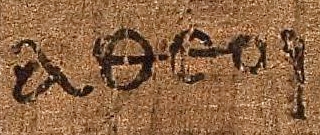

![The Greek word "atheoi" αθεοι ("[those who are] without god") as it appears in the Epistle to the Ephesians 2:12, on the early 3rd-century Papyrus 46.](https://religionnews.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/atheos.jpg)

The Greek word “atheoi” αθεοι (“[those who are] without god”) as it appears in the Epistle to the Ephesians 2:12, on the early 3rd-century Papyrus 46.

Rush Limbaugh casts the blame on Mainline Protestantism for selling its birthright for a mess of LGBT pottage. Bill O’Reilly points the finger at rap music and “pernicious entertainment.” Whatever.

Meanwhile, Ross Douthat spins a new version of the old story that, actually, a lot of Nones still do religious things and that young folks, aka Millennials, may come back to church when they grow up the way their forebears did. Rod Dreher joins Russell Moore in looking for a leaner, cleaner Christianity. And over at GetReligion, Terry Mattingly laments the lack of a term for the opposite of Nones, suggesting (without a lot of conviction) “convictionals.”

So who are these Nones of which we speak?

They’re the people who when you ask them what their religion is, they say, “None.” That doesn’t necessarily mean they disbelieve in God, or that they don’t say prayers, or even that they don’t attend a house of worship. What they’re doing is answering a question about personal identity, as in: What is your nationality? Or, what is your race? Or, what is your sexual preference? Nones are the people who choose not to make a religion part of their identity. That’s why the true opposite of “None” is “Religious.”

Now, there are two ways that you can come to have a religious identity: by ascription or by choice. You can become a Jew, for example, by being born to a Jewish mother (ascription) or by converting to Judaism (choice). Most religious traditions provide for both ways, though to varying degrees. While Baptists restrict church membership to those who make a choice for Christ by having themselves baptized, the fact is that unbaptized children who grow up in Baptist families come to think of themselves as Baptists, and in due course are more likely than anyone else to make the choice to become a Baptist.

The reason that the percentage of Nones has risen as steeply as it has — more than 300 percent in the past quarter century, to 22.8 percent of all American adults, according to Pew — is that since 1990 we have come to understand the question of religious identity as being more about choice than ascription. Thirty years ago, someone who was sent to a Presbyterian Sunday School as a child but who has not darkened a church door in years could well have answered the “what is your religion” question with “Presbyterian.” Now, she is more likely to say, “None.”

What this means is that today, a shrinking proportion of Americans are “nominal” religious identifiers in the strict sense of the word “nominal”: They’re less likely to identify themselves with the name of the religious tradition they were raised in if their only current connection to the tradition is that they happened to be raised in it. That explains why religious belief and behavior have declined far less than the percentage of Nones has risen — about 50 percent less, by my calculation.

Not that the decline hasn’t been significant. Indeed, as Pew shows, the proportion of self-described unbelievers — atheists and agnostics — is on the rise. But the reinscription of nominal religious identifiers as Nones doesn’t do anything to change the actual belief and practice of religion in America. It only changes our perception of the country’s religious layout.