(RNS) — Every Friday, Dr. Sadaf Lodhi releases a new episode of “The Muslim Sex Podcast,” in which she discusses everything from painful sex to how orgasm happens to the effects of purity culture on intimacy. In each hourlong show, Lodhi dispels stigmas attached to sex while giving listeners keys to understanding their bodies better.

Lodhi, an OB/GYN and a sex coach in New York, launched the podcast three years ago to make sex education more accessible for all, but in particular for Pakistani American Muslims like her. At the start of every episode, she warns, “It is called ‘The Muslim Sex Podcast’ because I happen to be a Muslim woman who talks about sex.”

But the title also tips listeners that the podcast means to change minds about Islam and sex. There is a widespread assumption that Islam is a puritanical faith, a notion that Muslim sex educators like Lodhi are trying to combat. The misapprehension, they say, comes from the fact that in many Muslim countries there has been little separation between faith and other social fixtures, such as government or culture.

“The culture and religion become so intermixed that it’s hard to parse through what is what,” said Lodhi.

As a result, when it comes to sexual health, Muslim women are often underserved and subject to sexual dysfunction. A 2023 survey for The Journal of Sexual Medicine of adult Muslim cisgender women in the U.S. and Canada showed that 42% reported having a history of sexual pain, and 65% of them never sought help from a health care provider.

Dr. Sadaf Lodhi. (Courtesy photo)

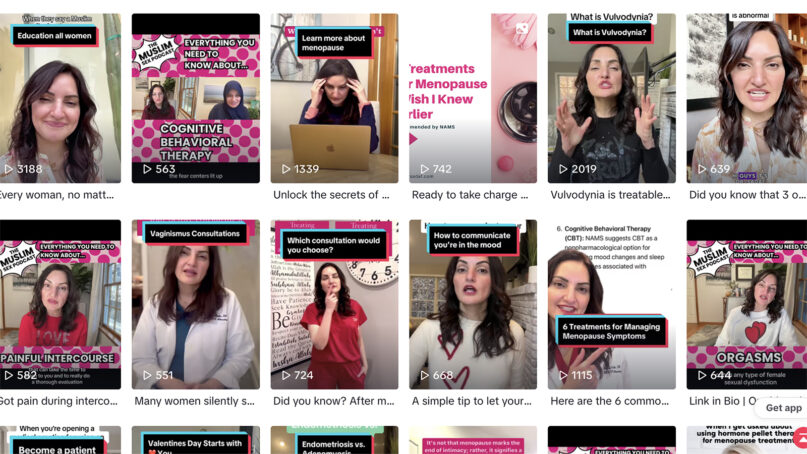

To mitigate the damage negative messages have on adults’ sex lives, Lodhi has reached out to a younger audience on TikTok, where she shares her advice with her 116,000 followers. Too often, she said, sex education for teens focuses on the risks, such as sexually transmitted infections or unwanted pregnancies. “All of these things are very important, don’t get me wrong,” said Lodhi. “But what we don’t focus on is consent, on intimate partner violence, on pleasure. And those are things that your kids don’t have access to.”

Angelica Lindsey-Ali, a health professional, sees her sex coaching work as a way of spreading Islam’s sex-positive teachings to help empower Muslim women. “A lot of women were misunderstanding what Islam actually says about sexual health and reproductive health. That’s why I started my work,” she said.

In 1998, after converting to Islam at the age of 23, Lindsey-Ali was the victim of a sexual assault. As she looked for answers on what Islam says about sex, sexual assault and consent, she realized few women knew about it and wanted to educate them on the topic.

Lindsey-Ali, who lives in Phoenix, drew on her background as a specialist in HIV, STIs and hepatitis C treatment with her knowledge of Black communities to cater specifically to, but not exclusively for, Black Muslim women like her.

On social media, she is known as “the Village Auntie.” In African culture, an auntie is a familiar figure who works as a healer, marriage counselor and midwife, and Lindsey-Ali seeks to embody a 21st-century version, re-creating “the wise woman of the village” for her followers. “I wanted to reclaim that role in a modern society using social media and the digital landscape because we’re so disconnected from each other,” she said.

Angelica Lindsey-Ali. (Courtesy photo)

Lindsey-Ali, who majored in African studies in college and is married to a man from Ghana, is intent on raising awareness about female genital mutilation, a traditional practice that is common in some African countries, in which parts of girls’ external genitalia are removed.

Many argue that FGM is a religious requirement, though there is no ground for the claim. According to the World Health Organization, an estimated 200 million women alive today have undergone FGM.

When helping women who have undergone FGM, Lindsey-Ali said, she gently presents evidence that shows that Islam prohibits the operation.

She too combats the sexual conservatism of many Islamic cultures, while addressing the hypersexualization Black women endure. She tries, she said, to “root out the spaces where the conservatism sort of leads to misinformation, while also shielding them from this idea that we’re just hypersexual.”

An important part of her job, said Lindsey-Ali, is building trust with her audience, always backing her claims with religious sources and employing stories from the Quran when needed. When women struggling with menopause symptoms open up about how it affects their confidence and their self-image, Lindsey-Ali draws on stories of women like Khadijah, who married the Prophet Muhammad at 40 years old.

“A lot of the women throughout Islamic history were not necessarily young women. What does that say about the continued vitality and desirability of women who are at that age? So I really push back against that ageism in an affirming way through the use of stories,” she said.

Lindsey-Ali said her work initially drew criticism from many in the Muslim community who thought she was challenging Islam’s teachings on premarital sex. But today, religious leaders acknowledge the need for sex education, and imams and sheiks often invite Lindsey-Ali to mosques to talk with women, particularly in Black Muslim communities.

Nadiah Mohajir. (Photo by Wajiha Ibrahim, courtesy of Heart)

Equipping Muslim communities to lead their own discussions is the goal of Heart to Grow, a Chicago-based organization that has worked for a decade to provide Muslim communities with tools to fight sexual violence, training imams, chaplains and principals of Islamic schools, as well as non-Muslim health providers and other professionals who encounter Muslim sexual assault survivors.

“We equip them with the information and skills that they might need to be able to not only answer questions or be a source of support but also do it in a culturally competent way. That is, it allows people to feel like they are in control and not being talked down to or told how to do something,” said Nadiah Mohajir, CEO and co-founder of Heart.

Mohajir created Heart after organizing an outreach campaign for Muslim women and their daughters for the Department of Health and Human Services’ Office of Women’s Health, under the Obama administration. A mother-daughter day where participants discussed sexual violence, reproductive health and relationships inspired her to pursue the work further.

In 2022, Heart published “The Sex Talk: A Muslim’s Guide to Healthy Sex and Relationships,” a textbook with information about anatomy, sexual diseases and contraception options that comes with a workbook inviting readers to reflect on consent and boundaries in relationships. The book also discusses where Islam fits in all of these discussions.

Because there are various traditions and scholars’ movements within Islam, Mohajir always encourages people to consult different sources when trying to understand what Islam says about abortion or birth control.

“Often, people just feel stuck. Then, they make uninformed decisions or stay in unhealthy relationships or situations because they think that’s the only right way to do things. The beauty of our faith is that there are multiple ways to think about it,” she said.

But one Islamic principle at the center of all her work can always serve as a guide: Rahma, or compassion in Arabic. ”Muslims are encouraged to meet each other first and foremost with compassion, no matter what we’re talking about. Right, just give each other grace, give each other Rahma.”

This article was updated to correct in paragraph 7 that Angelica Lindsey-Ali isn’t a former health professional but still works in the field and isn’t a social media influencer.