(RNS) — As many Americans are still processing Thursday’s (Oct. 13) climactic latest hearing of the Select Committee to Investigate the January 6th Attack, others want us to just move on already, claiming the committee is little more than political theater or fearing that subpoenaing — never mind indicting — a former president will render the United States a “banana republic.”

Full accountability for all participants in Jan. 6 is not only a legal and moral necessity, but offers us a chance to break a toxic historical pattern that dates at least back a century and a half. We can only do so by pursuing full accountability for all participants in the Jan. 6 insurrection.

Our history is one of trying to push past divisions at times of great national tension and strife. We have erred in forgiving wrongdoers for the sake of unity at the expense of other key members of our polity. Whenever we choose to ignore what has happened for the sake of “just moving on,” we cause untold harm. And on the national level, when we do this, it generally reinscribes white supremacy.

Shortly after the Civil War ended, white northern clergy began encouraging reconciliation with white southerners, even at the expense of justice and safety for newly emancipated Black Americans. The appeasers went so far as to urge that their fellow northerners ignore news reports of abuse or barbarities against former enslaved people committed by white southerners.

RELATED: The journey from the Jan. 6 insurrection to Martin Luther King Day

One reason for this move, as historian Hanne Blank puts it, is that “forgiveness — and finding common ground — between white southerners and northerners was part of the larger political project of thinking about the U.S. as a union that was ‘unbreakable.’”

In other words: They were focusing on getting back to the business of being one country again.

But, of course, it’s impossible to separate this move from white supremacy, since that reunification was predicated not only on white northerners ignoring white southern violence against Black people, but on the assumption that the “we” who had been fighting were white, the “we” who would make up were white, and that “we” would not ask anything of those so attached to the institution of slavery that they were willing to wage the bloodiest war in American history over it. And perhaps “we,” united in this way, could thus also exclude Black Americans from the equation, making it easier to deny them the full rights of citizenship and belonging.

Throughout postwar Reconstruction, white Protestant leaders put out the message that forgiveness, sacrifice and atonement were the key principles and that their congregants should forgive white southerners unconditionally, without asking for, or waiting for, accountability or repentance.

This was a convenient way to reinscribe white supremacy at a moment when it was in grave jeopardy; support from the white northern establishment for true Reconstruction, which would have demanded repentance, justice and equality, would have put their northern whites’ own superior social status at risk. Calling for forgiveness and unity, without looking too hard at the crimes that required exoneration, instead enabled the white men of the North to move forward without troubling their own status quo.

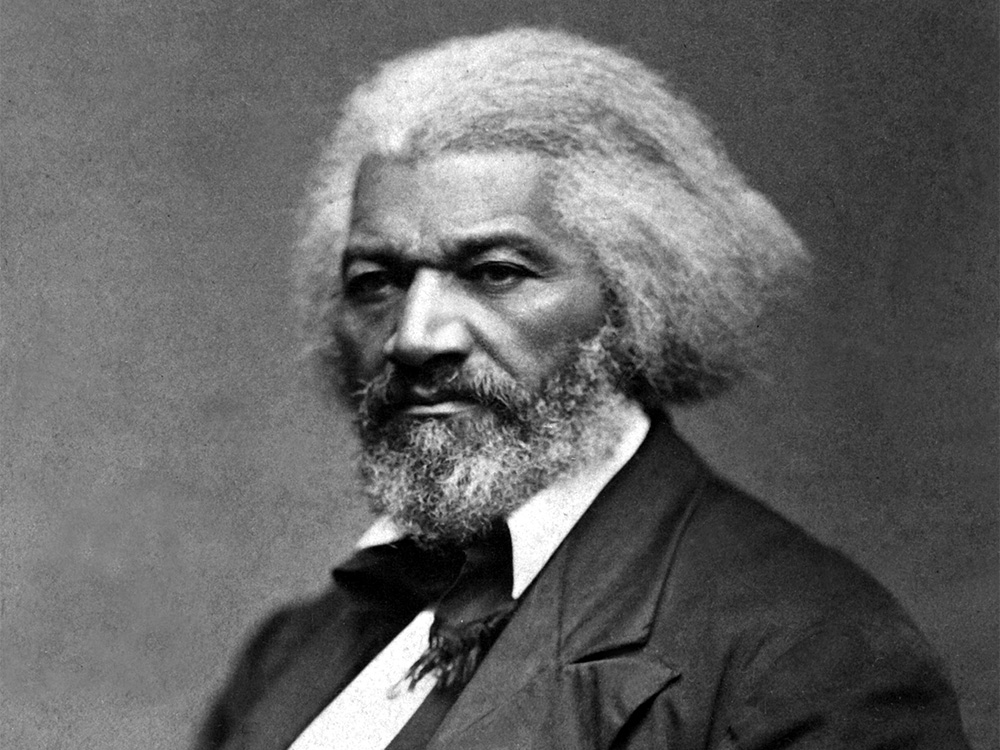

Frederick Douglass, circa 1879. Photo by George K. Warren/National Archives/Creative Commons

Many who advocated for human and civil rights for all Americans at the time — Frederick Douglass and Frances E.W. Harper, among other Black and white thinkers — argued that Christianity demanded repentance from former Confederates as a condition of their forgiveness. In 1871, Douglass gave a Memorial Day speech at Arlington National Cemetery in which he said,

We are sometimes asked in the name of patriotism … to remember with equal admiration …those who fought for slavery, and those who fought for liberty and justice. I am no minister of malice … I would not repel the repentant, but may my … tongue cleave to the roof of my mouth if I forget the difference between the parties to that terrible, protracted and bloody conflict.

Those who had gone to war to defend the institution of slavery could come back into the conversation, were they to work toward repair, Douglass was saying, but the unity of those with privilege could not be made more important than justice for those without.

Yet that’s what happened, and our country has had to live with the legacy of the choice to prioritize unity over accountability and forgiveness over repentance. That choice has caused untold suffering and oppression for generations.

And, indeed, we have found similar calls for unity without justice at other inflection points in U.S. history, most recently around the coup on Jan. 6.

In the immediate aftermath of the attack on the Capitol, as Democrats in Congress began discussing impeachment, House Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy released a statement claiming that holding Donald Trump to account through another impeachment, “will only divide our country more.” Invoking Abraham Lincoln, McCarthy continued, “We must call on our better angels and refocus our efforts on working directly for the American people. United we can deliver the peace, strength, and prosperity our country needs. Divided, we will fail.”

Florida Senator Marco Rubio — who a few months earlier had encouraging words for a mob of Trump supporters that had swarmed a Biden campaign bus, causing the campaign to cancel an event — tweeted on Jan. 10, “Biden has a historic opportunity to unify America behind the sentiment that our political divisions have gone too far. But instead he decided to … use this terrible national tragedy to try and crush conservatives or anyone not anti-Trump enough.”

In this more recent time, as in the 19th century, the “we” that was meant to be unified was once again intended to reinscribe white supremacy, to remind everyone who is, and isn’t, truly seen as a real American. As Mekishana Pierre, a Black woman, wrote as calls for the nation to come together piled up by Trump supporters who took no issue with his racist language, with his horrific immigration policies, with his Muslim Ban, with his shout-outs to the Proud Boys, “Why is it that the price of unity has always been at the cost of our freedom? Why is it the job of those who are constantly denied their humanity to compromise?”

RELATED: PBS docs depict Frederick Douglass’ and Harriet Tubman’s paths of freedom, faith

Now, as in the post-Civil War era, we must ask: Who benefits from sweeping harm under the rug? Whose interests are further marginalized when that happens? Any time unity and forgiveness are used as keywords at times of great tension, we must stop and ask: Unity at the expense of whose justice? Forgiveness without demanding what repentance?

The January 6th Committee has a historic opportunity to show that actions have consequences. The subpoena of Trump is a tremendous start. But it must not be the end.

Rabbi Danya Ruttenberg. Courtesy photo

And, indeed, the path forward for our country may well depend on the decision to show us that “justice for all” means something at last.

(Rabbi Danya Ruttenberg is scholar-in-residence at National Council of Jewish Women and the author, most recently, of “On Repentance and Repair: Making Amends in an Unapologetic World,” from which this op-ed is adapted. The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily reflect those of Religion News Service.)