(RNS) — Hanukkah is here, and with it, the annual need to retell the story, and to make sure that we all know why, exactly, we are celebrating this holiday.

No, this holiday was not about that little bit of oil, sufficient for one night’s lighting, that lasted for eight nights. That is a story from the Talmud, about five centuries after the Maccabees.

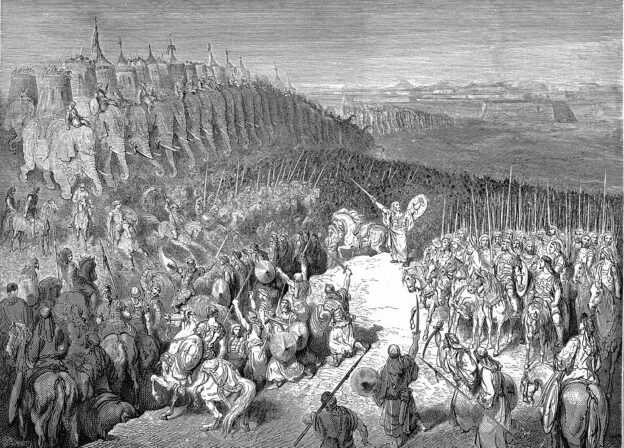

The oil wasn’t the miracle of Hanukkah. The real miracle was that the Maccabees, a tiny band of Jewish guerrillas, defeated the Syrian-Greek army — the mightiest army in the world — and reestablished Jewish sovereignty in Judea. History has regarded Judah Maccabee as one of the most brilliant military strategists of all time; for that reason, there is a statue of him at West Point.

Or perhaps there was a larger miracle — even more significant than the military victory. It is not only that the Judeans were fighting the most powerful army of the time. They were also fighting the most sophisticated and powerful culture of its time — Hellenism — and its many incursions into Jewish life. Even more impressive is that the Maccabees were not only victorious over the Syrian-Greeks, but also over those Jews who imbibed Hellenism itself.

“Like country people who come to the big city and are horrified by its fleshpots and sinfulness,” he wrote in “The Jewish Way: Living the Holidays,” so the farmers of Judea were outraged and offended by the nakedness, the “bohemian,” avant-garde air of Hellenism.

This was an internal Jewish civil war, a culture war and a class war — similar to what America is enduring today.

The modern sociological term is “assimilation,” and that accurately describes those ancient Judeans who imitated Greek ways. Some of them endured the oldest form of cosmetic surgery — a procedure to undo the effects of ritual circumcision, so that they could compete, naked, in the Greek gymnasia. To this day, the sophisticated Jewish term for “assimilation” is l’hityaven — “to become Greek.”

Or as some people would put it: They were “self-hating Jews.” For many years, I have heard that term. I confess that I do not like it, and I would like to see it retired.

Why?

First, because it is politically motivated. The accusation of self-hatred, along with its first cousin, JINO (Jew in name only), is most often on the lips of right-wing Jews. They accuse left-wing Jews of disloyalty to either Israel, Zionism or Judaism itself. Those who wield that term are not interested in dialogue. They have rejected pluralism. They refuse to believe that support for Israel, or Zionism, or Jewish identity, comes in many different forms. The term “self-hating Jew” is a blunt instrument. It does not help conversation and dialogue; it puts an end to it.

Second, because it is presumptuous. “Self-hating” has always seemed overly and inappropriately psychoanalytical to me. You should have to pay a lot of money to get a diagnosis like that. I recall the “Curb Your Enthusiasm” episode in which Larry David’s neighbor accuses him of being a self-hating Jew because he was whistling a tune by Richard Wagner. “I do hate myself,” Larry replied, “but it has nothing to do with being Jewish.”

Third, because Jewish self-hatred is real. (My friend, Sander Gilman, wrote an indispensable book on the history of the phenomenon.) The classic example was the Austrian Jewish philosopher Otto Weininger (1880-1903). “He was obsessed with Jews as rootless chameleons,” as Robert Wistrich put it, “divorced from any idea of chivalry, heroism, or virility … ” That’s pretty pathological, if you ask me.

Some Jews really were self-hating: for example, some of the major characters of communism — Karl Marx, Leon Trotsky and Rosa Luxemburg. There have been Nazi sympathizers and white nationalists who were Jewish. For years, I have been haunted by the story of Daniel Burros, a young Jew who hid his identity, rose to the leadership of the Ku Klux Klan and died by suicide after a New York Times reporter exposed his identity.

His story was adapted for the film “The Believer,” which starred Ryan Gosling.

Even Zionism might have been a form of internalized self-hatred. Decades ago, the biblical scholar Yehezkel Kaufmann argued that political Zionism was a conscious rebellion against the image of the defenseless Jew, or the Jew who seemed allergic to physical labor, or the Eastern European Jew who was passive and only interested in study.

Let me return to the assimilated Jews of Hellenistic times, and those who fought against them.

In some ways, the battle was a stalemate. Judaism rejected the Hellenistic worship of the body, as well as its worship of many gods.

But Judaism also opened its doors to some aspects of Hellenistic culture. Jews adopted Hellenistic literary styles. Jews adopted Greek ideas about interpreting texts. The Hebrew language “welcomed” various Greek terms. Judaism welcomed Greek philosophy — both Plato and Aristotle.

Assimilation, as Gerson Cohen taught, was not always a curse. Sometimes, it has been a blessing. Judaism has always been open to what the world is learning and saying. It has fallen to every generation of Jews to determine how much openness is necessary, and how much is too much.

But this thing about accusing the Jew who disagrees with you of being a self-hating Jew — it is no longer helpful, or necessary.

We can do better. We can argue much, much better.