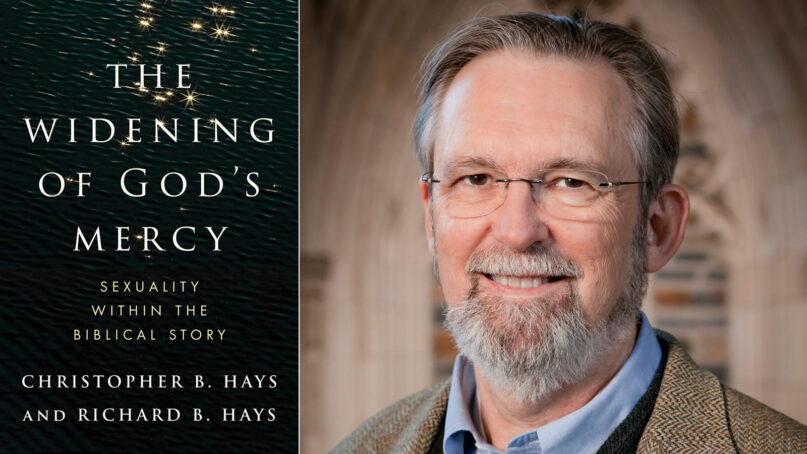

(RNS) — This month, Yale University Press released “The Widening of God’s Mercy: Sexuality Within the Biblical Story,” a highly anticipated book coauthored by preeminent New Testament scholar Richard Hays and his son, Christopher, himself a respected Old Testament scholar, in which they seek to make a biblical case for same-sex relationships and marriage.

“We advocate for full inclusion of believers with differing sexual orientations not because we reject the authority of the Bible,” the pair write. “Far from it: We have come to advocate their inclusion precisely because we affirm the force and authority of the Bible’s ongoing story of God’s mercy.”

Two respected Christian thinkers making a biblical argument for LGBTQ+ relationships and inclusion would have been newsworthy just a decade or two ago; in recent years, many scholars, pastors and lay thinkers have published books drawing similar conclusions. So while the Hayses add their voices to the chorus and strike some new notes, they are a bit late to the concert.

But the most remarkable thing about this book is not its arguments, interesting and important as they are, but rather Richard Hays’ name on its cover.

For the last quarter-century, conservative Christians have been citing Hays to argue against same-sex relationships and marriage. His 1996 book “The Moral Vision of the New Testament” argued that the Bible explicitly prohibits LGBTQ+ marriage. Homosexuality, he wrote, “is one among many tragic signs that we are a broken people, alienated from God’s loving purpose.”

Since news of the current book broke, the conservative Christian love affair with Hays has ended. The Council of Biblical Manhood and Womanhood has lamented Hays’ change of mind as “a cause of grief and sadness.” The Gospel Coalition has declared that the Hayses are “deceiving people when it comes to God’s offer” of salvation, and Albert Mohler of the Southern Baptist Theological Seminary called the book “heresy…. A full doctrinal revolt.”

One might wonder why Hays, 76-years-old and battling pancreatic cancer, would choose to publish a provocative book years after retiring from Duke Divinity School. Hays’ answer is simple: This book is an effort to engage in an ancient Christian practice that he has taught about in classrooms for years: repentance.

In a video interview, Hays described the book to me as a metanoia, an ancient Greek word meaning “change of mind” and translated as “repentance” in English versions of the New Testament, where it appears 20 times; the verb “repent” appears an additional 27 times. A recurrent theme in the teachings of Jesus, it’s also a fixture in the prophetic cries of John the Baptizer and a main message of the Apostle Paul, who taught that living according to God’s will means to be “transformed by the renewing of your mind.”

Hays says metanoia denotes more than feeling or saying you are sorry; it means taking action to demonstrate one’s new perspective. “The Widening of God’s Mercy” is his effort to do just that.

“The present book is, for me, an effort to offer contrition and to set the record straight on where I now stand … I am deeply sorry. The present book can’t undo past damage, but I pray that it may be of some help,” Hays told me.

Those harmed by Hays’ previous work may reply that even the most magisterial volume of repentance won’t undo the damage caused by his previous work. It’s impossible to repay the generation that has been psychologically tortured by conservative pastors and parents armed with Hays’ “moral vision” for their lives. However impactful his new book, Hays can’t make up for the years of sanity lost to depression, the sense of rejection by one’s creator, countless prayers pleading to be changed that went unanswered. No book can pay such a debt.

At the same time, repentance requires us to attempt to seek forgiveness and make repair, no matter how delayed. It takes uncommon courage to make amends for past mistakes in the twilight of one’s life, and it’s a step that Hays frankly did not have to take. It has already cost him the respect and accolades of an influential swath of Christianity.

If Christians are nothing else, they are people who know how to change their minds. Today, however, some types of Christians have come to regard changing one’s mind as a sign of spiritual weakness, as if it can only be the fruit of cultural capitulation or compromise. I’ve heard pastors and theologians like Mohler brag about believing exactly the same things today as they did when they were mere youths.

They may be models of consistency, but they seem to know very little about the practice of repentance beyond the moment of Christian conversion. By definition, consistency and repentance are forces at odds. To repent is literally to forfeit one’s consistency.

The late Christian writer Frederick Buechner said, “To repent is to come to your senses.” And, Buechner added, it’s not so much something you do as it is something that happens to you. For Hays, at least, this is how it began.

Hays goes directly at his critics on this point. In the years after the publication of “A Moral Vision of the New Testament,” Hays said in our interview, he began to feel “deeply troubled by the way my chapter has been appropriated as ammunition by some individuals and groups taking the uncompromising ‘conservative’ position.”

When he penned his book in 1996, he said, he considered the chapter on homosexuality to be “proposals about how to best discern the New Testament’s relevance for difficult and contested questions in our time” that could “start a conversation rather than end one.” As conservatives seized upon his words and used them “as a cover for exclusionary attitudes and practices wrapped in more ‘compassionate’ packaging,” Hays realized he had been naïve.

Hays’ thinking was also challenged by the spiritual fidelity of the gay and lesbian people in his life. He describes his church as “a grace-filled church community where gay and lesbian Christians participate fully as members and as leaders, without making it into a church-defining issue.” The more he considered the many LGBTQ+ students in his classroom who were “both excellent students and gracious, compassionate people,” the harder it became “to say that they should have the door slammed on them in terms of admittance to the full range of the church’s sacraments.”

If these sexual minorities existed outside of God’s good graces, then why was Hays witnessing so much undeniable spiritual fruit in their lives?

It all came to a head at the outset of the COVID-19 pandemic. Hays had watched with dismay as Christopher’s employer, Fuller Theological Seminary, began expelling homosexuals and allies from their community.

“I was not proud of what had happened at this school where I worked,” Christopher told me. “And I had a hunch, too, that my Dad didn’t feel comfortable with what had come of what he’d written, and that his heart was in a different place, too, but we had never really talked it out.”

Father and son entered into a period of intentional conversations as the pandemic went along, and they wrote out what they had come to believe. The result was a picture of a God who changes his mind in response to human pain and seeking, and who is always expanding the reach of his mercy.

Through this process Richard Hays realized that in his previous work, he had been “more concerned about my own intellectual project than about the pain of gay and lesbian people inside and outside the church, including those driven out of the church by unloving condemnation.”

He decided, along with Christopher, to write a book arguing for full inclusion of LGBTQ+ people into the life of faith that includes an epilogue written by Richard in which he profusely apologizes for the harm his previous work has caused.

“The Widening of God’s Mercy” is a prestigious New Testament scholar’s attempt to demonstrate that he has come to his senses. What remains to be seen, but will soon become apparent, is whether those Christians who are still unconvinced about the faithfulness of sexual minorities will join him.