REYKJAVIK, Iceland (RNS) — With the 2011 movie “Thor,” the Avengers film franchise made Thor, Loki and Odin the equals of Iron Man and Black Panther, transforming these ancient Norse gods into mythic Marvel superheroes.

But followers of Ásatrú, or Norse paganism, still honor their gods, and in Iceland, where Ásatrú is the second-most-practiced religion after Christianity, a new temple to the Norse deities is rising now on Öskjuhlíð, a hill overlooking the center of the capital city of Reykjavik. Dedicated to the whole pantheon of Norse gods and nature spirits, it is the first pagan temple to be built in more than 1,000 years.

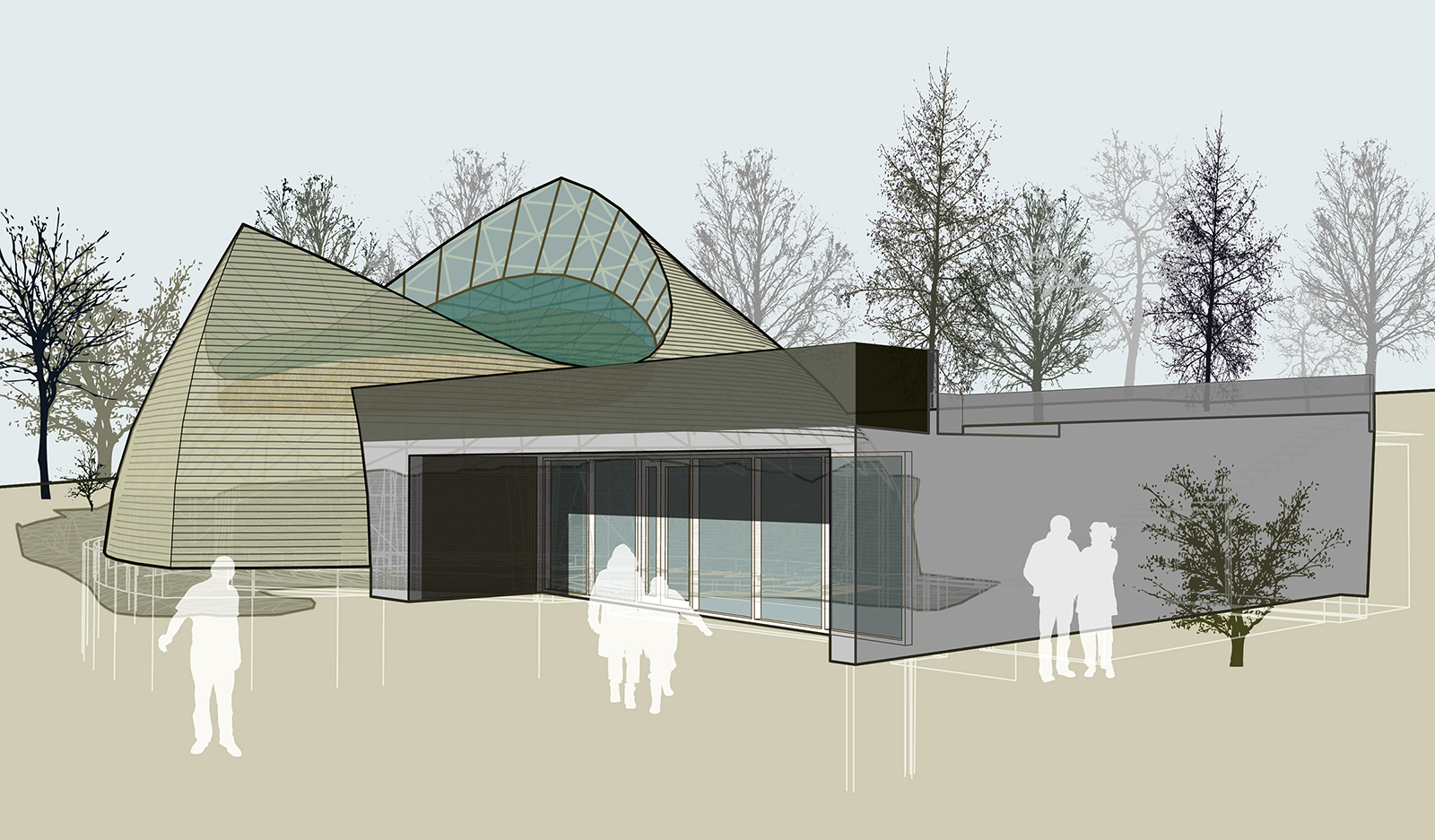

The opening of the temple, or hof in Icelandic, was initially planned for 2016, but the 2008 financial crash, which hit Iceland hard, delayed construction, and progress was further inhibited by the COVID-19 pandemic. Magnús Jensson, the architect of the Hof Ásatrúarfélagsins (“the Temple of the Ásatrú Fellowship”) and a member of the pagan community, said that the plan now is to open the temple in stages over the next few years.

The mostly concrete structure of the 800-square-meter (8,600-square-foot) hof is already largely completed. Meant to evoke the journey into the Norse underworld, the temple is designed as a circle dug into the hill. Apertures in its domed roof, made of an open steel structure, will allow sunlight to illuminate the open hall below, where weddings, naming ceremonies and funerals will be held.

The first area to open will be the sanctum, or sacred space, which, along with space for “social facilities,” makes up about half of the building. Some of these facilities are ready, but the dome over the sanctum itself is still being built. The second phase, expected to be completed in 2026, will include more social facilities, a library, cafe and feast halls.

An artistic rendering of the Hof Ásatrúarfélagsins, or Temple of the Asatru Fellowship, in Reykjavik, Iceland, designed by Magnús Jensson. (Image courtesy of Magnús Jensson)

The entire temple will be opened when Iceland’s population reaches 432,000 people, an auspicious number, according to Hilmar Örn Hilmarsson, 65, the allsherjargoði, or high priest, of the Ásatrú Fellowship.

Ásatrú was brought to Iceland by the Vikings from Scandinavia in 874 A.D. but declined after King Olaf Tryggvason chose Christianity as the state religion around 1000.

The faith made a resurgence in the 1970s under the leadership of Sveinbjörn Beinteinsson, a sheep farmer and poet. It first gained recognition by the government in 1973 and today is believed to be growing rapidly. The faith has about 7,000 active members in a population of 387,000.

For the past two decades, the community has been led by Hilmarsson. There are 11 other priests currently residing in Iceland, both male and female, and two new ones will be ordained this year.

Ásatrú celebrates the seasons, with the biggest observances being the summer Blót in April and winter Blót in October. As for doctrine, “there is no revealed truth or strict commandments, only ‘polite recommendations,’” Hilmarsson explained.

Followers do believe that nature spirits inhabit certain places. “We are very similar to Hinduism in that way and view them as a ‘sister religion,’” he said.

A group from Slovenia tours part of Hof Ásatrúarfélagsins, or Temple of the Asatru Fellowship, in Reykjavik, Iceland, in late September 2023. (Photo courtesy of Hof Ásatrúarfélagsins)

But he said that Ásatrú suffers from outsiders’ misunderstandings, many of them stemming from their portrayals in books and movies. As with Marvel’s depictions of Ásatrú gods, the elves and trolls that populate the religion’s stories are very different from “how Tolkien portrayed them.”

He also said that when people ask about the Viking gods they are familiar with from popular culture, he responds that the depictions in fiction are not true to the original folk tales although “it might be entertaining and interesting to see them on screen.”

Nor do the Norse worship inanimate idols, Hilmarsson said, even though figures of sacred beings are frequently displayed. “Statues are not important,” he explained. “Rather, many of the stories need to be visualized.”

The most damaging misconception is that followers of Ásatrú subscribe to racist ideas about European superiority. Owing to Iceland’s relatively new history of immigration, the community has very few nonwhite adherents. Hilmarsson said his community strictly distances itself from neopagan groups that espouse white supremacist beliefs.

“We are open to all, just like it was in the old days,” he said. “When the original religion was practiced, they didn’t have the modern concept of ‘race.’ Also, ancient people used to allow marriage between clans and cultures, to build alliances and make peace. This was one blueprint of their society.”

Ásatrú priests have performed weddings for same-sex couples since 2003, years before Iceland officially recognized the practice in 2010.

Aerial view of Reykjavik, Iceland. (Photo by Einar H. Reynis/Unsplash/Creative Commons)

After 1,000 years, there is an irony in the idea that reviving an ancient Icelandic religion could contribute to the island nation’s diversity. However, Jensson, the hof’s architect, adds that their difference will contribute to global religious diversity in general.

“We are very excited that we now have a temple after so long,” he said.

Jensson added that the temple will allow Icelanders to explore their past. “Most of Iceland’s history was written by Christians and we were simply told that the people were ‘just fine’ with leaving behind all the traditions and knowledge of their ancestors.”