(RNS) — John Schmalzbauer, a religious studies professor at Missouri State University, said religion has long drawn tourists to Branson, Missouri, even before the city became known as a popular vacation spot for conservative Christians.

The natural beauty of the Ozarks was seen as a “bucolic, pastoral retreat from all that ails modern civilization,” he said.

In the early 1900s, church groups like the YMCA and YWCA, as well as several other denominations, established camps in the area, including one known as Presbyterian Hill, which was later sold to the Missouri Baptists. Christian minister Harold Bell Wright’s bestselling novel, “The Shepherd of the Hills,” paints the Branson area as a spiritual refuge as well, a place where people lived out their faith rather than just talking about it in church.

“The idea was that you can get away from the hustle and bustle of modern life,” he said.

In the early days, there was more theological and social diversity in the area than there is today in Branson. A now-shuttered YMCA camp in Hollister, Missouri, right next door to Branson, hosted Black leaders like Howard Thurman and George Washington Carver and integrated camps for young people in the 1920s at a time when the local community was still segregated. That camp was heavily influenced by the Christian social gospel, which led to criticism from a conservative, claiming the camp was promoting socialism and condemning nationalism.

John Schmalzbauer. Photo courtesy of Missouri State University

“There should be a state law whereby every teacher and lecturer should be forced to take a pledge of allegiance to the flag and to the constitution before he or she would be allowed to talk,” an American legion leader named Curtle C. Gates told the Springfield Press in 1932.

Wright, whose 1917 bestselling novel led tourists by the thousands to visit Branson and inspired a long-running outdoor theater production that now includes dinner and ziplines, also promoted the social gospel, albeit the more conservative variety of the early 1900s, with themes of redemption and a belief that actions to help those in need were more important than theological niceties.

Schmalzbauer said Branson has promoted itself as a faith and family tourist spot and walks a fine line between appealing to a conservative crowd while not turning people off with too much politics. More extreme forms of Christian nationalism can be found around the edges, he said, pointing to controversies over Dixie Outfitters, a strip mall store on Branson’s main drag that sells Confederate flags and MAGA gear.

In recent years, he said, political leaders have seen Branson as friendly to conservatives.

“100 years ago, it was much more like Chautauqua or Martha’s Vineyard,” Schmalzbauer said. “Now there is a vast difference. No Florida governor would be sending a planeload of immigrants to Branson today.”

RELATED: In Branson, God and Country serves as red, white and blue comfort food

Still, more extreme forms of Christian nationalism have found a home in the Ozarks and in Southeastern Missouri. Schmalzbauer said a number of people who stormed the U.S. Capitol came from nearby Springfield, Missouri, and pointed to a series of disputes over mask mandates in cities and towns outside of Branson.

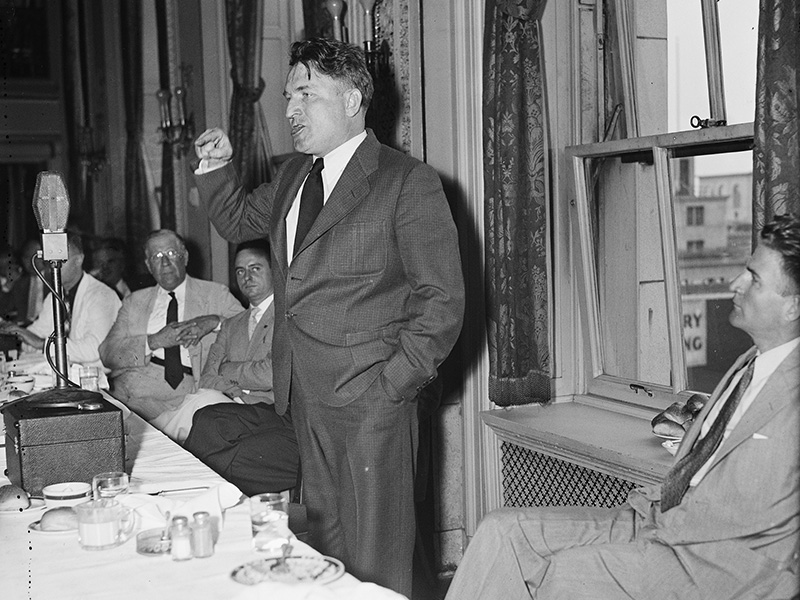

Gerald Lyman Kenneth Smith speaks against the New Deal in Aug. 1936. Photo courtesy of the Library of Congress/Creative Commons

Perhaps the most famed Christian nationalist in the Ozarks was the Rev. Gerald Lyman Kenneth Smith, a Disciples of Christ minister, founder of the American First Party and the Christian Nationalist Crusade and publisher of the “Cross and the Flag,” known for his virulent antisemitism and racism. In the 1960s, he built “Christ of the Ozarks,” which is a massive statue of Jesus, and a Holy Land replica and created an annual outdoor Passion play, all of which remain popular attractions.

For years, Smith, who got his start in politics as an ally of notorious Louisiana Governor Huey Long, boasted of antisemitic themes in his version of the Passion play and advocated that Black and Jewish Americans should be deported. The mission of the Christian Nationalism Crusade was to “preserve America as a Christian nation being conscious of a highly organized campaign to substitute Jewish tradition for Christian tradition.”

Smith died in 1976. The crusade folded soon afterward.

In his obituary, The New York Times reprinted a quote from Smith about how he used “religion and patriotism” to attract followers “hook, line and sinker.”

“I’ll teach them how to hate.”

A variety of attractions along the strip in Branson, Mo., on Aug. 26, 2022. RNS photo by Kit Doyle

RELATED: Why Christian Nationalism is un-Christian

This story was produced under a grant from the Stiefel Freethought Foundation