(RNS) — I don’t know about you, but these days I’m awash with anxiety. Hyperpartisan politics, raising a teenager … it all contributes to an ongoing sense of waiting for the other shoe to drop.

But faith, as Richard Rohr reminds us, is a relationship of trust between human beings and God, and when I allow anxiety to take the driver’s seat, I am not practicing faith but something else.

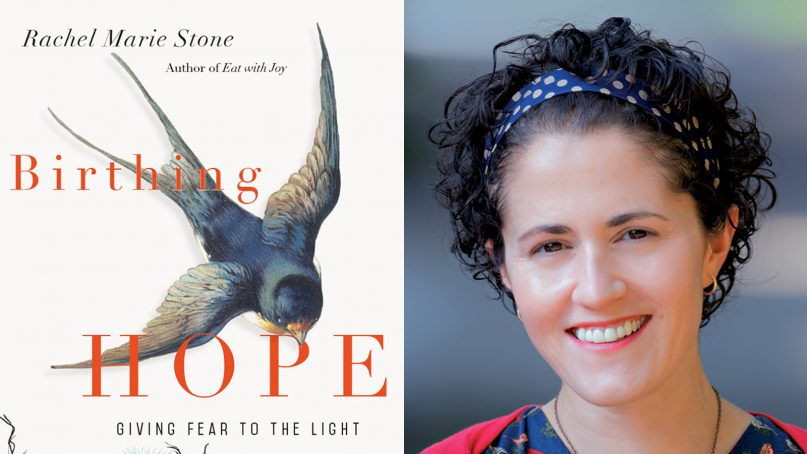

So I was particularly interested in reading Rachel Marie Stone’s new memoir, “Birthing Hope: Giving Fear to the Light.” I resonated with a lot of her experiences. How, in an age of anxiety, do we surrender fear to the light?

Religion News Service interviewed Stone about her book. Her responses follow.

RNS: I’m struck by the way your book covers so many themes: anxiety, birth, embodiment, loss. How would you describe it in an elevator pitch?

Rachel Marie Stone: Very briefly, I would sketch it as a memoir of anxiety. It’s also a memoir of living through hard times. And it’s also a memoir of motherhood and hope, or motherhood and fear. But it’s not only a book for mothers.

RNS: You have been dealing with anxiety ever since you were a child. How did that begin?

Stone: I had a lot of big fears I didn’t talk about. Any time my parents would be even five minutes late, I worried so much.

“Birthing Hope: Giving Fear to the Light” by Rachel Marie Stone. Image courtesy of InterVarsity Press

Weirdly, one of my earliest anxieties was that I was very worried about another Holocaust. My mother is Jewish, so I probably knew too much about the Holocaust of WWII when I was really young. I was thinking that there must be something wrong with us Jews that would make people want to get rid of us throughout history.

Also, I was a bit of a hypochondriac. I would notice something on my body and quietly convince myself that it was cancer and that I was going to die. Or I had touched something on the bus that was going to give me AIDS. AIDS is actually a big part of the book. Other people my age have no memory of growing up with a worry about AIDS, but in New York City in 1986, when I was in kindergarten, people would play tag but would tag you with AIDS. And there was a guy in our church, a friend of my dad’s, who died of AIDS.

RNS: How have you coped with anxiety as an adult?

Stone: I’m not taking any anxiety medication now, but I have in the past and it has been very helpful. It’s a really helpful tool for people with anxiety disorders. But I feel like it would be irresponsible for me not to say that they can be habit-forming and they are very powerful substances. Also, they don’t resolve your narrative problem. In people with anxiety, it’s often a story that needs shifting, maybe even more than brain chemicals. The brain chemistry is absolutely real, but there’s reason to be cautious about powerful drugs that doctors prescribe so easily.

What has worked for me are therapy, meditation, breathing and yoga — and changing the narrative.

I’ll give an example that may sound stupid to some people but is real. My cat that I adored just died last month at age 15. Because I do this anxiety thing and worry about things that haven’t happened yet, I told myself long ago that I would absolutely fall apart when he died. That was the story that I imagined. I spent so much time imagining a tragic end, but when the moment came and it was clear that he had reached the end, it was tempting to freak out, but I realized that would make his death all about me. Even the narrative of “I can’t live without him” is still about me and my feelings. There was a lot of comfort in focusing on what I did have then, which was having him still alive. I could give him a death and a good burial, and be faithful to what I needed to do. That’s not to say I wasn’t sad, but often the things that bring us suffering are wrong narratives that we cling to but don’t really serve us.

RNS: I’d like to know how your faith helps you with anxiety, or if it does. But first, tell me about your religious background, because you are Jewish and also writing a Christian book for a Christian publishing house (InterVarsity Press).

Author Rachel Marie Stone. Photo courtesy of InterVarsity Press

Stone: My mom converted to evangelical Christianity before I was born. This is always contentious, because some Jews wouldn’t consider me a Jew, but according to the Talmud, a Jew that’s born a Jew can never not be a Jew. Culturally, it’s impossible for me to think of myself and my mother as anything but Jewish. But the Christian narrative is the one I was raised in and continue to live into. I worship at an Episcopal church now and follow the rhythm of the liturgical year.

RNS: How does your faith figure into living with anxiety?

Stone: I think a lot of the quirks of the specific religious tradition that I was raised in actually made anxiety worse, because in that scenario, God and/or Jesus were always evaluating everything I did or even thought. There was encouragement to remember that “Jesus is always watching you!” Kind of like Jesus was a scary Santa Claus who sees you when you’re sleeping.

Also, even the way that evangelicals will often pray can produce anxiety, like, “Fix this thing, God; fix me; take this bad thing away.” Evangelicals talk about prayer as if it’s all about fixing the bad things. There’s often a subtle or not-subtle implication that if you pray hard enough and believe hard enough, that it’s going to get fixed. That there will be a miracle. I guess that’s comforting for some, but it’s anxiety-producing for others to think that if they just work and pray a little harder, they can fix it.

It feeds into an idea that many people with anxiety already live with: that the act of worrying itself is necessary in order to prevent bad things: “If I worry hard enough about this now, it won’t happen later.” Worrying is almost a protective impulse, like you are inoculating yourself against the pain of it actually happening. But the truth is that we’re almost never prepared for the actual bad things that come out of the blue. What do people say about bad things that happen? They say, “We never saw it coming” or “We never thought it would happen to us.” You can’t prevent it or even alleviate it by thinking your way out of it beforehand.

RNS: What else helps you?

Stone: I have taken a lot of comfort lately from a book that’s co-written by Archbishop Desmond Tutu and the Dalai Lama, called “The Book of Joy.” It’s a great resource for those who suffer in their thinking, or are curious about meditation and what Buddhism might offer. It’s a lot about shifting the narrative. So much of getting well, or even living well with anxiety, is shifting the way we tell the story, and also shifting our attention and compassion to others. That can help so, so much.

RNS: What are you hoping readers will take from the book?

Stone: A sense of wonder and respect for what humans are — and what humans can endure. Not because of what I’ve lived through, but because I point to stories and experiences that reveal something essential about existence. I think that essential thing, which we are very good at avoiding in North American culture, is the reality that joy and suffering always go together. We don’t get to the triumphal, glorious moments in life without struggling for them. That’s why I use the metaphor of birth. When a baby takes her first breath, it’s amazingly wonderful. But it took blood and tears and sacrifice to get there.

(The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily represent those of Religion News Service.)