(RNS) — In the past, Catholic social teaching was based on papal documents and appeals to the natural law. Scriptural passages would be sprinkled in like seasoning on a well-prepared meal, but Scripture was never at the heart of the argument.

As Protestants embraced “sola scriptura” (by Scripture alone), Catholics prided themselves on teachings that were based on both faith and reason. The church’s teachings were heavily dependent on Aristotelian philosophy as interpreted by scholastic philosophers and theologians. Scripture served as “proof texts” to foregone conclusions.

Catholics were expected to accept this teaching on papal authority. Others were expected to be convinced by the clarity of the argument.

The advantage of appealing to reason, not faith, was that it allowed the church to engage in dialogue with secular thinkers. The disadvantage was that it was dry and uninspiring. It also made it difficult for Protestants to appreciate Catholic social teaching.

“Dilexi te” (“I have loved you”), the new apostolic exhortation issued Oct. 4 by Pope Leo XIV, is different. This is a document addressed to Christians and it is steeped in Scripture.

Leo inherited what would become his first apostolic exhortation from Pope Francis, whose views he embraced while revising it to reflect his thoughts. But both pontiffs felt that those who did not see care for the poor as “the burning heart of the Church’s mission … need to go back and re-read the Gospel.”

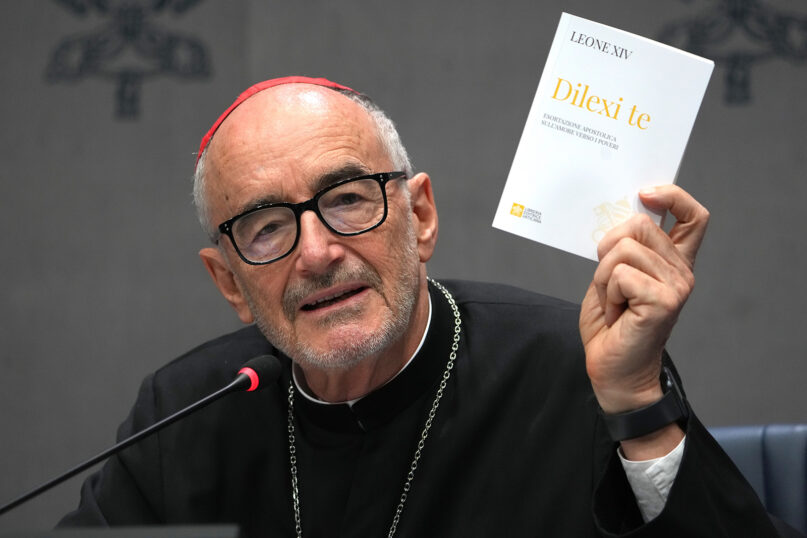

Cardinal Michael Czerny attends a press conference at the Vatican to present Pope Leo XIV’s exhortation “Dilexi te” about love for the poor, Oct. 9, 2025. (AP Photo/Domenico Stinellis)

The first two chapters of “Dilexi te” provide wonderful scriptural passages for preaching and reflection on the proper relationship between Christians and the poor. And since all Christians share the same Scriptures, the chapters also provide rich material for ecumenical dialogue among Christians on how we should think about and act toward the poor. It is not till Chapter 4 that the document delves into Catholic social teaching.

Chapters 1 and 2 of “Dilexi te” teach that “Love for the Lord, then, is one with love for the poor,” or as the Gospel of Matthew puts it, “Just as you did it to one of the least of these brothers and sisters of mine, you did it to me.” Chapter 3 looks at teachings of the fathers of the church and the role of religious communities in caring for the poor.

Chapter 2 is a cornucopia of biblical quotes, reviewing biblical teaching about God’s concern for the poor and our obligation to love and care for them. The document’s fundamentally scriptural argument is that “contact with those who are lowly and powerless is a fundamental way of encountering the Lord of history.” The Gospels make clear that through the incarnation, Leo argues, God chose “to share the limitations and fragility of our human nature, he himself became poor and was born in the flesh like us.”

Later in the chapter Leo says, “Wanting to inaugurate a kingdom of justice, fraternity and solidarity, God has a special place in his heart for those who are discriminated against and oppressed, and he asks us, his Church, to make a decisive and radical choice in favor of the weakest.”

“The Gospel shows us that poverty marked every aspect of Jesus’ life,” says the apostolic exhortation, from his birth in Bethlehem to his death on the cross. Jesus “presented himself to the world not only as a poor Messiah, but also as the Messiah of and for the poor.”

Christ is present in the poor, and his message was one of liberation for the poor, Leo says. In Jesus’ first words at the beginning of his public ministry he echoed the Hebrew Prophet Isaiah, as Luke’s Gospel says: “The Spirit of the Lord is upon me, because he has anointed me to bring good news to the poor.” His miracles, Leo’s exhortation says, “are manifestations of the love and compassion with which God looks upon the sick, the poor and sinners who, because of their condition, were marginalized by society and even people of faith.”

The message the pope wants to convey is that “God is near, God loves you.” He quotes from the Beatitudes: “Blessed are you poor, for yours is the kingdom of God.” As a result, “Christ’s Church, must be a Church of the Beatitudes, one that makes room for the little ones and walks poor with the poor, a place where the poor have a privileged place,” Leo writes.

To challenge those who see the poor as sinners or deserving of what they get, Jesus tells the parable of the rich man, who is stunned to see Lazarus, the beggar outside his door, in heaven, while the rich man is denied. God says to the rich man, “Child, remember that during your lifetime you received your good things, and Lazarus in like manner evil things; but now he is comforted here, and you are in agony.”

It is clear that Leo and Francis believe that “our faith in Christ, who became poor, and was always close to the poor and the outcast, is the basis of our concern for the integral development of society’s most neglected members.”

Leo wonders, “even though the teaching of Sacred Scripture is so clear about the poor, why many people continue to think that they can safely disregard the poor.”

Chapter 2 cites Christ’s second commandment, “You shall love your neighbor as yourself,” as well as St. John’s first letter: “Those who do not love a brother or sister whom they have seen, cannot love God whom they have not seen.”

Quoting Francis, Leo warns against watering down these texts through overly spiritual interpretations. The message of God’s word is “so clear and direct, so simple and eloquent, that no ecclesial interpretation has the right to relativize it. The Church’s reflection on these texts ought not to obscure or weaken their force, but urge us to accept their exhortations with courage and zeal.”