RALEIGH, N.C. (RNS) — On Yom Kippur, the holiest day of the Jewish year, Shana Silverstein and her daughter, Talia, will attend services at Beth Meyer Synagogue, as they usually do on this day.

Silverstein’s husband, Tom Barbieri, will be there, too. But as a non-Jew, not drawn to religious services, he’ll be patrolling the building as part of the synagogue’s security team.

Silverstein and Barbieri are among the growing ranks of intermarried synagogue members. She is Jewish. He grew up Catholic, though he has been non-practicing since his early 20s. Both have been full members of the large Conservative synagogue in North Carolina’s capital since 2007.

Their two children (a son is in college) have grown up in the synagogue, celebrated the bar and bat mitzvah rite of passage and identify as Jews. Silverstein is active on several committees and serves on the board. Barbieri can be found on Saturday’s security detail on average once a month.

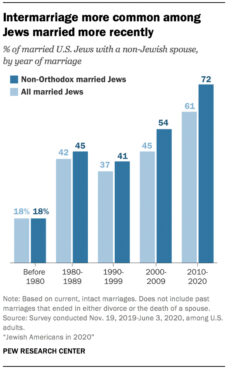

In the past decade, 61% of American Jews married non-Jewish spouses, according to a 2020 Pew report, a huge spike over past decades where it hovered around 45%. (Pew’s more recent surveys suggest the rate of Jewish intermarriage in the past few years may be slowing.) While many of those intermarried couples, like a growing number of Jewish couples, have no institutional Jewish attachments, the liberal Jewish movements have come a long way in welcoming non-Jewish spouses and encouraging their involvement.

Tom Barbieri, from left, Shana Silverstein, and their children, Talia and Liam, pose on a glacier while vacationing in Iceland in July 2022. Photo courtesy Shana Silverstein

“My husband is the most supportive partner of our children being Jewish and of practicing, culturally and religiously, their Jewish heritage,” said Silverstein, a veterinarian who lives in Wake Forest, North Carolina, with Barbieri, an engineer for a semiconductor company. “And in many ways, I found him a more supportive partner to that than the Jewish people I had dated before him.”

Beth Meyer Synagogue changed its constitution and bylaws in the past decade to allow non-Jewish spouses to be full members and to serve on the board of trustees. During Rosh Hashana services last week, a non-Jewish spouse who had served on the synagogue’s board gave the annual fundraising appeal.

The synagogue also added some rituals that non-Jews may perform, such as carrying the large Torah scroll and handing it to the bar mitzvah child, as Barbieri did during his daughter’s bat mitzvah service three years ago.

Eric Solomon, Beth Meyer’s rabbi, said his attitude to intermarried couples can be summed up in a few words: “You marry us, you’re part of us.”

“Obviously some don’t want to participate — that’s fine, and we respect that,” said Solomon. “But for those that do, and that is the majority, we are elated to have them participate in the community as a couple.”

The rabbi estimated that about 15% of its 500 member families are intermarried.

RELATED: Ahead of High Holidays, US Jewish leaders stress need for security vigilance as antisemitism surges

Last week, Vice President Kamala Harris, a Black Baptist, and her husband, Doug Emhoff, a white Jew, were spotted attending Rosh Hashana services at Adas Israel, Washington, D.C.’s prominent Conservative synagogue.

Vice President Kamala Harris leans in to kiss her husband, Doug Emhoff, after she spoke during an event in Washington, Friday, June 23, 2023. (AP Photo/Susan Walsh)

They are only the latest example of a sea change in what used to be called interfaith marriage. It is now typically referred to as “intermarriage,” because increasingly, one partner in such marriages doesn’t necessarily have a faith. Religious intermarriage, which once carried a stigma, is now commonplace and is reshaping the contours of Jewish belief, practice and community.

Jews, who make up only 2.4% of U.S. adults, initially greeted the accelerated pace of intermarriage with panic. Many Jewish leaders feared intermarriage was a straight path to full assimilation and a complete abandonment of Jewish life. Many Orthodox Jews still feel this way.

But as Keren R. McGinity, interfaith specialist with the United Synagogue of Conservative Judaism, now sees it, intermarriage is not a linear process that inherently leads people to become less Jewish or to abandon the faith.

“Qualitative studies about intermarriage illustrate how someone’s Jewish identity can actually become stronger,” she said. “Someone may intermarry and then actually become, quote, ‘more’ Jewish.”

Over the last few decades, Jewish denominations have slowly been amending their policies to draw in intermarried couples and, in McGinity’s words, offer “more honey, less vinegar.”

In 1983, the Reform movement held that a person is Jewish if either parent was Jewish (not just the mother, as Jewish tradition has mostly held). It later dropped its ban on rabbis officiating at marriages between Jews and non-Jews. In 2015, the smaller Reconstructing Judaism movement announced it would accept candidates for the rabbinate whose spouses were not Jewish. Hebrew College, a nondenominational seminary in a Boston suburb, also changed its policies and admits rabbinical students in mixed marriages.

The Conservative movement, the second-largest in American Jewish life, still does not allow its rabbis to officiate at interfaith marriages, though many of its rabbis would like to. Solomon, Beth Meyer’s rabbi, is one of them.

“I’m increasingly feeling like I am making a mistake by not grabbing that opportunity to bring (couples) closer to the Jewish people,” Solomon said.

“Intermarriage more common among Jews married more recently” Graphic courtesy Pew Research Center

While Solomon is not ready to step outside the Conservative movement rules, several nonprofit organizations have risen up in the past decade dedicated to helping Jewish and non-Jewish couples find a rabbi who will marry them.

One such organization, 18 Doors, has a referral service of rabbis willing to officiate at such marriages, plus wedding planning guides that incorporate Jewish traditions.

The organization’s mission is to support intermarried couples and make them feel included. It recently offered an online event, “How to celebrate the High Holidays in secular and cultural ways.” Denise Handlarski, a secular rabbi married to a non-Jew who led the session, tried to empower some two dozen Zoom participants to go ahead and practice in their own way.

“Lots of us have felt that sting of being not quite included or made to feel you’re not quite the right fit,” she told participants. “So I really, really care that you hear that you are more than welcome to engage with Judaism. It’s yours.” Or, as she added, “Jew it your way.”

One reason the Jewish community is making way for intermarried couples is simple demographics: The Jewish population has not shrunk over the past decade. In fact, it has grown — from 6.7 million in 2010 to 7.5 million in 2020, according to Pew.

And while intermarried couples’ involvement in the Jewish institutional and communal life remains low on a host of measures, there’s some evidence that outreach efforts are making a difference for Jewish continuity.

For example, the majority of children of intermarried couples who are raised as Jews identify as Jews, said Leonard Saxe, director of the Cohen Center for Modern Jewish Studies at Brandeis.

“The future of the Jewish people turns on whether we’re going to educate the children of one, as well as two, Jewish parents,” Saxe said. “That’s what’s happened in America, and it has led to an increase in the population.”

For Silverstein and Barbieri, who met as graduate students at Cornell University, the decision to raise their kids as Jewish came even before they married.

Barbieri, who is 49, said his connection to his Catholic faith ended in his early 20s.

“Since then I’ve really had no need to go back,” he said. “I don’t feel the need.”

Silverstein, who grew up culturally Jewish, began growing more committed to her faith in her teens. By the time she met Barbieri she knew she wanted to belong to a synagogue and to raise her children in her faith.

The couple joined Beth Meyer soon after arriving in Raleigh in 2007.

After the Tree of Life shooting in Pittsburgh in 2018 — one year before his daughter’s bat mitzvah — Barbieri realized the attack could have happened at any synagogue anywhere in the country.

“I wanted to take action to protect my family and the Jewish community that my wife values so much,” he said.

This Yom Kippur, the synagogue wanted to recognize Barbieri for his service on the security team by offering him the honor of carrying the Torah during services. But a few days ago, he came down with COVID and declined. The family will come together after services outdoors to celebrate the breaking of the Yom Kippur fast.