The Rev. Jeannie Smalls cries during a prayer vigil at Morris Brown AME Church in Charleston, S.C., on Thursday (June 18, 2015). A white man suspected of killing nine people in a Bible study group at a historic African-American church in Charleston was arrested Thursday and U.S. officials are investigating the attack as a hate crime. Photo courtesy of REUTERS/Grace Beahm/Pool

(RNS) For many, the massacre at a black church in Charleston, S.C., is simply another mass shooting.

But for African-Americans, church violence has historic dimensions.

The attack Wednesday (June 17) at Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church reflects “a pattern of random, racialized violence against religious institutions,” said Valerie Cooper, associate professor of black church studies at Duke University.

“Persons burned churches because they thought the congregating of blacks together meant that that was a foment for some kind of revolutionary action,” said the Rev. Teresa Fry Brown, historiographer of the African Methodist Episcopal Church and a black church expert at Emory University’s Candler School of Theology.

Here are some examples of black church violence over the years:

1. The Charleston, S.C., church was torched centuries ago.

It burned in the 1800s during a controversy surrounding Denmark Vesey, one of the church’s organizers, who was the leader of a major slave rebellion in that city.

“Worship services continued after the church was rebuilt until 1834 when all black churches were outlawed,” the church’s website notes. “The congregation continued the tradition of the African church by worshipping underground until 1865 when it was formally reorganized, and the name Emanuel was adopted, meaning ‘God with us.’”

2. The 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Ala., was bombed in 1963.

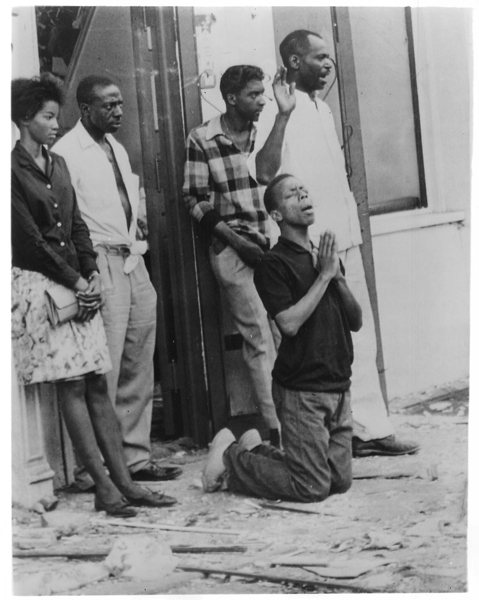

(1963) A man falls to his knees in prayer amid shattered glass from windows of the 16th Street Baptist Church and surrounding buildings in Birmingham, Ala. Four young girls died as a racist’s bomb exploded at 10:22 a.m. on Sept. 15 during worship services and Sunday school sessions. In the following outbreak of violence throughout the area, two young black men were shot to death. Pleas to stop further bloodshed were issued from government, civil rights and religious leaders across the nation. Religion News Service file photo

Four girls who were in the church perished on Sept. 15, 1963.

“Those little girls were there for Sunday school,” said Cooper. “There were four people killed but there were lots of other people maimed. One little girl lost an eye, for example. There are people, in other words, still walking around with the scars of that bombing.”

The church was a key meeting place of civil rights leaders who were planning voter registration and other activities.

“It was timed to go off so when the most number of people would be there,” said Fry Brown.

3. The Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.’s mother was killed in church.

Alberta Williams King died on June 30, 1974, just after playing “The Lord’s Prayer” at Atlanta’s Ebenezer Baptist Church. Her son was assassinated six years earlier.

“She was killed playing the organ on Sunday morning,” said Fry Brown.

4. There was a spate of black church arsons in the South in the 1990s.

The Center for Democratic Renewal recorded 73 black churches that were burned, firebombed or vandalized between January 1990 and April 1996. President Clinton created the National Church Arson Task Force, which reported on arsons at churches black and white, small and large, but made particular note in 1998 of the effect of the fires on African-American congregations.

“When actual or perceived racial hatred has sparked the arson of a church, the crime is even more egregious. In the African American community, the church historically has been a primary community institution,” the Justice Department task force’s report reads. “So, for the African American community, it was decidedly disturbing to see the number of churches being burned.”

5. Black church arsons took place in the north, too.

Hours after the 2008 election of President Obama, Macedonia Church of God in Christ in Springfield, Mass., burned.

Two of the three co-defendants admitted that they doused the partially built church with gas and set it afire to denounce the election of the nation’s first black president.

“My faith sustained me to declare that we would rebuild. The thought never came that we would abandon this project,” said Bishop Bryant Robinson Jr., pastor of the church, when it was dedicated in 2011, a newspaper reported. “We were delayed, but not denied.”

YS/MG END BANKS