(RNS) — For a quarter century, the Rev. Barry W. Lynn dedicated himself to maintaining a firm line between church and state.

In the third of three volumes of his new memoirs, “Paid to Piss People Off,” Lynn lays out his rationale: “When all is said and done, I have never known a single soul saved nor a single crime prevented by government force-feeding religion.”

Before leading Americans United for Separation of Church and State from 1992 to 2017, he helped his denomination defend Vietnam War resisters and worked for the American Civil Liberties Union as a self-declared “irritant” countering a Reagan-era pornography commission.

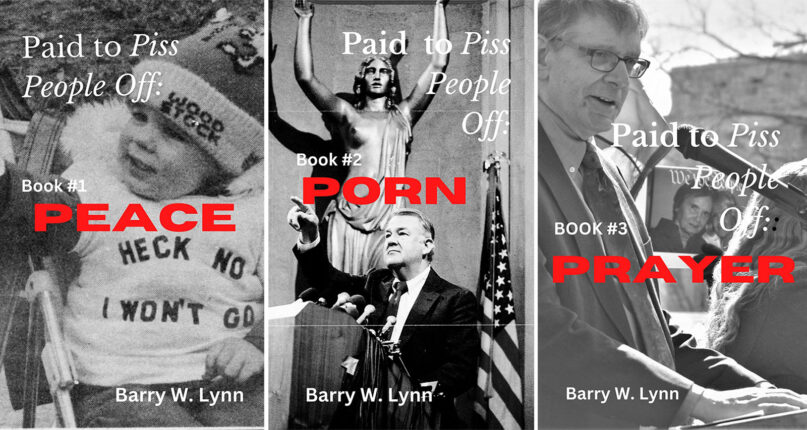

An oft-called-on talking head, Lynn, a lawyer as well as a United Church of Christ minister, was never shy about presenting his side of culture-war debates on CNN or Fox News. His memoirs’ three volumes are titled with characteristic bluntness: “Peace,” “Porn” and “Prayer.”

“My advice to people who want to change the world is to never give up trying to do it, and there are going to be setbacks or there are going to be victories; and the second: never forget those people that are behind the causes,” he said in an interview.

RELATED: Barry Lynn looks back on 25 years of separating church and state

“It is people who are hurting, people who are outcasts, that appealed to me. I just wanted to do something of value for people who didn’t have much support before.”

Barry Lynn in 2010. Photo courtesy of AU

Lynn, 74, talked with Religion News Service about his favorite fights, his “mistake” of supporting the Religious Freedom Restoration Act and his hopes for the Supreme Court.

The interview was edited for length and clarity.

You have objected to public displays of the Ten Commandments, sought enforcement of IRS rules against churches endorsing political candidates and declared there really isn’t a “War on Christmas.” What do you consider most important among your church-state separation efforts?

I think the most important thing that I helped to do were the (2005) creationism case with (federal judge) John Jones (rejecting intelligent design as a high school science course). Now, ironically, Jones is the president of the college, Dickinson College, that my wife and I attended. Also the pentacle quest, the effort to make sure that Wiccans and pagans could obtain a symbol, the pentacle, on the gravestones in federal and state cemeteries. Both of those were just, to me, the high points of what it takes when you get a team of people with a goal and then succeed at that goal.

What was so important about the creationism case?

A small town near where I grew up in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, decided they would introduce creationism in their public high school. A local church had donated a huge number of books called “Of Pandas and People,” which is a so-called creation science book. And they instructed students about how they should learn this alternative to evolution. When all was said and done, Jones wrote the most spectacular, detailed explanation of why it was unconstitutional to present creationism like this as if it was an alternative to science.

You write that church-state separation became your issue before you even left college.

The Rev. Barry Lynn in 2015. Photo by Tim Ritz

I had a roommate in college, and one day he said, “Oh, I’m spending spring vacation in London.” And I thought, “Oh, that must be fun.” And he said, “No, it’s not gonna be fun, because my girlfriend is pregnant and we have to go to England to get an abortion.” And that was the very first time that it came to my attention that powerful religious groups could impose their will on all kinds of people, just by the clout that they had with state legislatures. So when people say, well, what’s the issue? It was that issue that got me involved in church-state separation.

After theology school, you were a pastor for a time. Why did you choose a different path than a pastorate for most of your life?

I went to theology school, Boston University, in part because Martin Luther King had gotten his master’s degree there. I enjoyed the classes and the courses but I mainly enjoyed the practicums, the things you could do in order to do some kind of service. I did serve as a pastor in one of those churches in New Hampshire that only has enough people to stay open during the summer when summer travelers can also go to it, and I enjoyed it.

But then I got an opportunity to work for the United Church of Christ in Washington. Right behind (the job interviewer) was a poster by (pop artist) Sister Corita (Kent) that said, if Jesus comes again, he better come in the shape of a loaf of bread. And I thought, “Man, that’s my kind of religion.”

You helped craft the 1993 Religious Freedom Restoration Act, and a range of religious groups came together for that. How unusual was that at the time?

It was unusual. And if I were looking back at it, the biggest mistake I ever made was supporting that, first at the ACLU and then at Americans United. It was a solution in search of a problem. And it has now been used as one of the greatest weapons against reproductive choice and LGBTQ rights in the country. Everybody has now decided that if you have a religious claim to make, it kind of trumps anything else, and there are bad decisions by the Supreme Court already. And I suspect by June there’ll be even worse ones that essentially say in part because of RFRA, that if you don’t want to serve a gay couple, as long as your motivation is “my religion tells me I shouldn’t do it,” they will win.

The Rev. Barry Lynn, center, speaks outside the Supreme Court in 2009. Journalists Nina Totenberg, left, and Pete Wlliams, right, await answers. Photo by Maria Matveeva

When RFRA first came out, the winners were Native Americans. They were able to worship the way they wished with peyote, a hallucinogenic cactus.

Yeah, there were two good uses. One was with Native Americans and the other was with prisoners, and finally with Sikhs, and Muslims who wanted to wear a beard, or a head covering, and either the prison or the firefighters union would say, “Oh, you can’t do that.” This was a solution for them.

You labeled the faith-based initiative at the White House, which has existed since George W. Bush’s term, as a “mess.” Was there anything good about it in your eyes?

I used to refer to it as the worst idea since they decided to take King Kong off of Skull Island and move him to New York. I still believe that.

You speak of separation of church and state having “fared poorly” at the Supreme Court since your retirement and the appointment of three justices by President Trump. What hope do you have for the future of church-state separation?

I do have hope, because I do think, eventually, the Democratic Party will speak with one voice and do one of two things: They will either expand the number of justices on the court, or they will give people in the District of Columbia voting rights, and then there will be automatically two senators in D.C., and either one would shift the balance enough so that people can go in and change (the number of justices). Maybe more is better.

The Rev. Barry Lynn speaks at a rally outside the Supreme Court on March 23, 2016, in Washington, D.C. Photo courtesy of AU