(RNS) — Religion is saturated with “what” and “why” questions. What do you believe? Why do you believe it? But often “how” — How did we come to adopt this religious identity? How do we sort out its contradictions? — can be more difficult to ask, and to answer.

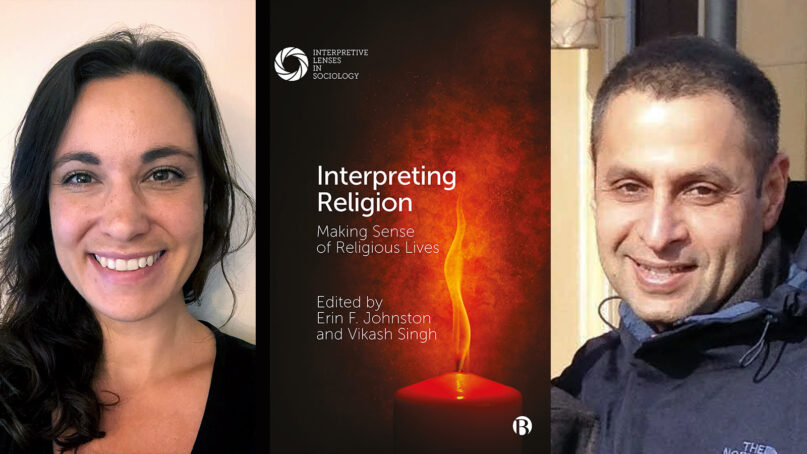

In a new book, “Interpreting Religion: Making Sense of Religious Lives,” editors Erin F. Johnston and Vikash Singh go beyond the what and why of religion to ask how religious people make meaning, and how those meanings are transmitted, contested and remade. The volume is broad in scope, brimming with textured explorations of how religious and spiritual people make sense of themselves and their world.

The book covers topics ranging from how queer Christians rewrite narratives in which they are cast as sinners, to how the descendants of Holocaust survivors innovate religious rituals in the midst of generational trauma. The net is cast both deep and wide, inviting readers to reckon with their own hows — the process of forging meaning for themselves.

In two separate interviews, Religion News Service spoke with Johnston, a senior research associate at Duke University in North Carolina, and her co-editor, Singh, associate professor of sociology at Montclair State University in New Jersey. They discussed religion’s double-edged nature and the world’s evolving religious landscape. Their interviews were combined and edited for clarity.

The book covers topics ranging from totalitarianism in China to the religious trauma of Holocaust survivors’ descendants. What are some common threads?

Johnston: There’s a central thread of reflexivity — it’s not just about how the people in this religious group are making sense of themselves or the world, it’s also about how I as a scholar, who may or may not be a member of that community, am making sense of those meanings. It’s meta-level reflection.

Erin F. Johnston. Courtesy image

Jodi O’Brien’s chapter is a particularly good example. She’s interested in how queer Christians make sense of themselves and how that has changed over time. As someone who identifies as queer, her own understanding of herself has shifted due to her research. She couldn’t quite make sense of how people who were both Christian and queer tried to inhabit both worlds and the double stigma of being both queer and Christian. Her respondents pushed back and said, “No, that’s not how we understand our experience. We understand our identity as being defined by negotiating that tension, living the contradiction of these two identities.”

That transformed how she thought about these individuals’ experiences and caused her to reflect in new ways on her own coming-out story.

The book shows that religion can be wielded as a tool of oppression or of resistance. How does your book illuminate this tension? What does this contradiction tell us?

Singh: Aseem Hasnain’s chapter on Shia Muslims in modern India looks at Shia identity in reference to Hindu nationalism, a form of identity, and of subjugating and disenfranchising minority groups. George Lundskow’s chapter talks about white male supremacy as religion and how it enables forms of domination, and Yong Wang’s chapter on totalitarianism in China shows how religion-like qualities embedded in nationalism are being used to suppress people’s freedoms.

But Hasnain talks about how Shias mobilized their collective identity to resist domination by the majority ideological force. In a pandemic, when people would otherwise be disaffected with religion, many people are looking for some sort of spirituality for meaning.

Johnston: Religion can be interpreted differently. The religious texts, rituals, traditions can be read differently, and those different meanings do matter. Interpretations translate into very different types of action in the world.

Much ink has been spilled over the rise of the religious ‘nones’ and the spiritual but not religious. Based on your research, are personal, non-institutional forms of spirituality gaining ground?

Singh: People who are otherwise disaffected with religion and religious baggage are choosing their own forms of spiritualism and religion. That’s something we see in Janet Jacob’s chapter on the grandchildren of Holocaust survivors. They have this really conflicted relationship with religion but adopt different meanings, by seeing God as mother or re-interpreting sabbath rituals. You can redefine traditional religion to be more in agreement with modern values, like gender equality, pluralism and multiculturalism.

Vikash Singh. Courtesy image

At the same time, fundamentalism continues to be strong, even in these new generations. Weeks ago, an 18-year-old went to a predominantly Black area (in Buffalo) and committed a mass shooting at a grocery store, driven by white supremacy.

So there’s a turn toward redefining religion in a way that agrees with your own moral choices. But we have to be wary of over-reading that phenomenon, because there is that more conservative and reactionary aspect of religion that continues in the younger generation as well.

Johnston: I see a rising emphasis on more practice-oriented forms of spiritual life. People seem to be seeking something that strikes a balance between a very individualized spirituality and rigid traditions that don’t allow a lot of flexibility. In between those things are people whose religious life is grounded in a personal discipline that has historical roots in a particular religious tradition but also has a degree of personalization that allows you to focus inwardly and outwardly. Communities that have orientations that allow for that combination will be very appealing to people.

What do we lose when we try to isolate religion from the study of culture and society?

Johnston: We miss the way the religious takes root in seemingly secular aspects of everyday life, at hospitals or college campuses. If we try to separate religion, we tend to only study it in explicitly religious institutions. But religion and religious people matter in most contexts.

There can also be a value to using concepts from the study of religion to examine secular ideologies. In the chapters on totalitarianism and white male ethnonationalism, the authors are thinking about secular ideology as religion and asking, ‘what do we gain by thinking about those ideologies through the lens of religion?’

RELATED: The danger of finding our meaning at work

Can you talk about the concept of ‘re-paganism’ and how you’re seeing it in today’s culture?

Singh: Paganism was everywhere in the ancient world before the rise of monotheistic religions. People worshipped deities who were local and much more like ideations of the intimate concerns of their daily lives. They were trying to make sense out of their society and living conditions as a way for them to get some sort of control.

At some level, I would say there is something similar going on now. People are looking at ways to interpret their living conditions, their needs, ideas of gender equality, racial equality, economic justice, deeper meaning. People do that through certain ideas and symbols that are available to them. So what these postmoderns are doing is not very different from what these indigenous and traditional societies used to do back in the day.

The book concludes with the idea that religions of the world have a choice to make. What is that choice, and what are its consequences?

Singh: These religions can continue to be relevant by seeking out the more narrow or reactionary side of human subjects, or they could go for the more multicultural, tolerant approach. This theme is well-covered in O’Brien’s chapter on LGBTQ Christians. It looks at how some of these churches are changing themselves to be more accepting of people, to see LGBTQ people as the most threatened of groups, and thereby, as excellent subjects for Christianity, which appeals to the downtrodden. Then there’s the other side, the more reactive side.

Religions can move both these ways, and they have a choice to make, much like modern subjects themselves.

RELATED: Pagans honor the Earth on May Day. But for many, nature is not enough.