concentration camp cemetery in Wyoming. Known as the Sutra Stones, scholars have linked the text to the Lotus Sutra and theorize that Nichiren Buddhist priest Nichikan Murakita, a master calligrapher, may have been responsible for writing and burying the stones while incarcerated.

RELATED: ‘We’ve been here all along’: Author pushes back against erasure of young Asian American Buddhists

Most poignantly, “Sutra and Bible” captures how religion provided a sense of belonging among Japanese immigrants, many of whom had arrived in Hawaii and the continental U.S. in the late 19th century. The museum has gathered images of congregations posing for photos in front of their temples and churches.

That belonging translated to sacrifice for their country. Japanese Americans were permitted to volunteer for the U.S. Army and served in a segregated unit commanded by white officers.

Their religion accompanied Japanese American soldiers to the battlefield. Displayed are Buddhist prayer beads a soldier received from his mother and a dog tag handmade by a Buddhist soldier, who, in it, etched the words, “I AM A BUDDHIST”; at the time, dog tags recognized a soldier’s faith, but the only options were “P” for Protestant, “C” for Catholic, “H” for Hebrew or Jewish and “blank” for no affiliation.

Memorial tablets honoring soldiers from Hawai’i who were killed in action during World War II, on display at the Japanese American National Museum’s “Bible and Sutra” exhibition. On loan from Liliha Shingon Mission, IL.1.2021

Some religious organizations and individuals stood up for Japanese Americans before, during and after incarceration. Pamphlets advocating for Japanese Americans appear in the museum’s display, including a Quaker brochure advertising housing for Japanese Americans at church and temple hostels after incarceration.

But Buddhists and Christians alike, Anderson said, faced contradictions. Buddhists experienced persecution for their faith and faced accusations of being un-American “even though they’re supposedly in a country where all faiths should be embraced.”

For the Christians, she said, “there was a sense of betrayal, because they believed in America as both a fair and Christian nation.”

Christians may have received “slightly better treatment,” Anderson added, “but it didn’t change the fact that they were also all incarcerated. It didn’t matter that you worshipped in the same churches and believed the same things. You were Japanese and, therefore, your faith would not protect you.”