(RNS) — In late 2008, my mother was diagnosed with breast cancer.

Over the next 18 months, her condition would deteriorate, and despite our prayers, she passed away at 54, just three weeks before Mother’s Day.

Since her death, I’ve come to view Mother’s Day as a bittersweet commemoration. As much as I celebrate my wife and all of the mothers and grandmothers in my family and extended family, the person who gave me life and who, for all intents and purposes, was my best friend for much of my youth is not here.

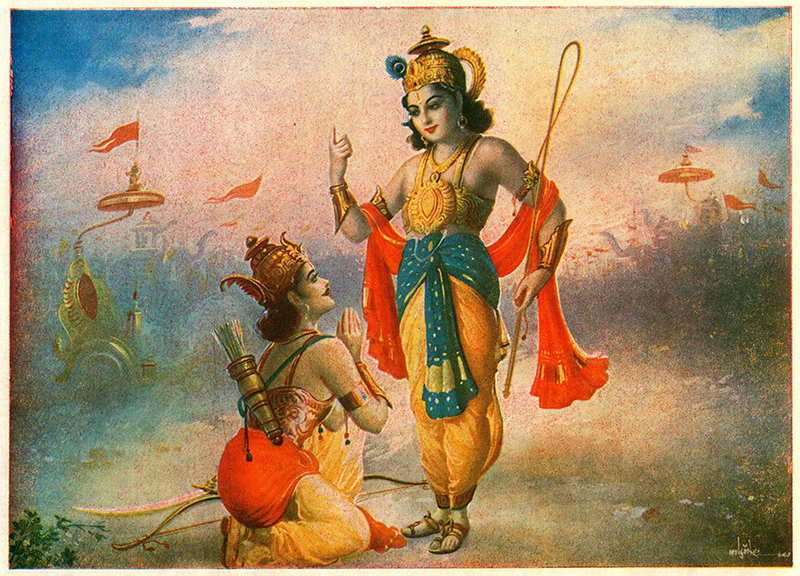

My grief, however, bumps up against my unconditional belief in Hindu philosophy, which presents those who grieve with a paradox. In the Bhagavad Gita — one of Hinduism’s most important sacred texts and one that inspired Mahatma Gandhi, the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. and Nelson Mandela — Lord Krishna urges Arjuna not to weep for those who have died.

Krishna reminds Arjuna that the soul never dies, and that it is indestructible, journeying from one physical form to another until it ultimately achieves moksha, or liberation. In the weeks after my mother passed, numerous Hindu priests and lay scholars noted that her intense suffering in her last weeks and days likely meant her soul had achieved liberation. She would no longer need to be reborn.

Arjuna, left, and Lord Krishna. Image by MahaMuni/Wikipedia/Creative Commons

The priests noted that karma, or the consequences of one’s actions, does not always materialize in one’s lifetime. Therefore, my mom’s suffering may have been a way for her to dissolve all the karma from negative actions in previous lives, especially since she lived her life dharmically and devoted to the divine.

Embedded in the idea of reincarnation and the relative transience of our physical forms is this teaching that grief is a symptom of one’s continued attachment to the material world. The truly wise, Krishna tells Arjuna, do not grieve, for they know the soul exists regardless of what physical form it takes. In essence, Krishna asks Arjuna, why weep for something that is always there and will always continue to be?

While I try to find comfort in that idea, reincarnation and liberation don’t necessarily make me miss my mother any less. Even as numerous Hindu scriptures urge detachment from the material world as one grows older, grief is a powerful emotion to let go of.

I think about my mother whenever I hold my son, wondering what she would say to him as his paatti, or grandmother. I ask my mother in my prayers if I am doing my best in living a dharmic, or righteous, life. Even if her soul has ascended, I still am tied to the deepest and most visceral love for my mother.

My efforts to navigate the disconnect between the beauty and wisdom of Hindu philosophy and my unbidden and almost palpable experience of grief have led me nowhere, and I have long since given up. I appreciate the ultimate goal of our souls’ journey, but I also miss my mother every day and still pray as hard as I can to be able to spend just five more minutes with her.

Is that a contradiction? As one Hindu chaplain told me a number of years ago, “It’s called being human.”

(Murali Balaji is a journalist and a lecturer at the Annenberg School for Communication at the University of Pennsylvania. He is the editor of “Digital Hinduism” and author of “The Professor and the Pupil,” a political biography of W.E.B. Du Bois and Paul Robeson. The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily reflect those of Religion News Service.)