(The Conversation) — It’s one of the most famous moments in modern Catholicism: the apparition of Our Lady of Fatima. The Virgin Mary allegedly appeared to three Portuguese children in 1917, when much of the world was engulfed in World War I. Over a series of six appearances, Mary emphasized to these young shepherds that to bring peace, they should pray the rosary every day.

Devotion to the rosary already had a centuries-old history, and the Marian apparition at Fatima only deepened it. So what is a rosary, and why is it so important to many Catholics?

Centuries of meaning

As an archivist and associate professor for the University of Dayton’s Marian Library, I curate a collection of artifacts that illustrate many forms of popular devotion to the Virgin Mary, including nearly 900 unique rosaries. Each one tells a story of the people who owned them and how rosaries have evolved.

The word “rosary” refers to a set of prayers in the Catholic Church as well as a physical object. While praying the rosary, Catholics use a set of beads or knots to count and keep track of the prayers. Prayer beads as physical counting tools are quite common in several religions, including Islam, Hinduism, Buddhism and Jainism.

The exact origins of the rosary are debated. Many theologians believe it was at least popularized by St. Dominic de Guzman, a Spanish mystic and priest who allegedly received a vision in 1208 of the Virgin Mary in which she presented him with the rosary.

The Catholic Church celebrates the Feast of Our Lady of the Rosary on Oct. 7 each year – previously known as the Feast of Our Lady of Victory to commemorate a Christian victory in a naval battle in 1571. Soon after, Pope Gregory XIII changed the title of the holy day, and now the entire month of October is dedicated to the rosary.

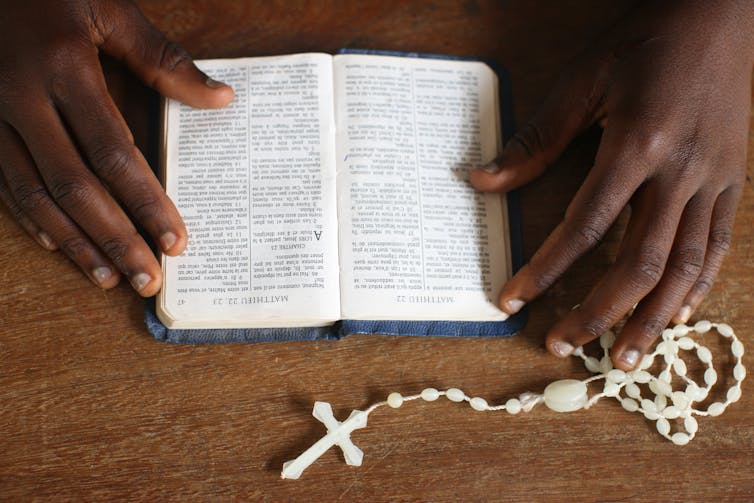

Rosaries have been used for centuries, but their exact origins are unclear.

Pascal Deloche/Stone via Getty Images

One prayer per bead

To pray the rosary, a person will begin by holding the crucifix, make a sign of the cross over their chest and recite the Apostles’ Creed, which lays out the basics of Christian faith — such as that Jesus is the son of God and rose from the dead.

Generally, a rosary will contain five groups of 10 beads each, known as a decade. When touching each of these beads, the user will recite a Hail Mary prayer. At the completion of each decade is a slightly larger bead, which is a cue to recite the Lord’s Prayer — another of the most important prayers in Christianity — and to meditate on one of the 20 mysteries, significant events in the life of Jesus and Mary.

The decade is completed by saying the Glory Be to the Father prayer, and after completing all five decades, the user recites the Hail, Holy Queen prayer to Mary. The U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops outlines detailed instructions, including a diagram showing the different parts of the rosary and the accompanying prayers.

The rosary can be recited alone, or in groups. Some Catholics pray the rosary daily, and many recite it to thank God or to ask for intercession, such as healing or protection for a loved one.

Shells and seeds

The Marian Library’s collection demonstrates how the rosary as an object can be very personal and also engage different senses as people pray. Some are very fragrant, such as those made from peach pits. Some are souvenirs brought back from particular shrines, such as ones from the Sanctuary of Our Lady of Lourdes in France, which contain drops of holy water from its spring. Other rosaries glow in the dark or are made from birthstones. Many have significance to a particular region, such as rosaries made from a grain called Job’s tears, which are popular in Cajun regions of Louisiana.

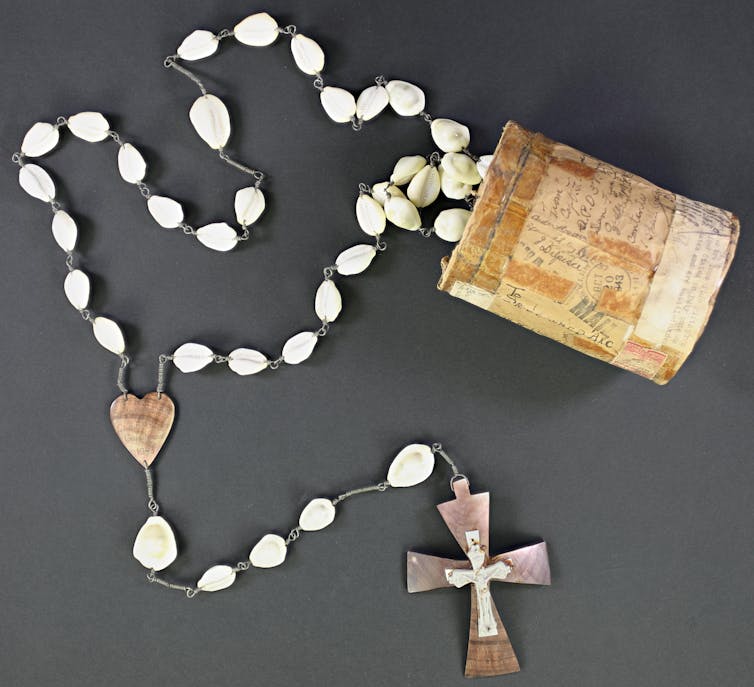

There are rosaries of natural materials such as seeds, olive pits or even seashells – including one crafted out of cowrie shells and paper clips. A National Guard chaplain stationed in Guadalcanal, site of a key series of battles between U.S. and Japanese troops, mailed it to his sister, a nun, in 1943 with the message “pray for me.”

A rosary sent to Ohio from Guadalcanal during World War II.

Ryan O’Grady/The Marian Library, University of Dayton, CC BY-NC-SA

Then there is a photograph of a colorful pile of plastic rosaries – these ones taken from Latin American migrants and others seeking asylum at the southern U.S. border. While working as a janitor at a U.S. Customs and Border Protection processing facility, Tom Kiefer used photography to document migrants’ personal items deemed nonessential and confiscated or thrown into the trash.

Today and tomorrow

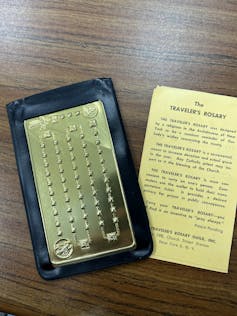

The Traveler’s Rosary from the Father John T. Arsenault Rosary Collection.

The Marian Library, University of Dayton, CC BY-NC

Several new rosary inventions in the 21st century attempt to make praying the rosary convenient for even the busiest person. The Traveler’s Rosary, designed by the Archdiocese of New York, is made of a flat piece of metal with raised beads. It also comes with a case that commuters can use to hold a transportation ticket. The Recording Rosary is also meant to make praying more convenient: The beads are placed on a dial, and a small arrow points to the proper place, so the person praying can resume where they left off after an interruption. The rosary also emits a subtle sound at the completion of each decade.

The rosary itself, and the practice of praying it, continues to evolve today. In 2019 a church group launched the “Click to Pray eRosary”: a wearable device that connects with a free phone app to help users learn to pray the rosary. The developers explain that the device is “aimed at the peripheral frontiers of the digital world where the young people dwell.”

Whether made out of glass beads with holy water or of fragrant dried rose petals pressed into beads, the rosary reflects the myriad ways Catholics can practice their devotion.

(Kayla Harris is a librarian/archivist at the Marian Library and an associate professor at the University of Dayton. The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily reflect those of Religion News Service.)