(RNS) — Traditional religion may be destined for the walls of the Cracker Barrel, a space filled with nostalgic advertisements for products of yesteryear, like Victrolas, lace antimacassars or butter churns. All things, in other words, that have been rendered obsolete by modern life.

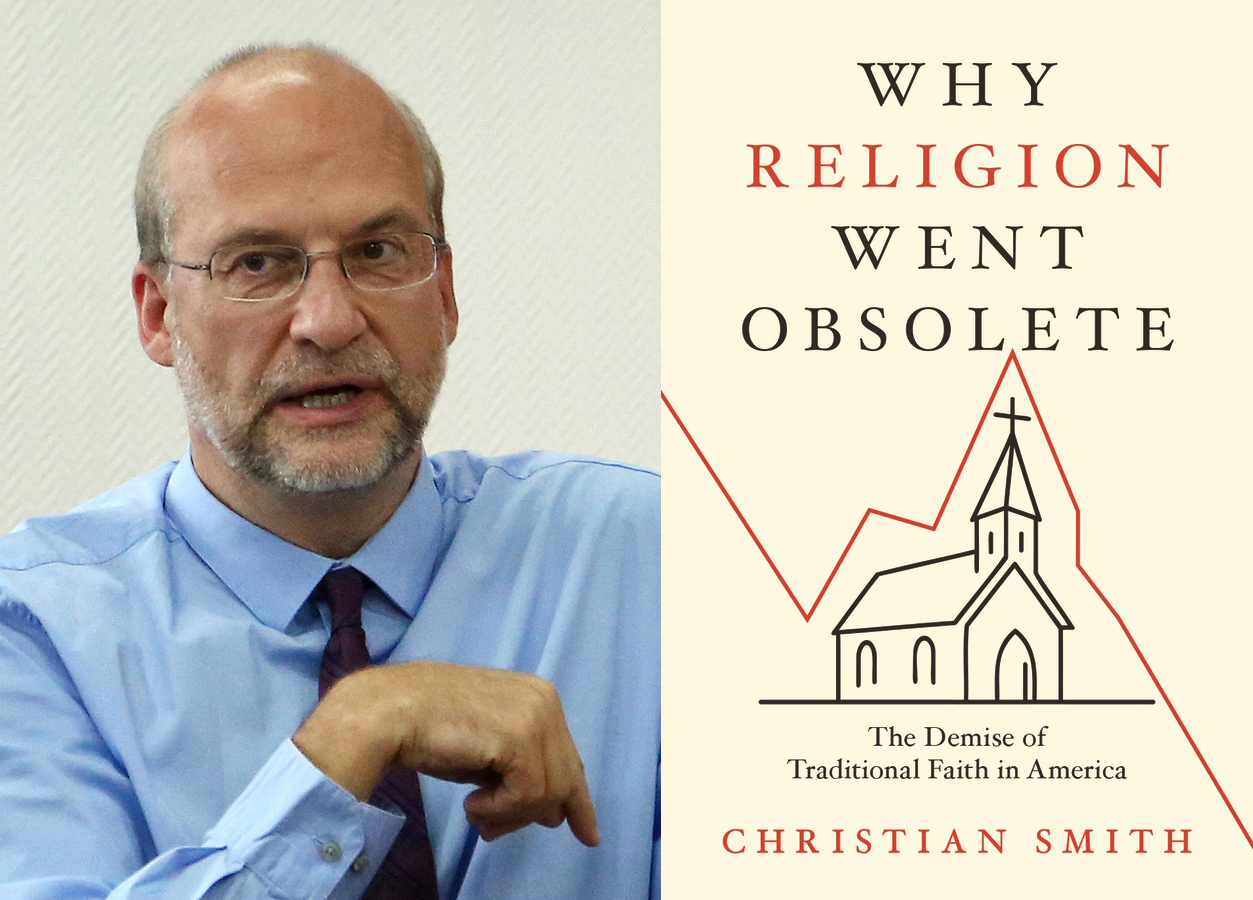

According to social scientist and author Christian Smith, a professor of sociology at the University of Notre Dame, “obsolete” describes the situation facing traditional organized religion in the United States. The title of his new book even puts its cultural expiration in the past tense: “Why Religion Went Obsolete: The Demise of Traditional Faith in America.”

The book, based on research that includes more than 200 qualitative interviews, will be released by Oxford University Press on Tuesday (April 8).

“We almost always use the word ‘decline’ when we talk about if things aren’t going well for religion,” Smith said in a Zoom interview with RNS. “And decline is a good word. But what it’s descriptive of is organizational matters and individual religiousness. Organizations can have decline in membership or adherence, attendance, financial giving. That’s decline — it’s measurable.”

His book, however, chronicles something bigger and harder to pin down. It’s about all the cultural changes that precipitated those declines and made organized religion so much less relevant in people’s lives.

“The culture was formed by these big institutional, technological, economic, geopolitical, military, etc., changes,” he said. Those changes include the rise of individualism, the association of religion with violence after 9/11, the third sexual revolution and more.

Smith is quick to point out that culturally obsolete things can still be quite useful for some people. He has DVDs and CDs in his house that he’s not planning to get rid of. But most younger people rely entirely on streaming services for their movies and music, making DVDs and CDs obsolete for them.

There’s a lesson there. No, religion hasn’t been supplanted by a spiffy new technology — though Smith’s book does detail 10 ways the internet “corroded” religion, including by reducing people’s attention spans and diminishing their willingness to engage in in-person communities that come with significant time demands. Nor was there an intentional plot to derail religion, with secularists setting out to cut it down.

Instead, the social changes that have made religion obsolete were “long-term, highly complex and unintended,” Smith said. Delayed marriage, reduced childbirth and voluntary childlessness have all chipped away at the cultural power of religion, but eroding religion was never the aim of those social changes. People embraced them because they felt their lives were better because of them.

There have also been geopolitical changes, such as the end of the Cold War and the neoliberal economic policies that made people more devoted to their careers in order to stay competitive. Both indirectly damaged religion. The end of the Cold War, Smith writes, “was a jolt that helped to trigger the cultural avalanche that plowed over religion in the next two decades.” Americans who had been brought up to believe that what made us better than the Soviets was that they were godless communists suddenly lost their certainty that being American meant being Christian.

Another factor was the rise of religious scandals, particularly the Catholic Church’s priest sex abuse crisis and the evangelical world’s multiple scandals with pastors who covered up sexual assault and were accused of embezzlement. Even though only a small minority of clergy was involved in those scandals, they “polluted” the name of religion in the eyes of millions, Smith found in his research. In this way, religion has had a hand in digging its own grave.

Smith called this convergence of factors “a perfect storm.” All these elements and more create a zeitgeist that is, if not hostile to religion, not particularly receptive to it.

“It’s very generational,” he said. “This is especially post-boomers, especially millennials. Within the culture for that generation, religion was just kind of discredited or polluted, or it didn’t add up.”

Some people within traditional religion may see the book as being down on religion. That’s not the case though, Smith said. The sociologist’s nearly two dozen previous books have chronicled the highs and lows of religion in America for many years. His National Study of Youth and Religion project researched the religious and spiritual lives of American teenagers into emerging adulthood. His book “Passing the Plate” explored the state of charitable giving in America and considered what might be possible if Christians donated more of their money to worthy causes. And Smith is himself a Christian. He grew up Presbyterian and converted to Roman Catholicism about 15 years ago.

In sum, he’s not pining to see religion on the walls of the Cracker Barrel.

“I don’t have an anti-religious agenda in my scholarship at all,” he said. “I’m a sociologist, so I’m here to describe the world as best I can — what’s happening and why — without cheering it on or without condemning it.”

Now, his job is to explain that shift as best he can using research. While religious people are sometimes defensive or appalled by his message about religion’s obsolescence, other times they receive the news with relief. Presenting his data to audiences, he’s encountered pastors “who just think they’ve failed, like they did a bad job” if their churches aren’t growing, he said.

“I said, ‘It’s not you. There’s something bigger going on here,'” he said. The pastors found it liberating to realize their church’s decline wasn’t only happening to them, or it wasn’t because of something they’d done or failed to do.

“If people don’t have an understanding of those social contexts, it’s very easy for them to personalize it and oftentimes blame themselves,” Smith said.

Smith won’t make a full-on prediction about where religion is headed next, except that just because traditional religion has become obsolete doesn’t mean secularism has triumphed.

“It’s not a binary between religion and the secular,” he said. It’s not the kind of “zero sum game,” but is more nuanced. Most Americans still believe in God, even in younger generations, he added.

Rather, he sees religion morphing into other channels. Interest in the supernatural remains very high in the U.S., which is the topic of another book he’s working on. And he sees an interesting “re-enchantment” happening outside of religious institutions as people explore neopaganism, healing crystals and the like.

“As people left religion, or grew up in a world in which religion was obsolete, they became attracted to this re-enchanted culture. And there’s lots of different entry doors into it,” he said.