(RNS) — During his life, Pope Francis was known for his care for the poor, the vulnerable and those at the margins of his global flock. In line with this commitment, he was also known for living a simple lifestyle, spurning conventions of papal finery. So, it was no surprise that for his funeral, Francis simplified traditions.

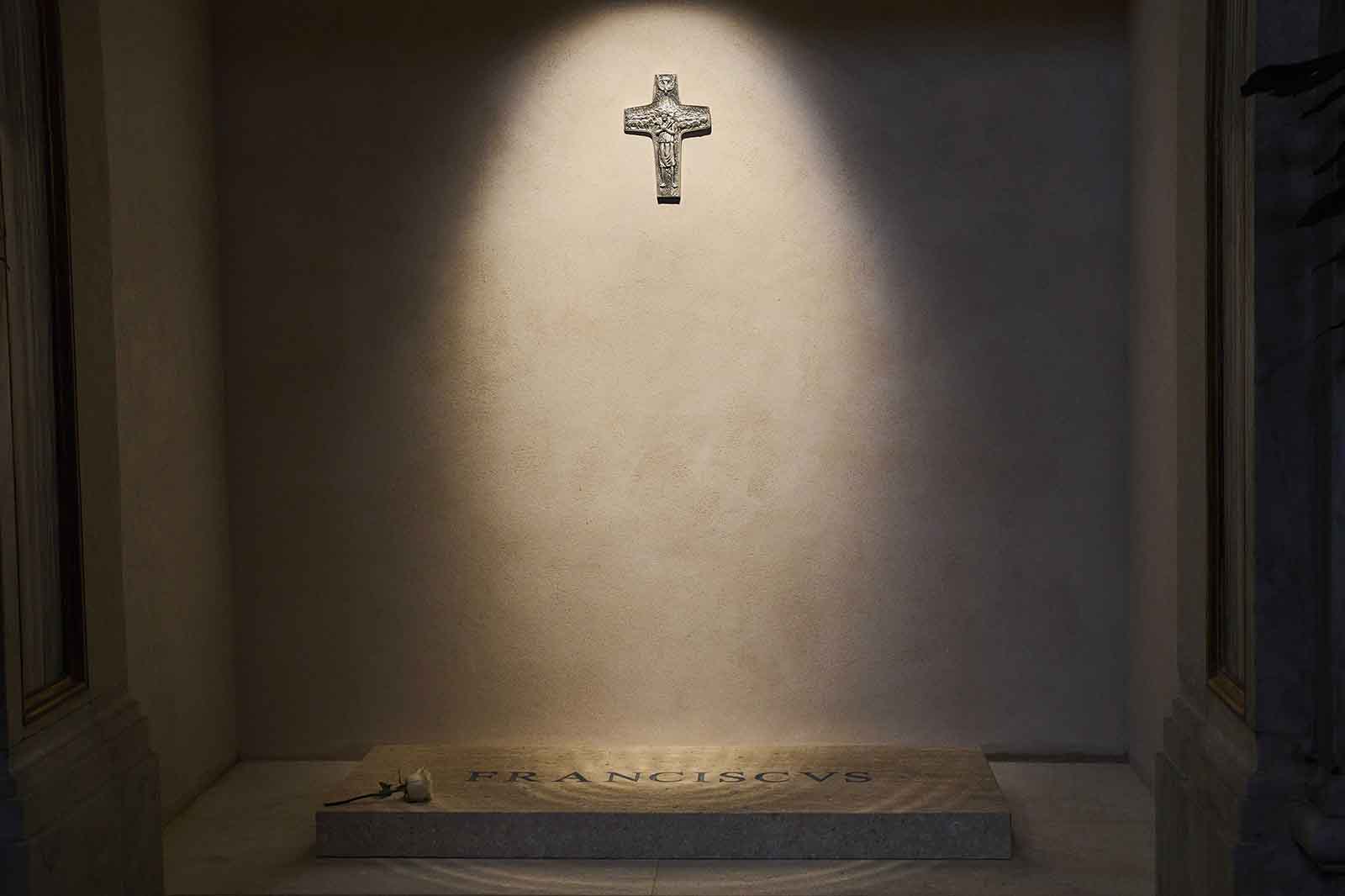

Instead of being buried in a triple coffin as is traditional for popes, Francis opted for a single wood coffin. Rather than being placed on a raised bier during the viewing in St. Peter’s Basilica, Francis lay on a low pedestal, at the same level as those who came to pay their final respects. He also requested he be buried in Santa Maria Maggiore rather than St. Peter’s, laid to rest in a simple tomb “in the earth,” with just the one-word inscription: “Franciscus.”

Francis’ choice for his burial was in keeping with other symbolic choices he made throughout his papacy that reflected his commitment to the poor. He chose to live in simple rooms rather than the traditional papal apartment. He took the name of St. Francis of Assisi, who famously renounced luxury to dedicate his life to the poor. In his autobiography, he wrote he wanted to be buried “with dignity, but like any Christian, because the bishop of Rome is a pastor and a disciple, not a powerful man of this world.”

But Francis is not the first religious leader to connect his funeral choices to respecting the poor. The Babylonian Talmud (Moed Katan 27a-b), composed 1,500 years ago, describes how the rabbinic leadership of an earlier generation decided to pare down burial rituals to ensure the dignity of the poor:

At first the wealthy would take the deceased out for burial on a couch, and the poor would take the deceased out on a plain bier made from poles that were strapped together, and the poor were embarrassed. The Sages instituted that everyone should be taken out for burial on a plain bier, due to the honor of the poor.

According to this text, Jewish burials and funerals used to include some rather ornate practices that were inaccessible to the poor. The passage also mentions how the wealthy used to bring food to mourners in baskets of gold and silver, something the poor could not afford. The rich would serve wine at the mourning meal in fancy pure glass goblets, while the poor could only afford colored glass.

As a result, the rabbis ordered all mourning practices be in accordance with what the poor could access so no one would be embarrassed.

The text goes on, telling us how one of most significant and wealthy Jewish leaders of the period, the sage Rabban Gamliel, waived his own dignity by being buried in simple shrouds, setting the precedent that all Jews be buried in such plain garments:

Likewise, at first taking the dead out for burial was more difficult for the relatives than the actual death, because it was customary to bury the dead in expensive shrouds, which the poor could not afford. The problem grew to the point that relatives would sometimes abandon the corpse and run away. This lasted until Rabban Gamliel came and acted with frivolity, meaning that he waived his dignity, by leaving instructions that he be taken out for burial in linen garments. And the people adopted this practice after him and had themselves taken out for burial in linen garments.

And just as the Jews of the Talmud adopted this practice for themselves, today Jews who opt for traditional burial are still buried in plain white linen shrouds. In a popular guidebook for Jewish death and mourning rituals, Rabbi Maurice Lamm explains that the plain shrouds point to the innate equality of all people:

Wealthy or poor, all are equal before G-d, and that which determines their reward is not what they wear, but what they are. … Shrouds have no pockets. They, therefore, can carry no material wealth. Not a man’s possessions but his soul is of importance.

As a Jew reading about Pope Francis’ funeral wishes, the precedent set by Gamliel immediately came to mind. Here are two religious leaders, centuries apart, breaking with traditions around the sacred rituals of burial and mourning to serve as a model for their communities. Rather than draw attention to their own dignity and biography with their funerals, these two leaders redirect the focus of their communities to the vulnerable among them.

There are, of course, several ways to make choices around burial and mourning rituals that take one’s values into account. Those concerned about the environment can choose a variety of methods for their remains to have a greener departure from this planet. Burying a loved one in their best clothes can signify respect and honor for who they were in life. And choosing a simple, pared down burial can be a way to show one’s commitment to the poor, particularly since the cost of modern burials can run over $10,000.

In her recent book, “The Politics of Ritual,” Molly Farneth explains that mourning rituals have moral force. Mourning and burial rituals are “norm-governed responses” to the loss of someone who mattered to the larger community. The question, “Whom shall we mourn, and how?” is one with moral significance.

Pope Francis’ choice to extend the values of his papacy — prioritizing the poor and the vulnerable — to his funeral is not a minor one. It was a chance to demonstrate moral leadership one last time as he was laid to rest forever.

(Ranana Dine is a Ph.D. candidate at the University of Chicago and the incoming director of the Catholic-Jewish studies program and Crown-Ryan chair in Catholic-Jewish studies at Catholic Theological Union. The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily reflect those of RNS.)