(RNS) — The year was 1966, and I was 12 years old.

“Your cousin got two of these albums for her birthday. Do you want one?”

With those words, my aunt handed me the Simon & Garfunkel album, “Parsley, Sage, Rosemary and Thyme.” That album changed my life. Simon & Garfunkel became my favorite popular music artists — yes, surpassing the Beatles, who up to that moment, had been my No. 1.

I wore out the grooves of “Parsley, Sage.” Two years later, when their album “Bookends” came out, I wore out the grooves on that album as well. Simon & Garfunkel’s hymn to our national yearning, “America,” became my favorite pop song.

Several years ago, Time magazine named Paul Simon one of the hundred people who have shaped the world. He certainly shaped my world. Moreover, he epitomizes the plea of the psalmist: “Do not cast us off when we are old.” At an age when many peers in his age cohort would have settled back into retirement, he was still growing creatively, producing new work. and recording new albums.

Image via Pushkin

For that reason, I rejoiced when a colleague sent me a gift of the new audiobook “Miracle and Wonder: Conversations With Paul Simon,” with Malcolm Gladwell and Bruce Headlam. In that audiobook, the authors engage the retired rock star, now 80 years old, in a series of conversations about his music.

Among my top three musical crushes — the Beatles, Bob Dylan and Paul Simon — there was no question that my personal connection to Simon was the deepest.

A memory: My late father fulminating about the song from “The Graduate,” “Mrs. Robinson.”

“That line about ‘Jesus loves you more than you will know’ — what are two Jewish boys from Queens doing singing something like that?”

My father was on to something, and it was paradoxically what drew me to Paul Simon. We had the same roots — Queens. I spent my toddler years in Jamaica; Simon had grown up, a few miles away, in Kew Gardens Hills.

The musician Donald Fagen of Steely Dan has described Simon’s childhood as:

a certain kind of New York Jew, almost a stereotype, really, to whom music and baseball are very important. I think it has to do with the parents. The parents are either immigrants or first-generation Americans who felt like outsiders, and assimilation was the key thought—they gravitated to black music and baseball looking for an alternative culture.

The Simons belonged to a synagogue, but were not especially religious. Paul’s mother, Belle, had come from a religious background and she would go to the synagogue herself on the High Holy Days. Simon once told an NPR reporter, “I was raised to a degree, enough to be, you know, bar mitzvahed and have that much Jewish education, although I had no interest. None.”

In other words, Paul Simon is like many other Jews who grew up in the 1950s.

Gladwell (who is not at all Jewish) asks Paul Simon point-blank: “Where do you locate your Jewish heritage in your songwriting?”

It’s hard to say, because it’s a cultural sensibility that you grow up with. How, exactly, you define that — I don’t know. It’s there, but it’s only there because that’s the world I grew up in. It’s not a world that I wanted to grow up in. It’s not a religion that I chose to follow. But, it was a culture that I was comfortable in and aspects of it was something that I admired.

(By contrast, Art Garfunkel’s Jewish roots run deeper. He sang in his synagogue choir and adeptly sang the liturgy at his bar mitzvah service.)

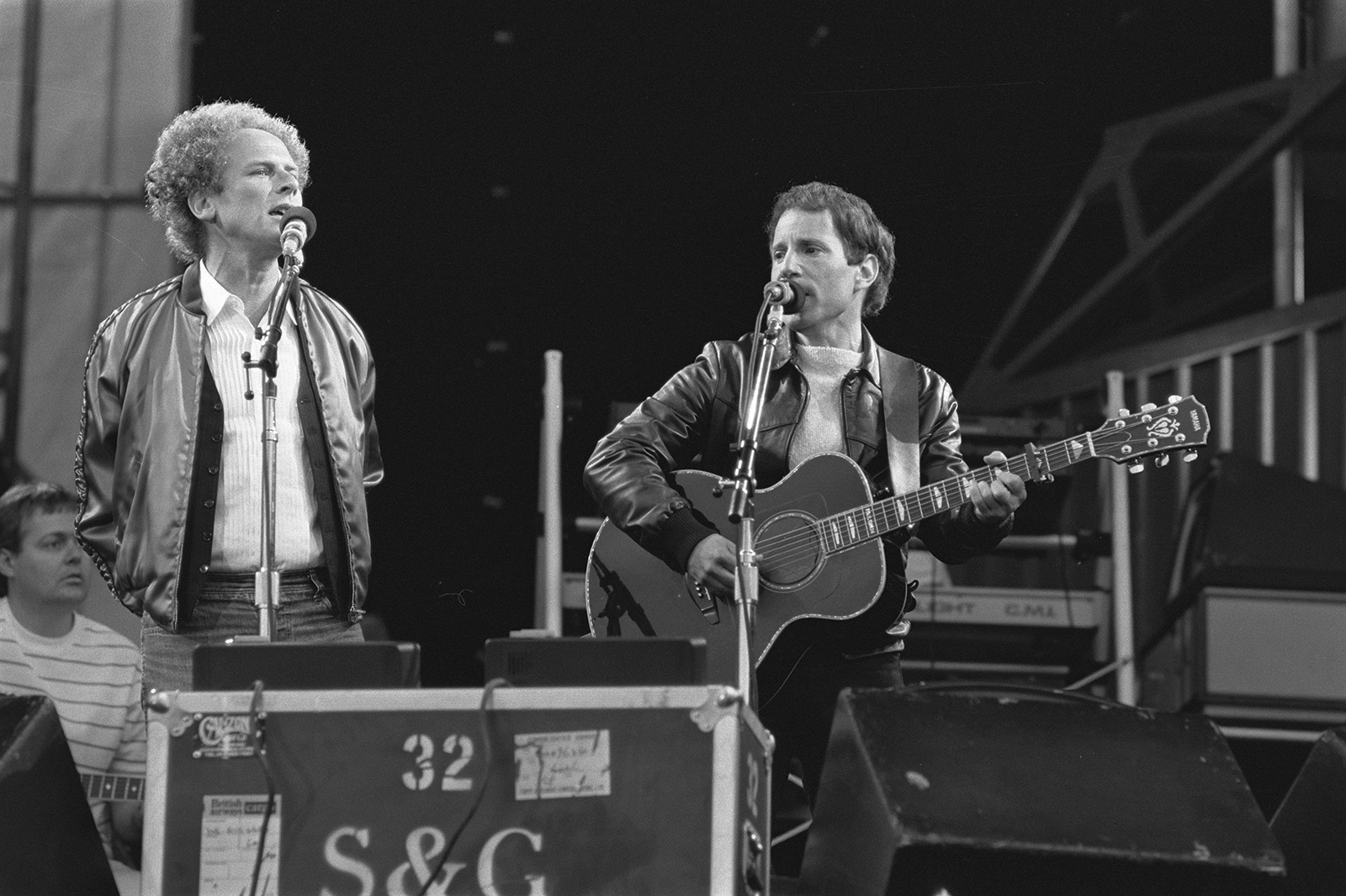

Art Garfunkel, left, and Paul Simon, the duo of Simon & Garfunkel, perform in the Netherlands in 1982. Photo by Rob Bogaerts/Anefo/Wikipedia/Creative Commons

Paul Simon had no peers, among popular artists, in his adeptness in importing musical styles from all over the world. Gospel, reggae, zydeco, jazz, African music — all found a home in his music. He was undeterred in his musical eclecticism and in his constant experimentation and seeking of perfection in his craft, even as his compositions became richer and more complex.

But, of all the world music that Paul Simon brings into the studio, there are several musical themes you will not hear: klezmer, or Middle Eastern Jewish music.

Is it really possible there are no Jewish musical influences in Paul Simon’s work?

Gladwell found that hard to believe. He keeps pushing. He mentions the song “Take Me to the Mardi Gras,” from Simon’s second solo album, “There Goes Rhymin’ Simon.”

He asks Paul: “What about that line in the song — ‘Tumba tumba tumba Mardi Gras’?” Gladwell recalls the Yiddish folk song “Tumbalalaika.” He asks Paul if that was the origin, even unconsciously, of that seemingly disposable nonsense word in “Take Me to the Mardi Gras,” which already combined numerous musical styles.

Paul Simon rejects that piece of musical archaeology. He says the word “tumba” actually comes from an old New Orleans song.

Gladwell thinks Simon “doth protest too much,” that he was perhaps borrowing “tumba,” even unconsciously, from the Yiddish song.

In other words, a Judaism — a Jewish culture — so deep as to be subterranean.

Here is the thing, though. While Simon lacks Jewish ethnic influences in his music, many of his lyrics have Jewish shadows — perhaps even ghosts.

Simon & Garfunkel album cover for “Bookends.” Courtesy image

Here is the Paul Simon siddur, if you will.

Start with the album”Bookends.”

There is that piece, “Voices of Old People.” It was a recording Art Garfunkel made, in Jewish nursing homes, of old people reminiscing about their lives.

Then, on to “Fakin’ It,” which includes within its lyrics a parable about the American Jewish immigrant past, and the inability to escape it.

Prior to this lifetime

I surely was a tailor

(Good morning, Mr. Leitch.

Have you had a busy day?)

I own the tailor’s face and hands

I am the tailor’s face and hands and

I know I’m fakin’ it

It turns out Paul Simon’s grandfather, also named Paul Simon, had immigrated to the United States from Galicia.

He was a tailor.

Paul Simon, the songwriter, was telling the truth: We are always our grandparents’ face and hands.

”Still Crazy After All These Years” album by Paul Simon. Courtesy image

Go to his 1975 album,”Still Crazy After All These Years.”

“Silent Eyes” could well be Simon’s most Jewish song. He longs and weeps for Jerusalem, in prayerlike phrases — “She is sorrow, sorrow / She burns like a flame / And she calls my name.” It envisions a time when all will be called to account — “We shall all be called as witnesses / Each and every one / To stand before the eyes of God / And speak what was done.”

Go to his 1983 album “Hearts and Bones” — to the title track — “Hearts and Bones.” “One and one-half wandering Jews, free to wander wherever they choose.” Paul is, himself, the “one” Jew, with his ex-wife, the late Carrie Fisher, being the “one half wandering Jew” — and in their lives and careers, in fact, they did wander wherever they chose.

Go to his 2011 album, “So Beautiful or So What” — to the song “Rewrite.” It is a song about a man’s regrets, and how he wants to rewrite his biography — to make it more heroic, and more meaningful. The man in the song wants to rewrite his book of life, his sefer chayim. In the song’s chorus, he turns to God and, almost in the voice of the ancient psalmist, the man says: I had no idea that You were there.

Does Paul Simon know God is, in fact, there?

Gladwell’s book is a masterpiece. If you are a Paul Simon fan, or a fan of popular music in general, it will offer you an unparalleled insight into the mind of one of the great creative geniuses of our time.

Who, like many of us, is far more Jewish than he had ever thought.