NEW DELHI, India (RNS) — On a roundabout at a lively intersection of Sunehri Bagh Road, at the heart of India’s capital, the landmark Sunehri mosque has stood for at least 150 years. For the last two decades and more, Abdul Aziz has delivered sermons and led prayer at the mosque, its walls echoing with the same prayers his grandfather once said when he was imam.

These days, in his five daily prayers, Aziz asks for the protection of the mosque. In June, the New Delhi Municipal Corp. deemed it a traffic hazard and slated it for demolition.

Despite his deep ties to the mosque, Aziz, 46, first heard about its fate from an announcement in a newspaper. The city’s decision brought public outrage, as the mosque, renowned for its magnificent architecture, had also long been a symbol of India’s ethos of pluralism and peaceful coexistence. The reason given for the plan, additionally, struck many as bizarre. NDMC received over 6,000 emails from numerous heritage conservationists and Muslim organizations expressing opposition to the demolition.

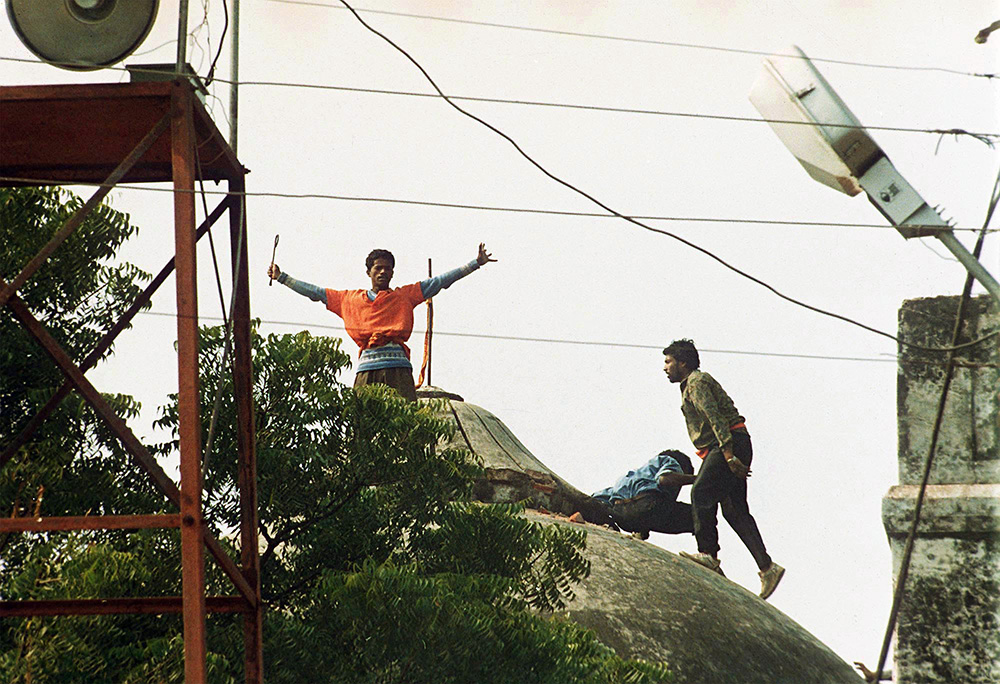

For decades Hindu nationalist organizations such as the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh, known as RSS, have sought to remove or alter historical Muslim sites, particularly mosques. The most famous example was the disputed 16th century Babri Mosque in Ayodhya, in northeastern India. After years of wrangling over whether it was erected over an even more ancient Hindu shrine, the Babri Masjid was torn down by a right-wing Hindu mob in 1992. In the riots that followed, at least 2,000 people, mostly Muslims, lost their lives. In January, after decades more controversy, a lavish new Hindu temple to the god Ram opened on the spot.

Hindu fundamentalists stand on top of one of the three domes of the Babri mosque in Ayodhya, India, on Dec. 6, 1992, after storming the secured site. Thousands of Hindu extremists razed the 430-year-old Muslim mosque in 1992 to clear a site for a proposed Hindu temple. (AP Photo/Udo Weitz)

Since 2014, when the Bharatiya Janata Party, led by Prime Minister Narendra Modi, came to power, RSS, once banned for inciting violence, and the Vishwa Hindu Parishad have stepped up their campaign against mosques.

When these groups target a mosque, they normally make a case over years for its destruction. Last year, a petition was filed to transfer the historic Gyanvapi mosque in Varanasi, the holy city in Uttar Pradesh, to Hindu owners, arguing that a temple predated the mosque. Multiple petitions have been lodged against the Shahi Idgah Mosque in Mathura, southeast of New Delhi, and the Quwwatul Islam Mosque in the capital, all rooted in similar claims.

On Jan. 30, New Delhi authorities razed the 600-year-old Akhoondji Mosque, saying it was an illegal structure. A Islamic school, a cemetery and Sufi shrine were demolished along with the mosque. The Delhi waqf, a commission that administers Muslim sites in the city, said it was not given ample warning before the mosque was torn down.

The campaign against historic mosques parallels the Modi government’s effort to redefine Indian-ness as essentially Hindu, disrupting the country’s long-standing commitment to secularism and threatening to relegate Muslims to second-class citizenship.

Aziz has filed a petition in the Delhi High Court to protect the Sunehri structure. “The rationale citing traffic concerns seems weak, considering there are numerous roundabouts in this area that experience congestion during peak hours,” he told Religion News Service. “If traffic is the issue, there are numerous alternatives to address it without resorting to the demolition of the masjid, as witnessed in many other locations in Delhi.”

The Delhi Waqf Board also took the matter to the High Court last year. The court dismissed the board’s plea on Dec. 18, prompting a coalition of historians and lawyers, including the Indian Civil Liberties Union, to write to the NDMC emphasizing the significance of the mosque and presenting alternative solutions.

Interior of the more than 150-year-old Sunehri Bagh Masjid in Delhi, India. (Photo by Kaisar Andrabi)

Aziz reminisces about his childhood at the mosque, when India’s Prime Minister Indira Gandhi would pass by the mosque escorted by security vehicles. He and his father, who also served as imam, would catch glimpses of her and sometimes get a wave. His father would teach him about the neighborhood’s design, the work of Edwin Lutyens, the principal architect of the British colonial development of New Delhi in the early 20th century.

Among the accomplishments of Lutyens’ design is that he managed to build the new city without altering the structure of the two-story mosque, adorned with a humble Bangla dome and flanked by four minarets and surrounded by a small park.

Advocate Anas Tanwir, the founder of ICLU, told RNS that the mosque’s dome, Lakhori brick masonry, sandstone flooring and vaulted roof are typical of the period. “It’s a sign of our freedom struggle, and its history transcends beyond its walls,” he said.

The British began building New Delhi in 1912 around the ancient city of Raisina, relocating the existing population and razing homes, palaces, tombs and places of worship, built over the centuries. At the time, the government gave the Archaeological Survey of India the task of registering historic buildings, with a view to identifying which should be preserved and which might be demolished.

Among those spared were structures of historical or architectural significance, such as the ancient observatory Jantar Mantar or the tomb of the Mughal emperor Humayun. Several other old places of worship were spared mainly because they were still in use. The Sunehri mosque, of interest for its architecture, is also significant for its location on one of the roundabouts that characterize Lutyens’ city plan.

“The street plan made up of intersecting radial roads and roundabouts was laid on land that was already dotted with historic structures. Not only did the planners of New Delhi make room for these structures, but they took this existing historic landscape as their starting point in a very fundamental way,” historian Swapna Liddle has said.

Syed Irfan Habib, a prominent historian and heritage conservationist in Delhi, said the Sunheri mosque served as a residence for the distinguished freedom fighter and poet of the British era Hasrat Mohani. Mohani is credited and celebrated for coining the term “Inquilab Zindabad,” a phrase that stands as one of the most popular slogans of India’s struggle for freedom from the British.

The secular nation that struggle produced, said Habib, is a birthright of all Indians. “The notion of secularism isn’t solely the concern of Muslims. The idea of a secular, socialist, pluralistic and progressive India is a legacy from our freedom fighters, a conscious decision made in contrast to Pakistan becoming an Islamic nation,” he said.

Besides the loss to history is the loss for those who frequent the mosque as a house of worship. “The new India seems to derive more joy from the demolition of mosques than the construction of new temples,” said Jibran Ahmad, who works nearby and is a regular visitor to the Sunehri mosque. “It’s not just Muslims. Mosques are equally subjected to hate.”