(RNS) — Several years ago, Elder Jeffrey Holland publicly retracted a faith-promoting story he had shared in a training for mission leaders of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. In the weeks after he first presented it, the story went viral on social media and was published in the Church News. Then Elder Holland learned that some elements of the story were not quite true.

So he did the classy thing, calling attention to the fact that the family in question had informed him the story was inaccurate. He asked church members to stop sharing it and preaching about it (which is why I am not recounting its details here), and he publicly thanked the family for bringing the error to his attention.

Then the story faded away, so much so that when I Googled it last week it took a couple of minutes even to find it. Elder Holland’s mea culpa had no lasting negative impact on the church, its reputation or its mission. He made a mistake; he acknowledged it openly; he corrected it. And we all moved on. Yawn.

RELATED: LDS elder — a former college president — may have plagiarized General Conference talk

The reason I was revisiting this incident last week was because of the less helpful way the church initially responded to Religion News Service’s reporting about portions of Elder David Bednar’s recent General Conference talk that appeared to be plagiarized verbatim from a sermon by a deceased Protestant pastor. An RNS reporter brought the questionable passages to the attention of the church’s public affairs department, asking if the church wished to make a statement. The next day, it did:

“Mr. Reid was mentioned by name and referenced on multiple occasions in footnotes. The transcript of his remarks is published for all to see. For those who would try to find fault, we would invite you to consider the spirit of his message.”

I’m noticing several developments here. First, the church appears to be claiming the footnotes and quotation marks — that were not present in the original published talk — had been there all along. (As though no one had thought to take screenshots in 2022?)

Second, the church cast itself as the victim of fault-finders who dared to imagine that an apostle who had served as a university president should not plagiarize the writings of others.

And third, it invited us to consider “the spirit of his message.” This seemed to suggest that presenting someone else’s sermon as your own is fine as long as it was a good sermon.

At least, that is how the statement sounded to me personally. On the other hand, there exists the possibility that the spokesperson simply didn’t know that someone at the church had fixed the problems overnight, so that by the time he looked at the conference talk and crafted the church’s initial statement, everything looked fine, and he could not see why anyone would regard parts of the conference talk as plagiarized.

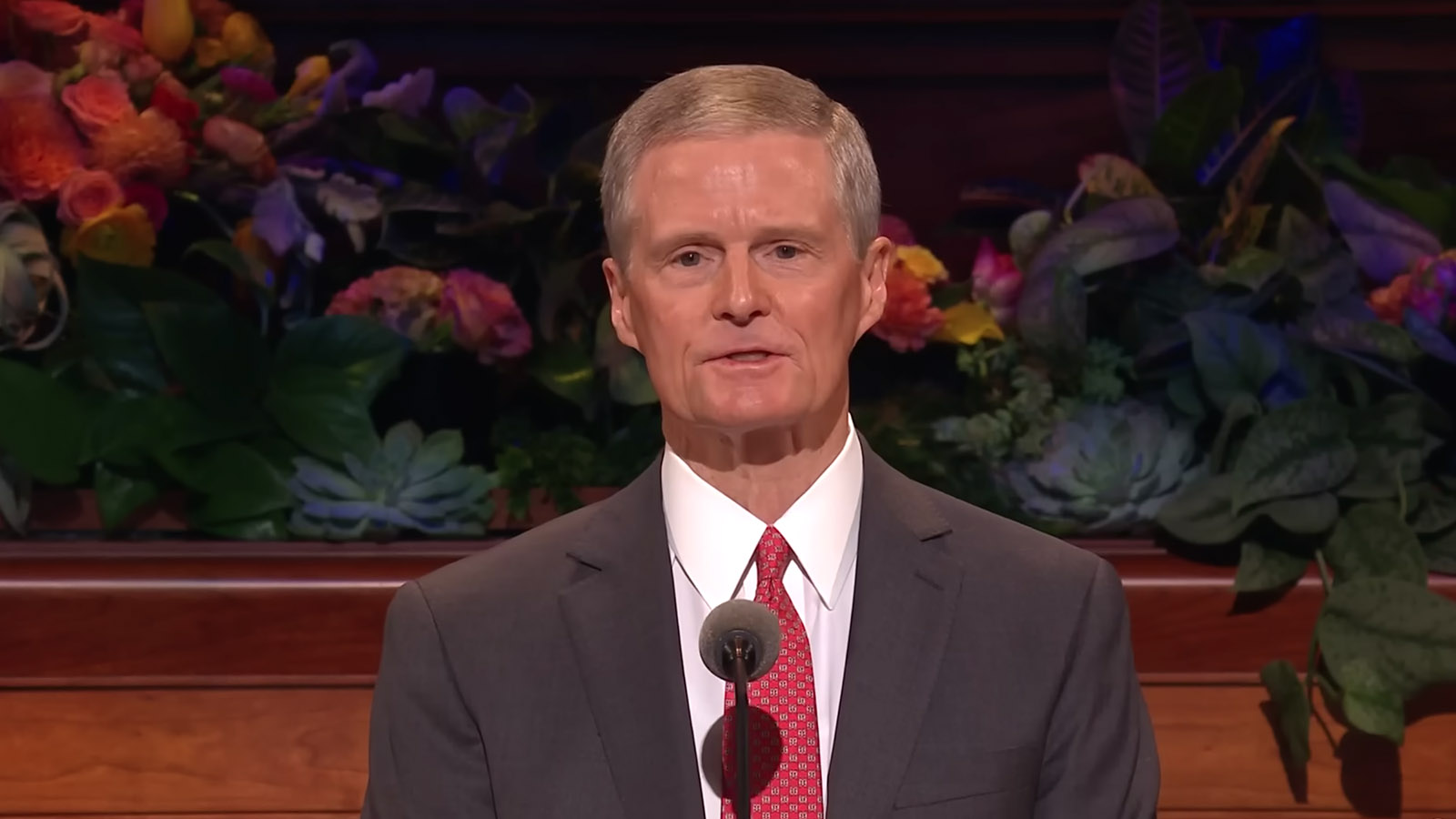

Elder David Bednar speaks at the General Conference of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, held Oct. 1-2, 2022, in Salt Lake City. Video screen grab via Intellectual Reserve Inc.

Let me be clear: I sincerely doubt Elder Bednar ever intended to commit plagiarism. What I imagine happened is he or an assistant had collected his notes on a particular biblical passage over time, and those notes included cut-and-pasted materials from various sources. I’m guessing these included the sermon from John O. Reid as well as his own previous sermons (Bednar also quoted a passage verbatim from his own 2005 conference talk “The Tender Mercies of the Lord”). Only they were not marked as previously published material. And then those sources likely got repurposed in this year’s conference talk and no one thought to run a plagiarism check on the finished product until it was too late.

It happens. Just ask historian Doris Kearns Goodwin. But what makes the church look worse than a small-scale plagiarism scandal that was likely accidental is the first statement’s essential denial that it happened or was in any way problematic.

I was heartened to see that in a follow-up email, the public relations spokesperson admitted to an “editing oversight” and stated that once the errors were recognized, they were quickly corrected. I’m not sure if the second statement occurred because the spokesperson had at last understood that Elder Bednar’s talk had been doctored post-publication, but I’m grateful for the clarifying second statement.

It was not quite an apology, but it was a marked improvement from the church’s initial adversarial defensiveness that simply compounded the initial breach of trust.

It would have been helpful if the church practiced more transparency all down the line: transparency about how general conference talks are written and whether assistants are involved, and also transparency about how the public affairs department gives official responses to media inquiries.

And it would have been even more helpful if Elder Bednar had issued an actual apology.

Apologies are painful to give, but they are vitally important. It’s hard to understand why the church is so allergic to apologies. We are a people who cry repentance, who preach a gospel of choice and accountability. We also preach that repentance will be followed by the fresh mercies of God.

But that’s for individuals, and apparently not for the church as an institution. In 2015 President Dallin Oaks said that “the history of the church is not to seek apologies or to give them” and that “we look forward and not backward.”

I’m interested in knowing why this is our approach, especially when there is so much research lately about the power of apologies in building trust. Writing in the Harvard Business Review, Maurice Schweitzer, Alison Wood Brooks and Adam D. Galinsky note that all companies need to apologize from time to time, and that a well-crafted and sincere apology “can restore balance or even improve relationships,” actually increasing rather than decreasing customers’ trust. One study cited in the article noted that in cases of medical malpractice, doctors were concerned that if they apologized for something they had done wrong, lawsuits would increase. The new approach actually had the opposite effect, resulting in less litigation, not more.

Obviously, the LDS church is not a traditional “company” in a consumer sense, yet it is absolutely an institution built upon relationships. And healthy relationships depend upon humility and being accountable to each other.

I think the inability to apologize is damning to us spiritually, as a church. I mean “damning” in the Latter-day Saint sense of the word, that it impedes our progress. There is so much freedom in being able to say “I messed up and I am so sorry.” President Oaks was right in saying we are a people who look forward, but we can’t do that in a meaningful way unless and until we’ve openly confronted the wrong we’ve done too.

When the church fails to acknowledge even small mistakes — like when it appeared to be trying to pretend Elder Bednar’s plagiarism didn’t happen — it erodes its own credibility with the bigger things, such as how well it says it has handled cases of sexual abuse.

We can do better than this.

Related content:

How Mormons are addressing sex abuse – too little, too late