(RNS) — On a Saturday morning in 2009, Amanda Tyler was in a grocery store parking lot in Austin, Texas, setting up for Democratic Congressman Lloyd Doggett’s “neighborhood office hours,” when a large crowd of conservative protesters swarmed the congressman and his staff, waving “Don’t Tread on Me” flags and holding signs with Rep. Doggett’s face, drawn with devil horns, printed on tombstones and written with messages like “No Socialized Healthcare.”

Tyler, who was Doggett’s district director at the time, recalls this moment as the most intimidating of her career. The same protesters, she said, stalked the congressman for months afterward, attending different events, brandishing assault rifles and shouting about evil.

“It gave me a very close-up experience with the political tactics that could be used and how violent they could be,” Tyler said. “They had distorted the congressman’s face to look like a demon — so dehumanizing — and used symbols that felt like spiritual warfare.”

The event in Texas was a turning point for Tyler, who would a decade later launch the initiative “Christians Against Christian Nationalism” in 2019, and in 2021, become the executive director of the Baptist Joint Committee for Religious Liberty, where she advocates for religious liberty and the separation of church and state.

The chaos and hostility of that Saturday morning in Texas, Tyler says, served as a prelude to the political intimidation tactics seen on Jan. 6, 2021.

“Christian nationalism was not the sole cause of explanation for the events of January 6, but it played a vital role in the events leading up to the siege and provided a unifying ideology for many disparate groups that day,” Tyler writes in her debut book.

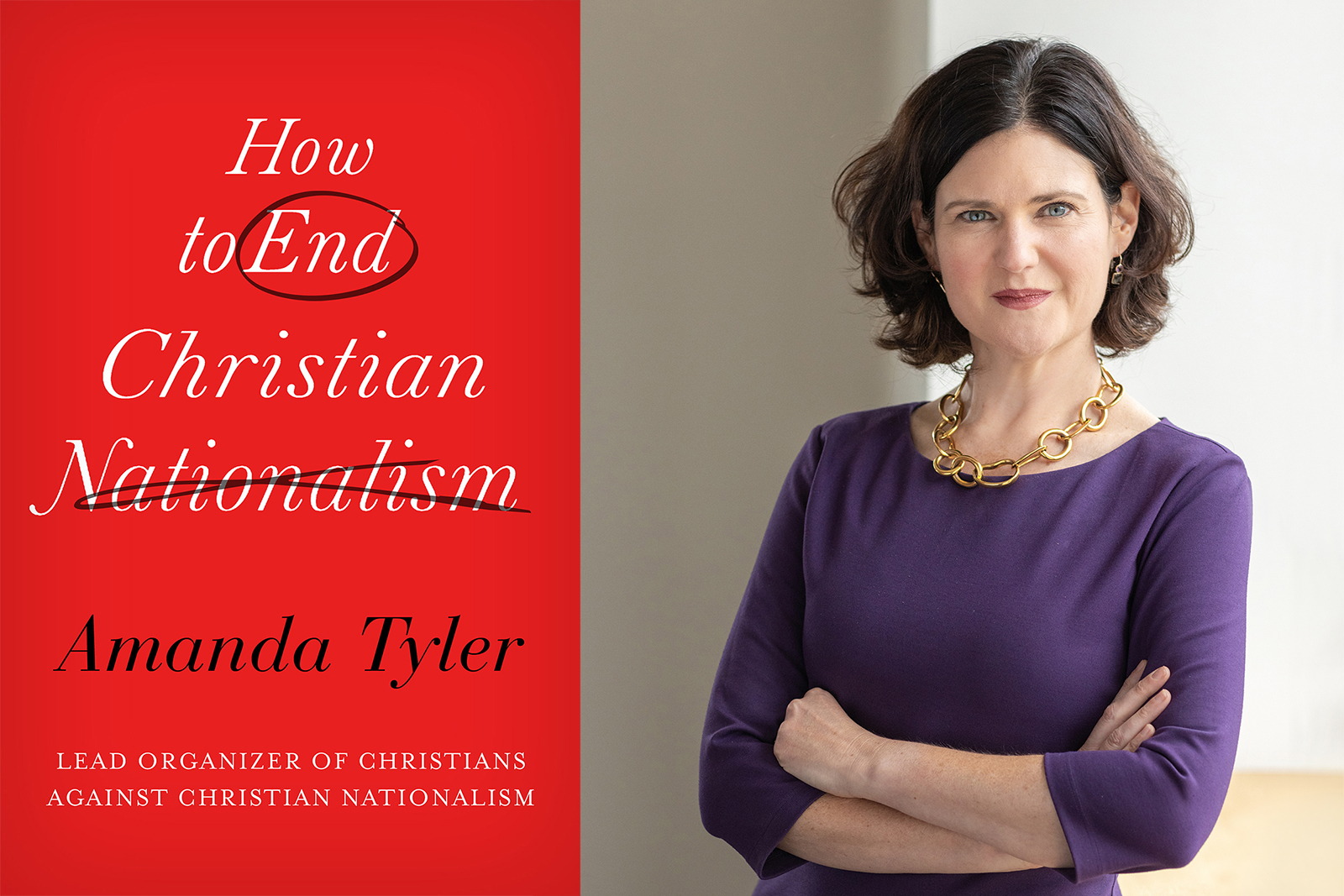

“How to End Christian Nationalism,” published Oct. 22, presents itself as a roadmap to building multiracial interfaith coalitions and fostering what Tyler calls “uncomfortable” but necessary conversations — especially for white Christians. The task of dismantling Christian nationalism, Tyler warns, is generational work.

“It is up to us to confront and call out the destructive ideology that it is and … the damage that it is causing our country.”

In her view, Christian nationalism is not just a theological distortion but a dangerous ideology with real-world consequences. It’s a movement, she argues, that undermines the core principles of both Christianity and democracy. According to Tyler, the ideology promotes the idea that America was founded as a Christian nation, and to be an authentic American, one must subscribe to a conservative, often Protestant, expression of Christianity. She argues that Christian nationalism distorts the gospel of Jesus, which represents to her a message of lovingkindness “beyond recognition.”

“Jesus eschewed political power in favor of a ministry aligned with those who were oppressed, marginalized, and otherwise harmed by that power,” Tyler writes. “It (Christian nationalism) points not to Jesus of Nazareth but to the nation, as conceived by a dangerous political ideology, as the object of allegiance.”

Her experiences as a lawyer and activist in Texas and Washington, D.C., buttress an argument that links Christian nationalism to the violent events of Jan. 6, white supremacy and xenophobia. Her religious background, a Baptist from Austin, lends an urgency to the stakes at play.

“It is not a memoir, but there is a lot of my personal story in it,” Tyler told RNS.

As Tyler describes it, her journey to end Christian nationalism began 40 years ago when she “made my profession of faith in the baptismal waters at Riverbend Baptist Church in Austin, Texas,” she writes.

“This is just who I am,” Tyler said. “Learning about Jesus, trying to become a better Christian … This work trying to end Christian nationalism now as a lifelong calling. I didn’t know that at the time, I was only 7, but that started me on this path.”

While her faith was developing, so were her political aspirations. At 6, Tyler recalls studying local city council candidates and pestering her politically inactive parents about who they would vote for. “I was a bit of an outlier, even in my own family,” she said. After hearing a Texas state senator speak at career day, she knew she was destined to become a lawyer.

“I raised my hand and asked him, how does one become a senator?” Tyler said. “He suggested that I go to law school.”

Tyler’s book takes a systematic approach, organized into eight sections titled “Step One” through “Step Eight.” Many end with a reading and reflection exercise that incorporates biblical Scripture. “I pray that it is a hopeful resource for people in growing the movement against Christian nationalism,” Tyler said.

In “Step One,” she introduces a sociological survey designed to help readers orient themselves to Christian nationalism. Some of the questions read, “The federal government should advocate Christian values” and “The success of the United States is part of God’s plan.”

“I hope people see that this is not something that impacts a select part of the population,” Tyler said. “It’s something we all have a stake in.”

Christian nationalism is an ideology that exerts its influence along a spectrum, according to Tyler. She notes instances in American history: from the Naturalization Act of 1790, which was the first law in the United States outlining rules for granting citizenship, to the rapid growth of the Ku Klux Klan to the Red Scare of the 1950s when “In God We Trust” became a national motto.

In essence, Tyler argues that Christian nationalism relates to white supremacy in its promotion of exclusionary visions of power — one through race, the other through religion — and how they often overlap in rhetoric, goals and supporters.

“Since Christian nationalism perpetuates both white supremacy and Christian supremacy,” Tyler writes, “white Christians are still at the top of the caste system created in part by Christian nationalism.”

Tyler’s advocacy is rooted in personal experience and spiritual conviction — but she is not interested in doing this work alone. In January of 2023, she launched the podcast “Respecting Religion” with co-host Holly Hollman. They often discuss the intersection of faith, politics and social justice with guests like Jemar Tisby, the Rev. Jay Augustine and the Rev. Joseph Evans. Tyler emphasizes the need to center people of color in the work of dismantling Christian nationalism.

“There’s a tendency sometimes for white people to think that we have to run and invent everything,” Tyler said. “But there are already groups who are doing this work — whether or not they’ve called it Christian nationalism.”

Frequently addressing her readers using “we,” Tyler suggests that her readers are likely white, Christian and concerned. She avoids labeling individuals as Christian nationalists. Like a few studies she cites, Tyler says she wants to focus on the dynamics of the ideology rather than assigning the label to a group of people.

It isn’t difficult, however, for readers to imagine the contemporary Christian nationalist Tyler neglects to describe: Images of those who stormed the capitol on Jan. 6 were rife with Christian flags and Bible verses. However, in her book, Tyler is clear the messaging has reached far more than the most extreme ends of the spectrum. She warns that many of “our friends, relatives and colleagues” may be “falling prey” to Christian nationalist messaging.

“They need people in their lives — people like you and me,” Tyler writes, “who can help them understand Christian nationalism well enough to reject it.”

This article was produced as part of the RNS/Interfaith America Religion Journalism Fellowship.