(RNS) — The embattled U.S. Rep George Santos of New York claims that he’s not Jewish, but only “Jew-ish.” That distinction might seem to disqualify him from automatic Israeli citizenship under the country’s “Law of Return,” which offers immediate citizenship to all Jews. But the truth is you don’t have to be Jewish to be included.

The law, enacted in 1950, assumed that Jewish status would be determined by traditional Jewish religious law, or Halakha. But in 1970, it was expanded to encompass not only Jews as defined by the Talmud but any child or grandchild of a Jew, even if his or her other grandparents were not Jewish. It also included any spouse of a Jew, spouse of a child of a Jew or spouse of a grandchild of a Jew.

The amended law also extended Jewish status to those converted to Judaism by the Conservative or Reform Jewish movements — and, presumably the Reconstructionist and Humanistic ones. (The latter movement requires only “cultural identification” for membership so Santos might still be in luck).

The very existence of the Law of Return puzzles many of us Americans, whose constitutionally secular republic officially favors no faith when conferring citizenship. But many countries have official religions (15, including Denmark and Greece, that are Christian; at least 20 that are Muslim) and some offer special treatment to those who subscribe to the established faith.

For Israel, which considers itself not only a Jewish state (the world’s only one) but a refuge for every Jew on Earth, the special treatment is particularly urgent. The countless persecutions of Jews, in particular the Holocaust that shortly preceded Israel’s founding in 1948, were the impetus for her enacting the Law of Return.

On the other hand, the Law of Return doesn’t define who is Jewish and who isn’t — for many Jews in Israel, and certainly to the Orthodox parties and the Chief Rabbinate, the Halakhic definition is the only pertinent one.

So why, then, did Israel’s religious parties demand, as part of their deal to join the government of Israel’s new (and old) prime minister Benjamin Netanyahu, that Israel tighten the Law of Return by erasing its grandchild clause?

The answer is that, while Orthodox principles don’t allow them to consider a non-Jewish “Law of Return” citizen to be Jewish, other Israelis may assume that if a fellow citizen immigrated through the Law of Return, he or she must be Jewish. That is a recipe for increased intermarriage between Jews and non-Jews, which would fuel further polarization within Israeli society and radically affect the demographics of the Jewish state.

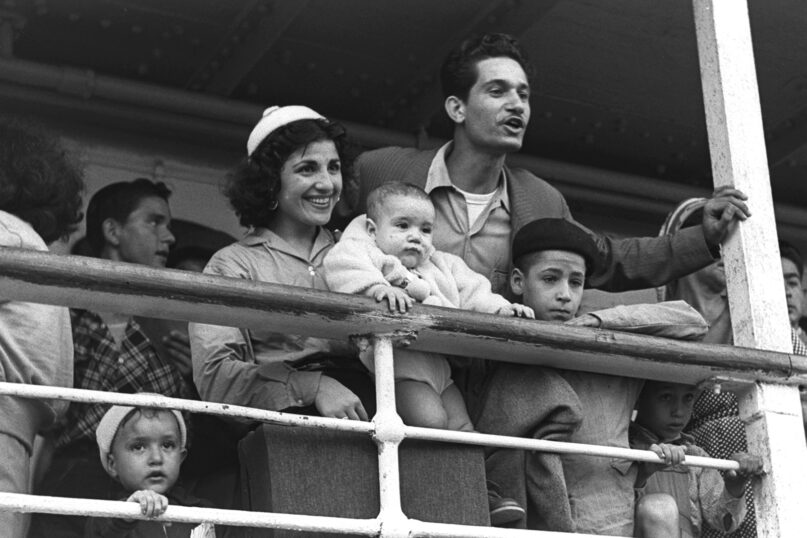

That has already happened to an extent. A large influx in the 1990s and early 2000s of hundreds of thousands of immigrants from the former Soviet Union seeking economic advancement and claiming a Jewish antecedent became citizens under the Law of Return. According to the Israeli Central Bureau of Statistics, more than a quarter of the immigrants who arrived in Israel were not considered Jewish under Halakha.

Last year, Moscow’s invasion of Ukraine and crackdowns at home yielded another 70,000 immigrants from both countries, according to year-end figures released by the Jewish Agency.

Many American Jews, of course, regard intermarriage as an opportunity, not a problem. But to those who consider the continuity of the Jewish people of utmost importance, it is a threat to the integrity and unity of the Jewish community. Which is why the Israeli Immigration Policy Center, a lobbying group that often seeks to limit immigration, has endorsed doing away with the grandchild provision.

Some American Jews claim that eliminating the grandchild provision will prevent people from becoming Israeli citizens, but their worries are misplaced. What the Law of Return offers is immediate, automatic citizenship, as well as some attendant economic perks. Anyone of any faith, ethnicity or national origin can still become a citizen of Israel through the regular naturalization process, similar to the way foreigners become citizens of the U.S. or other countries.

To be sure, instant citizenship is a more attractive option than going through a naturalization process. But it shouldn’t be too much to ask non-Jewish, would-be Israelis to understand the history and import of the Law of Return and go the normal route.

(Rabbi Avi Shafran is director of public affairs for Agudath Israel of America, a national Orthodox Jewish organization. He blogs at rabbishafran.com. The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily reflect those of Religion News Service.)