(The Conversation) — Six adults were killed March 9, 2023, in Hamburg, Germany, in what police described as a “rampage” after an evening religious service. Several others were wounded during the attack at a Jehovah’s Witness center, called a Kingdom Hall, including a woman who lost her pregnancy. The suspected shooter was reported to be a former member of the religious group.

The attack has put a focus on the religious group, which has some 8 million members across 240 countries. In Germany, more than 170,000 Jehovah’s Witnesses are associated with 2,020 congregations, according to the organization’s records.

In many countries, Jehovah’s Witnesses are known for their outreach work, going door to door or standing in public areas to try to distribute religious material. But many people are unfamiliar with their beliefs, and when the group makes headlines, it is often for reasons related to persecution abroad.

So who are they?

A man crosses himself outside the Jehovah’s Witnesses building in Hamburg where several people were killed during a shooting March 9, 2023.

Georg Wendt/picture alliance via Getty Images

Early history

The story of Jehovah’s Witnesses begins in the late 19th century near Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, with a group of students studying the Bible. The group was led by Charles Taze Russell, a religious seeker from a Presbyterian background. These students understood “Jehovah,” a version of the Hebrew “Yahweh,” to be the name of God the Father himself.

Russell and his followers looked forward to Jesus Christ establishing a “millennium” or a thousand-year period of peace on Earth. This “Golden Age” would see the Earth transformed to its original purity, with a “righteous” social system that would not have poverty or inequality.

Russell died in 1916, but his group endured and grew. The name “Jehovah’s Witnesses” was formally adopted in the 1930s.

Early Jehovah’s Witnesses believed 1914 would be the beginning of the end of worldly governments, which would culminate with the Battle of Armageddon. Armageddon specifically refers to Mount Megiddo in Israel, where some Christians believe the final conflict between good and evil will take place. Jehovah’s Witnesses, however, expected that the Battle of Armageddon would be worldwide, with Jesus leading a “heavenly army” to defeat the enemies of God.

They also believed that after Armageddon, Jesus would rule the world from heaven with 144,000 “faithful Christians,” as specified in the Book of Revelation. Other faithful Christians would be reunited with dead loved ones and live on a renewed Earth.

Over the years, Jehovah’s Witnesses have reinterpreted elements of this timeline and have abandoned setting specific dates for the return of Jesus Christ. But they still look forward to the Golden Age that Russell and his Bible students expected.

Given the group’s belief in a literal thousand-year earthly reign of Christ, scholars of religion classify Jehovah’s Witnesses as a “millennarian movement.”

What are their beliefs?

Jehovah’s Witnesses deny the idea of the Trinity. For most Christians, God is a union of three persons: Father, Son and Holy Spirit.

Instead, Jehovah’s Witnesses believe that Jesus is distinct from God – not united as one person with him. The “Holy Spirit,” then, refers to God’s active power. Such doctrines distinguish Jehovah’s Witnesses from mainline Christian denominations, which hold that God is “triune” in nature.

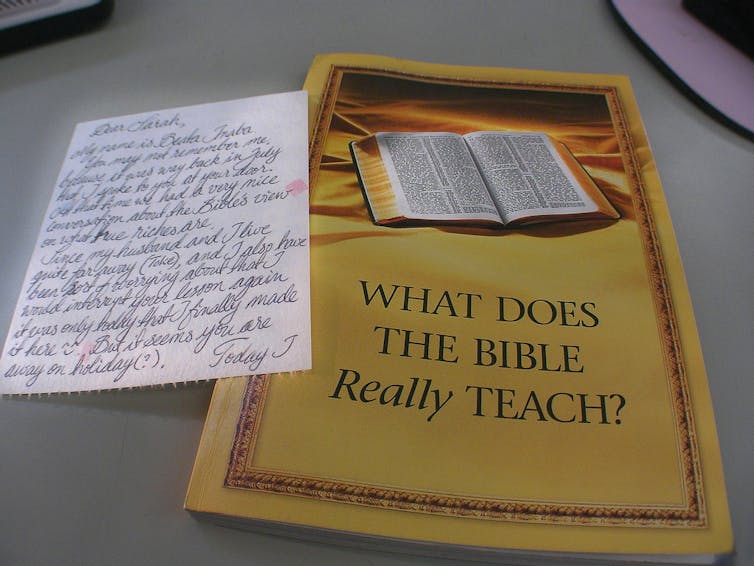

Jehovah’s Witnesses spend a substantial amount of time on Bible study and evangelizing door to door.

Jonathan Haynes, CC BY-SA

But like other Christian denominations, Jehovah’s Witnesses praise God through worship and song. Their gathering places are called “Kingdom Halls,” which are ordinary-looking buildings – like small conference centers – that have the advantage of being easily built. Inside are rows of chairs and a podium for speakers, but little special adornment. Jehovah’s Witnesses are best known for devoting a substantial amount of time to Bible study and door-to-door evangelizing.

Their biblical interpretations and missionary work certainly have critics. But it is the political neutrality of the group that has attracted the most suspicion.

Jehovah’s Witnesses accept the legitimate authority of government in many matters. For example, they pay taxes, following Jesus’ admonition in Mark 12:17 “to render unto Caesar what is Caesar’s.”

But they do not vote in elections, serve in the military or salute the flag. Such acts, they believe, compromise their primary loyalty to God.

A history of persecution

Jehovah’s Witnesses have no political affiliations, and they renounce violence. However, they make an easy target for governments looking for internal enemies, as they refuse to bow down to government symbols. Many nationalists call them “enemies of the state.”

As a result, they have often suffered persecution throughout history in many parts of the world.

Jehovah’s Witnesses were jailed as draft evaders in the U.S. during both world wars. In a Supreme Court ruling in 1940, school districts were allowed to expel Jehovah’s Witnesses who refused to salute the American flag. Through subsequent legal battles in the 1940s and 1950s, Jehovah’s Witnesses helped expand safeguards for religious liberty and freedom of conscience both in the United States and Europe.

In Nazi Germany, Jehovah’s Witnesses were killed in concentration camps; a purple triangle was used by the Nazis to mark them. In the 1960s and 1970s, dozens of African Jehovah’s Witnesses were slaughtered by members of The Youth League of the Malawi Congress Party for refusing to support dictator Hastings Banda. Many Witnesses fled to neighboring Mozambique, where they were held in internment camps.

The ‘cult’ label

Police in Germany have said the 2023 shooting was most likely committed by a lone individual who did not leave the organization “on good terms,” although they have not released information about a possible motive.

At times, disputes between members and ex-members have revolved around criticism over practices such as refusing blood transfusions and “disfellowshipping” members who do not repent for committing what the group considers serious sins.

In popular culture, Jehovah’s Witnesses are sometimes portrayed as members of a “cult,” which has made them a convenient target for persecution and multiple forms of violence. As I and other religion scholars have written, however, that word is very difficult to define – and tends to lead to stereotypes, rather than nuanced understanding.

This is an updated version of an article originally published on May 4, 2017.

(Mathew Schmalz, Professor of Religious Studies, College of the Holy Cross. The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily reflect those of Religion News Service.)

![]()