(RNS) — How does a force of nature stop? This is the question I find myself wrestling with after the news of the Catholic feminist theologian Rosemary Radford Ruether’s passing on Saturday (May 21).

Ruether has been a profound influence on my life since I was 18 or 19, sitting in the office of the Committee in Solidarity with the People of El Salvador and reading her early book, “Liberation Theology: Human Hope Confronts Christian History and American Power.” I remember, as I read, feeling an electrifying relief as a number of my intellectual, political and spiritual questions resolved. The setting is important; Ruether’s theology is rooted in activism and she gave me the bridge between the religious and activist sides of my life.

I later had the honor of studying with her while at Garrett-Evangelical Theological Seminary, and she was a member of my doctoral committee at Claremont Graduate University. Ruether’s constant vitality was not only apparent in her prolific output — for stretches of her life she would publish a book or two a year — but in an élan that simply radiated from her personality and made her classes fly by. Her unflagging sense of humor often graced her writings and was apparent in the chuckle that regularly adorned her speech. Everything about her pointed toward the integration of critical thought and lived experience.

Ruether was one of the most important theologians, not just of the 20th century, but of the entire Christian tradition. Her 47 books cover topics ranging from the early church to examinations of Christian antisemitism, the Israel-Palestine conflict, the nature of U.S. history, the environmental crisis, the mental health profession and, of course, the uncovering of women’s contributions to religion and her pioneering work in feminist theology. In her books, she wrote with a prose so clear it often masked just how deep the complexity of her thought went.

Ruether entered college to study visual arts, and when I asked her how her training in visual arts had an impact on her theology, she replied that painting trained her to “see things as a whole.” Her method would often start with the diagnosis of a present injustice. From there, she would paint a picture that held the sweep of “Western” history from ancient Sumer to the present together in a coherent story.

She came to history with a profound sense that we have a responsibility to repair the legacies of its horrors, so her histories generally reflected a critical look at the strands she was in a position to do something about and left room for others to add their stories and perspectives to the larger picture. If her histories recapitulate the construct of “the West,” they do so in a way that is chastened by her early experiences in the civil rights movement and subsequent activism, as well as a profound dialogue with voices from every part of the globe.

Her arguments would often clinch around the phrase “we need”: What she wanted theology to do was to sustain communities and provide tools for moving toward a world in which the promises of equality and justice for everyone are realized. She summed up her own approach as a dialectical methodology that “seeks to be both radical and catholic in such a way that the radical side is not just an ‘attack,’ but the critical word of the tradition itself to judge, transform and renew it in new and more humanizing ways for all of us.”

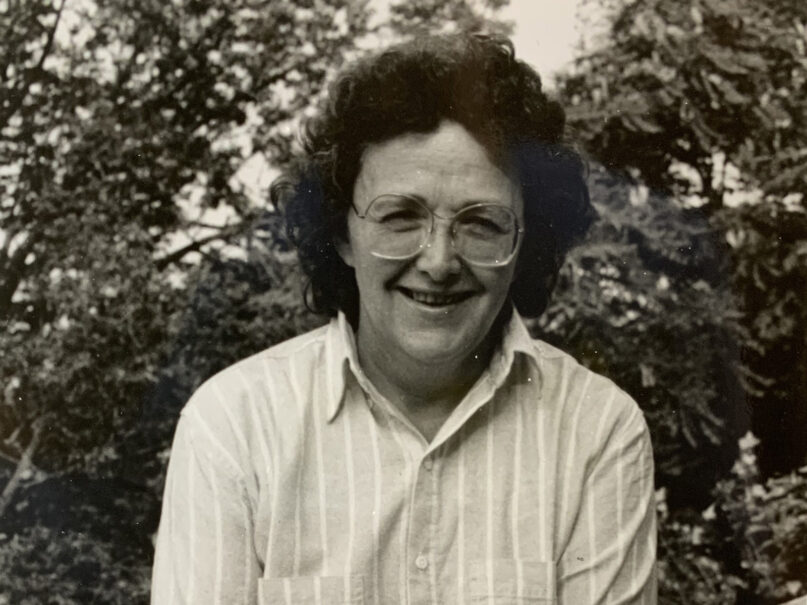

Rosemary Radford Ruether speaks about writing one of her books in 2010. Video screen grab via Fortress Press

Ruether derived this dialectical methodology in large part from the biblical prophets, drawing the lesson that critique must be above all a communal self-critique. She had a deep ability to hold together a commitment to stay with communities, even as she constantly searched for the most acute critical vantage point she could find.

Her concept of “Women-Church” outlined how she understood her work as a Roman Catholic feminist to be a dialectic between a commitment to the reform of a larger community and the creation of counterspaces that allow for independent voices to name experiences on terms not set by the dominant community.

A story shared by a faculty member at an event at Garrett-Evangelical Theological Seminary illustrates what I call the “critical fidelity” that Ruether’s life and work modeled. During a faculty boating trip on Lake Michigan, the wind came to a dead halt, leaving the sailboat motionless. While everyone waited for the wind to pick up, Rosemary rowed a little boat in circles around the sailboat. The laughter that greeted this story expressed the recognition of just how apt a metaphor it was — Ruether both refused to abandon flawed religious communities and to play on their terms.

Ruether’s passing is a keen reminder of a primary lesson from her theology: There is no once-and-for-all achievement of justice, but each generation has to figure out for itself how to rebalance relations that fall into distorted and unjust patterns.

She modeled a pursuit of justice that was both more rigorous and less moralistic than many efforts I see today.

I will admit feeling a bit lost and disoriented without a sense that she is “there” to turn to for guidance in our current crises of gun violence, wars of aggression, threats to sexual freedoms and the constant hum of looming environmental collapse. But, of course, she is still “here” in her publications, the legacies her students carry on and, above all, in the changes unleashed by the social movements she was a part of.

Ruether was one of the feminist voices who diagnosed the hope for personal immortality as a form of male egoism. Like the Psalmist, who declares that God is among the living not the dead, she provided reminders that our spirituality must renounce the question “what is going to happen to me” and focus on our life together.

To this end, I invite you to remember Ruether by finding, committing to and humanizing the struggle for justice wherever you can.

(Dirk von der Horst is instructor of religious studies at Mount St. Mary’s University, Los Angeles. He is the co-editor of “Voices of Feminist Liberation: Writings in Celebration of Rosemary Radford Ruether.” The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily reflect those of Religion News Service.)